Battle of Aljubarrota facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Aljubarrota |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Portuguese Crisis of 1383–85 | |||||||

Illustration of the Battle of Aljubarrota by Jean de Wavrin |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Supported by: |

Supported by: Italian allies |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

About 6,600 men:

|

About 31,000 men:

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Fewer than 1,000 | 4,000–5,000 5,000 in the aftermath |

||||||

The Battle of Aljubarrota was a very important fight between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Crown of Castile. It happened on August 14, 1385. The battle took place near Aljubarrota, in central Portugal.

The Portuguese army was led by King John I of Portugal and his great general Nuno Álvares Pereira. They also had help from English allies. The Castilian army was much larger and led by King John I of Castile. They had allies from Aragon, Italy, and France.

Portugal won a huge victory. This win stopped Castile from taking over the Portuguese throne. It also ended a difficult time in Portugal's history, known as the 1383–85 Crisis. The battle made sure John I became the true King of Portugal. It also confirmed Portugal's independence and started a new royal family, the House of Aviz.

Even after the battle, there were small fights with Castilian troops until 1390. But these fights did not threaten Portugal's new king or its independence.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened: The Road to Aljubarrota

The late 1300s were a tough time in Europe. There was the Hundred Years' War between England and France. The Black Death (a terrible plague) was also sweeping across the continent. Portugal faced its own problems.

A King Dies Without an Heir

In October 1383, King Ferdinand I of Portugal died. He had no sons to take his place. His only child was a daughter, Princess Beatrice of Portugal. Before he died, King Ferdinand had signed a deal called the Treaty of Salvaterra de Magos. This treaty said that Princess Beatrice would marry King Juan I of Castile. It also meant that the crown of Portugal would go to their children.

Most Portuguese people were not happy about this. The nobles did not want Portugal to become part of Castile. Merchants in Lisbon, the capital city, were also angry because they were left out of the talks. With no clear leader, Portugal had no king from 1383 to 1385. This period is called the 1383–85 Crisis.

A New Leader Rises

In December 1383, John, the Grand Master of the Aviz Order, took action. He was a natural son of a previous king, Peter I of Portugal. He became a leader for those who wanted Portugal to stay independent. The Lisbon merchants named him "rector and defender of the realm."

King Juan I of Castile still wanted the Portuguese throne for himself and his wife, Beatrice. He tried to take control. But in April 1384, a smaller Portuguese army led by Nuno Álvares Pereira defeated a Castilian force at the Battle of Atoleiros. The Portuguese used a clever tactic, forming a strong infantry square to push back cavalry. They won without losing any soldiers.

Later, King Juan I of Castile led a larger army to attack Lisbon. They surrounded the city for four months. But they had to leave because they ran out of food and the plague spread among their soldiers. Nuno Álvares Pereira's constant attacks also made it hard for them.

John Becomes King

To make his claim stronger, John of Aviz worked hard in politics and talked with England. On April 6, 1385, a special council in Coimbra declared him King John I of Portugal. After becoming king, John I took control of cities that supported Castile.

King Juan I of Castile was very angry about this "rebellion." In May, he sent a huge army of 31,000 men to invade Portugal. A smaller force in the north was defeated by Portuguese nobles. When King John I of Portugal heard about the invasion, he met with Nuno Álvares Pereira. They decided to fight the Castilians before they could reach Lisbon again.

Around Easter 1385, mercenaries arrived from Gascony. These were about 200 English longbowmen, who were experienced fighters. They came to help Portugal because of an old agreement called the Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1373. This treaty is still the oldest active international treaty today!

The Portuguese army marched to stop the Castilians near Leiria. Nuno Álvares Pereira chose the perfect spot for the battle: São Jorge, near Aljubarrota. It was a small, flat hill surrounded by streams. This location was great for their defensive plan. By choosing this spot, John I of Portugal forced the Castilian king to fight on his terms, rather than letting him besiege Lisbon.

Setting the Stage: Portuguese Preparations

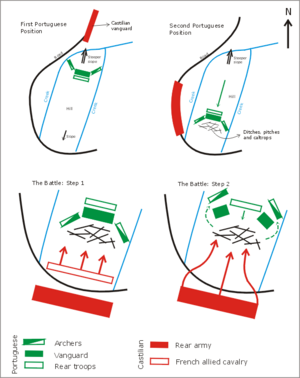

On the morning of August 14, around 10 o'clock, the Portuguese army took its position. They were on the north side of the hill, waiting for the Castilians. The Portuguese soldiers were set up like this: dismounted cavalry and foot soldiers in the middle, with archers on the sides.

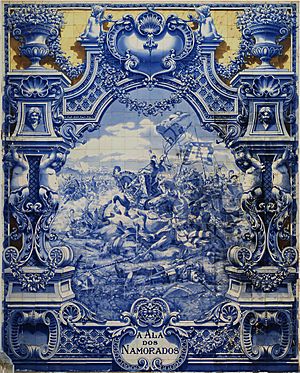

A special group of about 200 young unmarried nobles formed the "Ala dos Namorados" (Lovers' Flank) on the left side. The right side was called the "Ala de Madressilva" (Honeysuckle Flank). Natural barriers like streams and steep slopes protected both sides of the army. King John I of Portugal himself commanded the reserve troops at the back.

The Portuguese were on high ground, so they could see the enemy coming. Their front was protected by a steep slope. The back of their position, which would become their main front, was at the top of a narrow slope. This area was also defended by trenches and sharp spikes called caltrops. These traps were designed to stop enemy cavalry.

Some people thought the Portuguese soldiers were poorly equipped. However, there is no strong evidence for this. While some sources say their armor was not perfect, it was likely good enough for infantry soldiers. Many Portuguese soldiers had helmets, padded armor, and mail shirts. They used spears, axes, and pollaxes (a type of pole weapon).

Castilian Arrival and Portuguese Adjustments

The Castilian army arrived from the north around midday. King John of Castile saw how strong the Portuguese position was. He decided not to attack head-on. Instead, his huge army, about 31,000 men, slowly moved around the hill. Castilian scouts had found that the south side of the hill had a gentler slope, and that is where King John of Castile wanted to attack.

The Portuguese army quickly reacted. They turned around and moved to the south slope of the hill. Since they were fewer and had less ground to cover, they got into position quickly. To make their defense even stronger, General Nuno Álvares Pereira ordered his men to dig ditches, pits, and place caltrops. This tactic was very good against cavalry, which was a strength of the Castilian and French armies.

Around six o'clock in the afternoon, the Castilian army was ready to fight. King John of Castile later reported that his soldiers were very tired from marching all morning under the hot August sun. But there was no time to rest; the battle was about to begin.

The Battle Begins

The Castilians started the battle. Their French allies, who were heavy cavalry, charged first. They wanted to break the Portuguese lines. There were about two thousand French knights. They formed up tightly and charged forward.

However, this charge was a disaster for the French. They were too far ahead of the main Castilian army. They had to charge uphill, through obstacles, and into a narrow passage. A storm of arrows and crossbow bolts hit them, killing many horses and injuring men. This caused a lot of confusion. Even though the French knights were heavily armored, their attack failed. Many were killed or captured. The rest of the Castilian army was slow to help them.

Some accounts say the Spanish Castilians did not rush to help the French. They thought the French were too boastful and wanted them to tire themselves out. This made King John of Castile very upset.

The Main Fight

When the main Castilian force finally attacked, they looked very impressive because of their numbers and equipment. But as they tried to reach the Portuguese line, they became disorganized. They were squeezed into the narrow space between the two streams that protected the Portuguese flanks.

The Portuguese quickly reorganized. Nuno Álvares Pereira's front line split into two. King John I of Portugal ordered his archers and crossbowmen to pull back. His reserve troops then moved forward into the gap. With all his soldiers needed at the front, there was no one to guard the captured French knights. So, King John ordered them to be killed.

The Castilians had to fight uphill with the sun in their eyes. They were trapped between the Portuguese defenses and their own advancing troops. English longbowmen shot arrows from behind the Portuguese line, and crossbowmen shot from the sides. Castilian knights had to get off their horses and break their long lances to fight in the crowded battle.

Both sides suffered heavy losses. The "Ala dos Namorados" (Lovers' Flank) became famous for holding off the heavily armored Castilian knights who tried to attack the Portuguese from the sides.

Castilian Retreat

By sunset, only an hour after the battle began, the Castilian position was hopeless. When the Castilian royal flag-bearer fell, the soldiers in the back thought their king was dead. They panicked and started to run away. Soon, the entire Castilian army was fleeing. King Juan of Castile had to escape quickly to save his own life, leaving behind many soldiers and nobles.

The Portuguese chased them down the hill. With the battle won, they killed many more Castilians before it got too dark to see. King John I of Portugal was described as a tall and strong leader. He fought bravely with his pollaxe, knocking down many enemies.

Aftermath: The Impact of Victory

During the night and the next day, about 5,000 more Castilians were killed by people from the nearby villages. A famous Portuguese legend tells of a woman named Brites de Almeida, known as the Padeira de Aljubarrota (the baker-woman of Aljubarrota). She was said to be very tall and strong, with six fingers on each hand. The story says she killed seven Castilian soldiers hiding in her bakery after the battle! While this specific story might be a legend, it is true that local people often attacked defeated enemies during this time.

The next morning, the true scale of the battle became clear. So many Castilian bodies were on the field that they blocked the streams around the hill. King John I of Portugal offered the surviving enemies a chance to go home safely. Many important Castilian nobles died that day, and entire army groups were wiped out. Castile declared a period of mourning that lasted until Christmas 1387.

In October 1385, Nuno Álvares Pereira led another attack into Castilian land. He defeated an even larger Castilian army at the Battle of Valverde. Small fights continued for five more years until King John I of Castile died in 1390. But these fights did not threaten Portugal's independence. Castile finally recognized Portugal's independence in 1411 with the Treaty of Ayllón.

The victory at Aljubarrota made John of Aviz the undisputed King of Portugal. It also established the House of Aviz as the new royal family. In 1386, Portugal and England formed a strong, lasting friendship with the Treaty of Windsor. This treaty is still active today, making it the oldest alliance in the world!

John's marriage to Philippa of Lancaster in 1387 started the second Portuguese royal family. Their children became very important figures in history. Their son Duarte, or Edward of Portugal, became a king known for his wisdom. Another son, Prince Henrique, or Henry the Navigator, helped start Portugal's famous sea explorations to Africa.

To celebrate his victory and thank God, King John I of Portugal ordered the building of the Santa Maria da Vitória na Batalha monastery. He also founded the town of Batalha near the battle site. This monastery is a beautiful example of Late Gothic and Manueline style architecture. The king, his wife, and several of his children are buried there.

In 1393, a chapel was built where Nuno Álvares Pereira's flag stood during the battle. This helps us know the exact location of the fight. In 1958, archaeologists began digging at the site. They found a complex system of about 800 pits and many defensive ditches. This makes Aljubarrota one of the best-preserved battlefields from the time of the Hundred Years' War.

In 2002, the Battle of Aljubarrota Foundation was created. They worked to restore the battlefield. In 2008, they opened a modern Interpretation Center of the Battle of Aljubarrota. In 2010, the battlefield was officially recognized as a "National Monument" in Portugal.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Aljubarrota para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Aljubarrota para niños