Battle of Heraklion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Heraklion |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II, Battle of Crete | |||||||

German paratroopers dropping near Heraklion; a Ju 52 is visible and the smoke (centre) marks where another has crashed after being hit by anti-aircraft fire. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

The Battle of Heraklion was a big fight during World War II on the Greek island of Crete. It happened between May 20 and 30, 1941. British, Australian, and Greek soldiers defended the city of Heraklion and its airfield. They were attacked by German paratroopers.

The German attack on Heraklion on May 20 was one of four airborne attacks on Crete that day. The Germans had problems with their planes and couldn't get enough air support. Many German paratroopers were killed as they landed or soon after. Cretan civilians also fought against the Germans. The first German attack failed, and so did the second one the next day. The fighting then became a standstill.

A German mountain division was supposed to help the paratroopers by sea, but their ships were stopped by the British navy. The main German commander, Kurt Student, decided to focus all his efforts on another battle at Maleme airfield, which the Germans won. The Allied forces on Crete were ordered to leave. The soldiers from Heraklion were picked up by warships on the night of May 28/29. On their way back, two Allied destroyers were sunk, and many soldiers were killed or captured. Because they lost so many soldiers on Crete, the Germans never tried another large airborne attack during the war.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

Greece joined World War II when Italy invaded it in October 1940. British and Commonwealth soldiers were sent to help Greece. British forces also guarded Crete, which helped the Greek army. Crete was important because it had good harbors for the British navy.

In April 1941, Germany attacked mainland Greece and quickly took control. Many Allied troops were evacuated to Crete. They often arrived without their heavy weapons. German leaders didn't really want to attack Crete at first. But Adolf Hitler was worried about attacks on oil fields from Crete. German air force leaders also wanted to capture the island. So, Hitler ordered the invasion of Crete to use it as an airbase.

Who Fought in Heraklion

Allied Forces

On April 30, 1941, Bernard Freyberg, a New Zealand general, became the commander on Crete. He noticed that the troops didn't have enough heavy weapons, equipment, or supplies. The best airfield on Crete was at Heraklion. It had a concrete runway and shelters for planes.

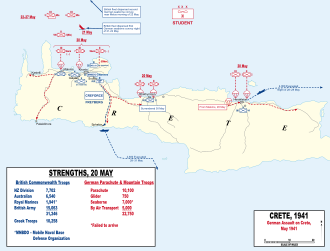

By late April, about 27,000 Allied troops arrived on Crete from Greece. Many had lost their equipment. About 18,000 of these stayed on Crete. With the soldiers already there, the Allies had about 32,000 Commonwealth troops and 10,000 Greek soldiers.

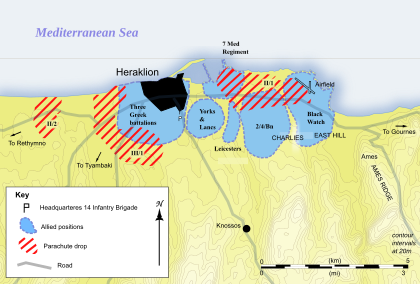

Heraklion was defended by the British 14th Infantry Brigade, led by Brian Chappel. This group included:

- The 2nd Battalion, the York and Lancaster Regiment (about 742 men).

- The 2nd Battalion, the Black Watch (about 867 men).

- The Australian 2/4th Battalion (about 550 men).

- The 2nd Battalion of the Leicester Regiment (about 637 men).

- About 450 artillerymen fighting as infantry.

- Greek 3rd and 7th Regiments (battalion-sized, but not well trained or armed).

- Other smaller units and some tanks.

In total, about 7,000 men defended Heraklion, with about 2,700 of them being Greek.

German Forces

The German attack on Crete was called "Operation Mercury." It was led by Kurt Student. Over 500 Junkers Ju 52 transport planes were gathered to carry the soldiers. Student planned four parachute attacks on Allied bases on Crete's north coast. Then, mountain troops would arrive by air and sea.

For the attack on Heraklion, the Germans sent their strongest force: the 1st Parachute Regiment and parts of other regiments. This was about 3,000 men, led by Bruno Bräuer. German intelligence thought there were only 400 Allied soldiers in Heraklion, which was a big mistake. Before the invasion, the Germans bombed Crete to gain control of the sky. The British Royal Air Force (RAF) moved its planes away after many were destroyed.

German Paratroopers

German paratroopers had special parachutes. They had to jump headfirst and couldn't carry large weapons. Rifles, machine guns, and supplies were dropped in separate containers. This meant paratroopers only had pistols or grenades until they found their weapons.

They had to jump from low heights (about 400 feet) and in light winds. This made their transport planes easy targets for ground fire. Each Ju 52 plane could carry 13 paratroopers and their weapon containers.

Battle Plans

Allied Defenses

Brigadier Chappel placed the Greek units in Heraklion town and to its west and south. The town was protected by its old walls. East of the town, Chappel placed the British and Australian battalions. The Australians were on two hills, called "the Charlies," overlooking the airfield. The Black Watch regiment was further east, near the sea, controlling the coast road and the airfield. All units were well hidden and dug in.

German Attack Plan

The German plan was to land paratroopers and gliders at Maleme airfield and near Chania in western Crete on the morning of May 20. The same planes would then drop more paratroopers at Rethymno and Heraklion in the afternoon.

Colonel Bräuer thought he would face only a small Allied force. He planned for one battalion to land near the airfield and capture it. Another battalion would land southwest of Heraklion and quickly take the town. Bräuer himself would land further east with a reserve unit. After taking the airfield and town, Bräuer planned to move his troops west.

The Battle Begins

First Attack

On the morning of May 20, the attacks on Maleme and Chania happened. The transport planes then returned to mainland Greece to pick up more paratroopers for Rethymno and Heraklion. The German airfields were dusty and chaotic, causing delays. Planes were damaged, and refueling took a long time.

The attack on Heraklion started with a strong German air raid around 4:00 PM. This was meant to stop Allied ground fire. But the Allied soldiers were ordered not to shoot back, so the Germans couldn't find their positions. The German bombers left before the paratrooper planes arrived.

Around 5:30 PM, the Ju 52 planes started dropping paratroopers. They flew straight and low, making them easy targets for Allied anti-aircraft guns and even infantry. Many paratroopers were killed in the air. One German battalion lost 400 dead or wounded in 30 minutes.

West of Heraklion, another German battalion also suffered heavy losses. Greek soldiers and armed civilians immediately fought back. The Germans tried to attack the town, but the old walls made it hard. They fought their way into the town, leading to street-by-street combat that lasted late into the night.

Another German battalion landed further west, but it was only half its normal size. The rest of its soldiers were stuck in Greece. This half-battalion blocked the coast road to Heraklion from the west.

A German reserve battalion landed successfully about 5 miles east of Heraklion around 8:00 PM. Colonel Bräuer landed with them. He couldn't contact his other battalions, but he thought the attack was going well. He then tried to attack East Hill, but the British Black Watch regiment easily stopped him. Cretan civilians also attacked the Germans, causing about 200 casualties.

Because of the chaos at the Greek airfields, German air attacks over Heraklion were not well organized. Paratroopers kept dropping for hours, giving Allied guns easy targets. A total of 15 Ju 52 planes were shot down. The German commander, Student, realized that all four paratrooper attacks had failed. He then decided to focus all efforts on capturing Maleme airfield, which was 100 miles west of Heraklion.

Sea Reinforcements

Meanwhile, German mountain troops and artillery were sailing from Greece to Crete in small Greek boats. This group was called the 2nd Motor Sailing Flotilla. They were detected by Allied intelligence. On the night of May 20, a British naval group, Force C, sailed to stop them. They didn't find the invasion force that night.

The German convoys had stayed near the island of Milos. On May 21, they headed south. Student ordered the Heraklion-bound convoy to go to Maleme instead. The boats were slow, and the Greek crews were suspected of not trying their best. The convoy was ordered back and forth several times.

Another British naval group, Force D, found a different German convoy at about 10:30 PM. The British ships attacked, sinking many small boats. About 297 German soldiers out of 2,000 were killed. The remaining German mountain troops were later flown into Crete.

Reports of these losses caused the 2nd Motor Sailing Flotilla to be called back. The British Force C re-entered the Aegean Sea. They found the main escort of the 2nd Flotilla, an Italian torpedo boat, but the German convoy managed to escape. The British warships, low on anti-aircraft ammunition, withdrew. Even though they didn't destroy the troop transports, their presence stopped the German landing by sea.

Continued Fighting

On the night of May 20/21, many isolated German paratroopers suffered from thirst. They were hunted by Allied patrols and Cretan civilians. On the morning of May 21, Bräuer attacked East Hill again, but his attacks failed with heavy losses. German air attacks continued, but the Allies used captured German signals to confuse the bombers.

West of Heraklion, the German commander Schulz tried to capture the town again. He asked for reinforcements, but only one small group arrived. After heavy bombing, the Germans attacked the town and fought their way in. The Greeks ran out of ammunition and started to surrender. But Allied reinforcements arrived, forcing the Germans to pull back. The Allies also sent captured German weapons to the Greeks.

On May 22, Greek troops and civilians cleared the areas around Heraklion. The Black Watch regiment also cleared the airfield's eastern side. German planes mistakenly dropped supplies, including motorcycles, to the Allies, who then gave the weapons to the Cretans.

On May 23, six British Hurricane fighter planes were sent to Heraklion, but they couldn't stay due to lack of fuel and ammunition. On May 24, more German paratroopers landed west of Heraklion. The town was heavily bombed. On the night of May 24/25, the Greek units were pulled back for rest. British troops, including about 340 men from the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, took over the defense of Heraklion.

The Allied plan was for one of the Heraklion battalions to move west to Rethymno. But Brigadier Chappel thought the German forces were stronger than they were, so he kept his brigade in place. By May 27, the battle for Crete was already lost. The Germans were still under attack from Cretan civilians, even though the Germans fought back fiercely.

Allied Retreat and Greek Surrender

The Germans had captured Maleme airfield and the port of Chania. On May 26, General Freyberg told Archibald Wavell, the Allied commander in the Middle East, that the Battle of Crete was lost. The next day, Wavell ordered an evacuation. The 14th Brigade was told they would be picked up by ships on the night of May 28/29.

Shortly before noon on May 28, another 2,000 German paratroopers landed east of the brigade. That afternoon, the Allies were heavily bombed for two hours. They destroyed their supplies and heavy weapons. The naval force for evacuation included three cruisers and six destroyers. One cruiser, Ajax, had to turn back due to a fire. The evacuation went smoothly, and about 4,000-4,100 soldiers were on their way by 3:00 AM. Many wounded soldiers and some guarding roadblocks were left behind. The Greeks were not told about the evacuation for security reasons, so only one Greek soldier was evacuated.

One destroyer, Imperial, broke down, and its crew and soldiers had to be rescued at sea. This delayed the squadron. At 6:00 AM, German planes spotted them. Over the next nine hours, there were 400 attacks by German dive bombers. Another destroyer, Hereward, was hit and began sinking. Italian boats rescued 165 crew and about 400 soldiers. Many others were killed. Two cruisers were also hit many times, causing heavy casualties. Allied fighter planes covered the last part of the journey, and the ships reached Alexandria by 8:00 PM.

The Germans took over Heraklion on May 30. The Greek commander signed a surrender with Bräuer, and the Greek troops laid down their weapons. They were later released over the next six months.

What Happened After

During the fighting and evacuation, the Allied troops of the 14th Brigade lost many soldiers. About 195 were killed on Crete, and 224 died during the evacuation or from wounds. An unknown number died when the Hereward sank. Many wounded were left on Crete, and 244 wounded soldiers made it to Alexandria. Many men were captured, including over 300 from the Argylls who were still trying to reach the coast. Over 200 naval personnel were killed, and 165 were captured from the Hereward. The number of Greek casualties is not known.

German losses during the battle are not exactly known. Some historians say over 1,000 were killed on May 20, and at least 1,250 by May 22. German records don't show losses at the regimental level, so it's hard to know the exact numbers. Across the whole Crete campaign, German paratrooper losses were very high, possibly over 3,000 killed and 1,500 wounded. Almost 200 Ju 52 planes were put out of action. Because of these heavy losses, Germany never tried another large airborne operation during the war.

The German occupation of Crete was harsh. Many Cretan civilians were executed. Bräuer was the German commander on Crete for a while. After the war, he was charged with war crimes by a Greek court. He was found guilty and executed on May 20, 1947, exactly six years after the invasion.

After the Germans captured it, Heraklion airfield was used to send supplies and soldiers to German forces in North Africa. Allied special forces successfully raided it in June 1942. Today, it is a busy international airport, the second busiest in Greece.

Images for kids