Banff Springs snail facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Banff Springs snail |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Physella johnsoni | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Subclass: | Heterobranchia |

| Clade: | Euthyneura |

| Superorder: | Hygrophila |

| Family: | Physidae |

| Genus: | Physella |

| Species: |

P. johnsoni

|

| Binomial name | |

| Physella johnsoni (Clench, 1926)

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Banff Springs snail (Physella johnsoni) is a tiny, air-breathing freshwater snail. It belongs to a family of snails called Physidae. Scientists believe this snail became its own species about 10,000 years ago. It split off from a similar snail called Physella gyrina.

Contents

Meet the Banff Springs Snail

These tiny water animals are a type of mollusc, like clams or octopuses. They are about the size of a small corn kernel. The biggest ones are only about one centimeter long. Like all snails in the Physidae family, their shells are "sinistral." This means the shell coils to the left when you hold the snail with its opening facing you. The snails eat periphyton, which is a mix of algae and tiny organisms that grow on surfaces in the water.

The Banff Springs snail was first found in 1926. It lives in nine special hot springs on Sulphur Mountain in Banff National Park, Alberta, Canada. You won't find it anywhere else in the world! These snails are very unique because they can live in hot spring water. This water has very little oxygen and a lot of hydrogen sulfide, which is a gas that smells like rotten eggs. Most animals cannot survive in such a harsh environment. Since it was discovered, the snail's home has shrunk. It now lives in only five of the original nine hot springs.

Protecting the Banff Springs Snail

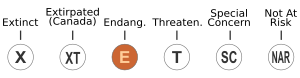

The number of Banff Springs snails and their living areas have shrunk. This is likely because people use the hot springs. Changes in water temperature also play a role. In April 1997, it became the first living mollusc to be put on Canada's national list of species at risk. In 2000, COSEWIC (a group that assesses wildlife in Canada) said it was endangered. The Canadian Species at Risk Act also listed it as endangered in Canada.

Parks Canada is working hard to protect these snails. They are doing this through education, enforcing rules, closing some facilities, and doing scientific research. In 1996, Parks Canada started a special program to help the snail. This included closing the swimming pool at the Cave and Basin National Historic Site. The program aims to keep snail populations healthy. They also want to bring snails back to all the places they used to live. Hopefully, this will help the snail's status improve.

Snail Population Changes

The number of snails changes throughout the year. When there are very few snails, they are most at risk. Human actions or natural events, like a spring drying up, can harm them. Scientists don't know exactly why the population changes so much. It is probably due to shifts in water temperature and chemistry. Changes in the bacteria and algae they eat might also be a reason. It is estimated that the population goes from about 1,500 to 15,000 snails. When numbers are lowest, all the snails could fit in an ice cream cone. When numbers are highest, they could fill a one-litre milk carton.

Conservation biologist Dwayne Lepitzki thinks that climate change is causing the hot springs to dry up more often. This also affects the snail population. Before 1996, the Upper Hot Spring dried up only once, in 1923. Now, it happens regularly.

Research and Recovery Efforts

Every four weeks, researchers and volunteers count the snails. They also test the water's chemistry. There is also a program to breed snails in captivity. If this program works, the snails will be put back into two more springs where they used to live. Baby snails are currently hatching in captivity. It takes about four to eight days for the eggs to hatch.

Snails were once gone from the Upper Hot, Upper Middle, Kidney, and Vermilion Cool springs. However, thanks to Parks Canada's recovery efforts, they are now back in the Upper Middle (since 2002) and Kidney springs (since 2003). The largest number of snails can be found at the Cave and Basin National Historic Site.