Battle of Fort Dearborn facts for kids

The Battle of Fort Dearborn was a fight between United States troops and Potawatomi Native Americans. It happened on August 15, 1812, near Fort Dearborn in what is now Chicago, Illinois. At that time, the area was a wilderness. This battle was part of the War of 1812, a conflict between the United States and Great Britain, which also involved Native American tribes.

The battle took place after the fort was ordered to be emptied by the American army commander, William Hull. The fight lasted only about 15 minutes. The Potawatomi won completely, and Fort Dearborn was burned down afterward. Some of the soldiers and settlers who were captured were later set free after a payment was made. After this battle, the U.S. government decided that Native Americans needed to be moved away from areas where settlers lived. Fort Dearborn was rebuilt in 1816.

Quick facts for kids Battle of Fort Dearborn |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

The Battle of Fort Dearborn is remembered with Defense, a 1928 sculpture by Henry Hering on the DuSable Bridge in Chicago. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Potawatomi | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Chief Blackbird | Capt. Nathan Heald (WIA) Capt. William Wells † |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 400–500 | 66 military + 27 dependents | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 15 | Military 38 killed 28 captured Civilian 14 killed 13 captured |

||||||

Contents

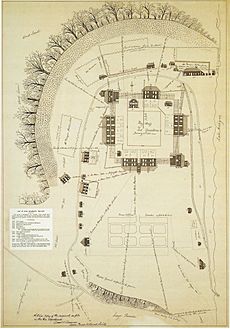

Building Fort Dearborn

Fort Dearborn was built by U.S. troops in 1803. It was led by Captain John Whistler. The fort was located on the south bank of the Chicago River. Today, this area is part of downtown Chicago. At the time, it was considered a very remote wilderness. The fort was named after Henry Dearborn, who was the U.S. Secretary of War.

The fort was built after the Northwest Indian War (1785–1795). This war ended with the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. As part of this treaty, a group of Native American tribes gave up large parts of modern-day Ohio to the United States. They also gave up other lands, including an area around the mouth of the Chicago River.

Tensions Rise

The British Empire had given the Northwest Territory to the United States in 1783. This territory included what are now the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and parts of Minnesota. However, Native American nations and the U.S. disagreed over this land.

Native American leaders like Tenskwatawa and his brother Tecumseh formed a group of tribes. They wanted to stop American settlers from moving onto their lands. The British saw these Native American nations as important friends. They also saw them as a way to protect their Canadian colonies. So, the British gave weapons to the Native Americans. Attacks on American settlers in the Northwest made the relationship between Britain and the U.S. even worse.

In 1810, Captain Nathan Heald took over command of Fort Dearborn. He was not happy with his new job. Heald married Rebekah Wells in Kentucky and they moved to the fort in June 1811.

As the United States and Britain got closer to war, feelings between settlers and Native Americans near Fort Dearborn grew more hostile. In 1811, British messengers tried to get Native Americans in the area to support them. They said Britain would help them fight against American settlement. On April 6, 1812, some Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) Native Americans killed two men near the Chicago River. After this, some settlers moved into Fort Dearborn for safety. Captain Heald organized 15 civilian men into a local defense group.

The Battle Begins

On June 18, 1812, the United States declared war on the British Empire. On July 17, British forces captured Fort Mackinac. General William Hull learned about this on July 29. He immediately ordered Captain Heald to leave Fort Dearborn. Hull was worried the fort could not get enough supplies.

Hull's orders reached Fort Dearborn on August 9. He told Heald to destroy all weapons and ammunition. He also said to give any remaining goods to friendly Native Americans. This was to get an escort to Fort Wayne. Hull also sent a copy of these orders to Fort Wayne. He asked them to help Heald. Captain William Wells, who was Heald's wife's uncle, gathered about 30 Miami Native Americans. Wells and the Miamis traveled to Fort Dearborn to help escort the people leaving.

Wells arrived at Fort Dearborn around August 12 or 13. On August 14, Heald met with Potawatomi leaders. He told them he planned to leave the fort. The Native Americans thought Heald would give them weapons, ammunition, food, and whiskey. They also believed he would pay them a lot of money if they escorted them safely to Fort Wayne. However, Heald ordered all extra weapons, ammunition, and liquor destroyed. He feared the Native Americans would misuse them. On August 14, a Potawatomi chief named Black Partridge warned Heald. He said the young men of his tribe planned to attack. He could no longer control them.

At 9:00 am on August 15, the group left Fort Dearborn. It included 54 U.S. soldiers, 12 local fighters, nine women, and 18 children. They planned to march to Fort Wayne. Wells led the group with some Miami escorts. The rest of the Miamis were at the back. About 1.5 miles (2.4 km) south of Fort Dearborn, a group of Potawatomi warriors attacked them. Heald reported that when they saw the Native Americans preparing to ambush them, the company marched to the top of a sand dune. They fired their guns and charged at the attackers.

This move separated the soldiers from the wagons. The large Native American force quickly moved into the gap. They divided and surrounded both groups. During the fight, some Native Americans attacked the wagons. These wagons held the women, children, and supplies. Local fighters, Ensign Ronan, and the fort doctor Van Voorhis defended the wagons. These officers and local fighters were killed. Two women and most of the children also died. Wells tried to help those at the wagons. He was brought down and killed. Eyewitnesses said he fought off many Native Americans before he died.

The battle lasted about 15 minutes. After this, Heald and the surviving soldiers went to a higher area on the prairie. They surrendered to the Native Americans. They were taken as prisoners to a camp near Fort Dearborn. Heald reported that 26 soldiers, all 12 local fighters, two women, and twelve children were killed. The other 28 soldiers, seven women, and six children were taken prisoner. Some survivors said the Miami warriors fought for the Americans. Others said they did not fight at all.

After the Battle

After the battle, the Native Americans took their prisoners to their camp. Fort Dearborn was burned to the ground. The area remained empty of U.S. citizens until after the war ended. Some prisoners died while captured. Others were later set free after a payment. The fort was rebuilt in 1816.

General William Henry Harrison, who was not at the battle, later said the Miami had fought against the Americans. He used the Battle of Fort Dearborn as a reason to attack Miami villages. Because of this, Miami Chief Pacanne and his nephew Jean Baptiste Richardville stopped being neutral in the War of 1812. They became allies with the British.

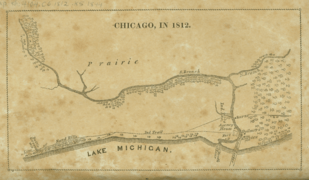

Where the Battle Happened

People who saw the battle said it happened on the lake shore. This was about 1 to 2 miles (1.6 to 3.2 km) south of Fort Dearborn. Heald's official report said it was 1.5 miles (2.4 km) south. This would place the battle near where Roosevelt Road and Michigan Avenue are today.

A survivor named Juliette Kinzie said before she died in 1870 that the battle started near a large cottonwood tree. This tree was on 18th Street between Prairie Avenue and the lake. It was thought to be the last tree from a group that were small trees during the battle.

This tree fell in a storm on May 16, 1894. Part of its trunk was saved at the Chicago History Museum. However, some historians say that the stories about this tree came from people who moved to Chicago much later. Also, based on the size of the saved tree trunk, it was probably not old enough to have been there during the battle. Still, the area at 18th Street and Prairie Avenue is known as the battle site. In 2009, a park called "Battle of Fort Dearborn Park" was dedicated near this spot.

Monuments

In 1893, George Pullman had a sculpture made by Carl Rohl-Smith. It showed the rescue of Margaret Helm by Potawatomi chief Black Partridge. He led her and others to Lake Michigan and helped her escape by boat. This monument was moved to the Chicago History Museum in 1931.

In the 1970s, Native American groups protested the monument. They felt it was offensive, so it was removed. In the 1990s, the statue was put back near 18th Street and Prairie Avenue. This was close to its first location. Later, it was removed again for care. There are talks about putting it back, but some groups are against it.

The battle is also remembered by a sculpture called Defense by Henry Hering. It is on the Michigan Avenue Bridge in Chicago. This bridge is partly over the site of Fort Dearborn. There are also memorials in Chicago for people who fought in the battle. Wells Street is named after William Wells. Heald Square is named after Nathan Heald. Ronan Park honors Ensign George Ronan, who was the first graduate of West Point to die in battle.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Fort Dearborn para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Fort Dearborn para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |