Battle of Krasnoi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Krasnoi |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French invasion of Russia | |||||||

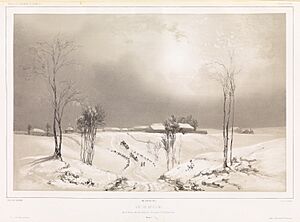

Battle of Krasnoi on 17 November 1812, by Peter von Hess |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 41,500 combatants 35,000 stragglers |

50,000 to 60,000 regular troops 20,000 Cossack cavalry 500 cannon |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5 to 13,000 killed, wounded or drowned soldiers and stragglers 26,500 prisoners (almost all stragglers) and 228 cannon. |

2,000 to 5,000 killed and wounded | ||||||

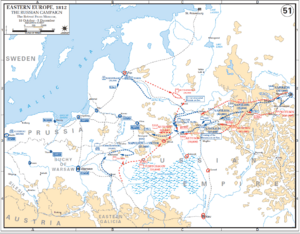

The Battle of Krasnoi happened near Krasny in Russia. It took place from November 15 to 18, 1812. This battle was a very important part of Napoleon's difficult retreat from Moscow. Over four days, Russian forces led by General Kutuzov attacked the remaining parts of Napoleon's army, called the Grande Armée.

Napoleon's army was already very weak from fighting and the harsh weather. Even though these were not huge, full-scale battles, the French lost many soldiers. They also lost a lot of their weapons and horses.

Napoleon tried to quickly move his troops, who were spread out over 30 miles, past the Russian army. The Russians were waiting along the main road. General Kutuzov had more soldiers, but he didn't launch a full attack. He thought that hunger, cold, and a lack of discipline would weaken the French army enough.

On November 17, the French Imperial Guard made a brave move to trick the Russians. This made Kutuzov pause his attack. This delay allowed Napoleon to save some of his troops. However, Napoleon had to retreat quickly before the Russians could capture Krasny. Kutuzov chose to chase the French army constantly, using smaller groups to wear them down.

The French army had split into different groups, which caused big problems. Many soldiers from the groups of Eugene, Davout, and Ney were defeated. The Russians captured many prisoners, including generals and officers. The Grande Armée also had to leave behind most of its cannons and supplies.

Overall, the Battle of Krasnoi caused huge losses for the French army. It made their already terrible retreat even worse. Even with the brave efforts of the Imperial Guard, the French army was in a very bad situation. They had no supplies and were very weak.

Contents

Armies Meet at Krasny

Napoleon Leaves Smolensk

Napoleon's Grande Armée left Moscow on October 18. They had 100,000 soldiers ready to fight, but not enough supplies. They wanted to find winter homes by taking a different route to Kaluga. But after losing the Battle of Maloyaroslavets, Kutuzov forced Napoleon to go back the same way they came. This path was already destroyed.

Smolensk, about 360 km (224 miles) west, was the closest French supply base. The three-week march to Smolensk was a disaster, even with good weather. The Grande Armée faced many problems. They marched through empty forests and abandoned villages. Soldiers lost hope, discipline broke down, and they were hungry. They lost many horses and important supplies. Cossack soldiers and partisans constantly attacked them, making it impossible to find food.

When they reached Smolensk around November 8-9, only about 37,000 soldiers were still able to fight. The situation got even worse when a very cold "Russian Winter" started around November 5-7. Many men and horses froze to death. Napoleon realized he couldn't stay in Smolensk because Russian armies were closing in. His new goal was to lead his army west to Minsk, where there was a large French supply depot.

Napoleon thought the Russian army was also suffering a lot. He decided to continue his retreat, sending his army's different groups from Smolensk on separate days. This created a long, spread-out line of soldiers, about 50 km (31 miles) long. They were not ready for a big battle.

On November 14, a huge blizzard hit. About 1.5 meters (5 feet) of snow fell, and the temperature dropped to -25°C (-14°F). This caused more soldiers and horses to die, and more cannons were left behind.

By the afternoon of November 15, Napoleon arrived at Krasny with his 14,000-strong Imperial Guard. He planned to wait for the other groups of soldiers to arrive. But between these French groups, there were almost 40,000 unarmed, disorganized soldiers who had given up.

Kutuzov's March South

At the same time, the main Russian army, led by Kutuzov, followed the French on a parallel road to the south. This route went through Medyn and Yelnya, which was a center for partisan fighters. The Russian army was in much better shape than the French, but they also faced the extreme cold. Kutuzov wanted the French army to retreat easily and at first told his generals not to cut off their escape.

Kutuzov thought that only a small part of the French army had passed through Smolensk. He believed the rest were still far north or in Smolensk. So, he agreed to a plan to march on Krasny to destroy what he thought was a small, isolated French group.

The Russian army started to gather at Krasny on November 15. A group of 3,500 Russian soldiers, led by Adam Ozharovsky, took over the town. On the same day, 18,000 Russian soldiers under Miloradovich took a strong position on the main road, about 4 km (2.5 miles) before Krasny. This move cut off the French groups of Eugene, Davout, and Ney from Napoleon.

On November 16, Kutuzov's main force of 35,000 soldiers slowly came closer. Another 20,000 Cossack soldiers attacked the French along the long road to Krasny.

In total, Kutuzov had 50,000 to 60,000 regular soldiers, including many cavalry and about 50 to 200 cannons. His army was split into two groups. The larger group, led by General Alexander Tormasov, moved around Krasny to stop Napoleon from escaping. The second group, led by Prince Dmitry Golitsyn and Pavel Alexandrovich Stroganov, attacked Krasny itself. Miloradovich's soldiers held a key position on a road to Krasny. This road made the French cross a stream in a deep valley.

November 15: Ozharovsky's Defeat

Near Smolensk, the road goes down into a long, gentle slope towards Krasny. Around noon, Napoleon and his Imperial Guard marched past Miloradovich's troops. Miloradovich had orders not to attack the Guard. He only fired cannons from far away, which did little damage.

As Napoleon and the Imperial Old Guard got closer to Krasny, Ozharovsky's Russian infantry and artillery fired at them. The French army was surprised because they didn't expect attacks from the front. Soon after, Vasily Orlov-Denisov's Cossacks attacked the Imperial Guard. They captured 1,300 soldiers, 400 carts, and 1,000 horses.

Before it got dark, Napoleon and his Guard entered Krasny. He planned to stay for at least a day for Eugene and Davout to catch up. But parts of the town caught fire. Napoleon decided to force Ozharovsky's 3,500 Cossacks to leave the Losvinka area.

After midnight, Napoleon sent the Young Guard, led by General Michel Claparede, to surprise Ozharovsky's camp. The Russians were sleeping and had no guards. General François Roguet led the attack. The Young Guard moved quietly through knee-deep snow. They attacked Ozharovsky's camp and drove his soldiers away. The Russians were surprised and, despite fighting hard, were defeated. About half of Ozharovsky's soldiers were killed or captured. The rest threw their weapons into a pond and ran away. Roguet couldn't chase them because he had no cavalry.

November 16: Eugene's Defeat

Miloradovich Attacks

On November 16, things got worse for the French. Kutuzov's forces got closer to the main road but didn't attack. However, Miloradovich's troops heavily defeated Prince Eugène de Beauharnais. Eugene refused to surrender. In this fight, his Italian Corps lost a third of its soldiers, all its supplies, and cannons at the Losvinka.

With only 3,500 soldiers left, and no cannons or supplies, Eugene had to wait until night. Then he found another way around the Russian forces. He tricked the Russian general by attacking his army on the left side, but then escaped with some soldiers to the right. This escape happened partly because Kutuzov held back Miloradovich. Kutuzov didn't want the fight to become a full battle.

Kutuzov at Zhuli

Earlier that day, Kutuzov's main army finally arrived near Krasny. They took positions around the villages of Novoselye and Zhuli. Even though they were in a good spot to attack the French, Kutuzov waited. He decided his troops needed a day of rest.

In the evening, some younger generals, like Wilson, pushed Kutuzov to attack Napoleon. But Kutuzov remained careful. He only planned an attack and told his commanders not to start until daylight. The Russian plan was to attack Krasny from three sides. Miloradovich would stay on the hill to block Davout and Ney. The main army would split: Golitsyn would lead 15,000 soldiers to the Losvinka, and Tormasov would lead 20,000 soldiers to surround Krasny. This would cut off the French escape route to Orsha.

However, Kutuzov learned that Napoleon planned to stay in Krasny and wait for Ney. This changed Kutuzov's mind about the planned attack.

November 17: Napoleon's Bold Move

Danger for Davout

At 3:00 a.m., Davout's I Corps started marching towards Krasny. They had heard bad news about Eugene's defeat. Davout had planned to wait for Ney's III Corps, which was still in Smolensk. But he saw a clear path and reached the Losvinka around 9:00 a.m.

Then, Miloradovich, with Kutuzov's permission, started a huge cannon attack on Davout's soldiers. This surprise attack caused panic. The French troops quickly retreated from the road. Davout's group suffered many losses, with only 4,000 men left.

During this time, some of Davout's supplies, including his war chest and important maps, were captured by Cossacks near the Losvinka. His Marshal's baton was also taken.

Napoleon Orders the Guard's Advance

Napoleon realized his army was in great danger. Waiting for Ney in Krasny was no longer an option. A strong attack by Kutuzov could destroy his entire army. Also, his starving troops needed to reach their closest supply source, Orsha, about 40 km (25 miles) west.

In this critical moment, Napoleon became very determined. He prepared his Imperial Guard for a bold move against Golitsyn. He hoped this surprise would stop the Russians from attacking Davout. The Guardsmen formed attack lines, and the remaining French cannons were ready. Napoleon's plan was to hold off the Russians long enough to gather Davout's and Ney's troops. Then, they would continue retreating before Kutuzov could attack them.

The Imperial Guard Shows its Strength

At 2:00 a.m., 11,000 Imperial Guards (4 regiments) marched out of Krasny. They went to secure the area east and southeast of the town. For the first time, Napoleon used his Old Guard, which were 6,000 tall, experienced soldiers. They faced Cossacks blocking the road. Napoleon said, "I have played the Emperor long enough! It is time to play general!"

The Guardsmen faced Russian soldiers and powerful cannons to the south and east. But the Young Guards didn't have enough cannons. A French officer described it: "Russian battalions and batteries blocked the view on all three sides."

Kutuzov's reaction to the Imperial Guard's bold move was to cancel his planned attack. This was surprising because the Russians had many more soldiers.

In the morning, Miloradovich moved south to help Golitsyn against the Young Guards. When Miloradovich left his position, he left only a small group of Cossacks. This allowed Davout to fight his way through and enter Krasny. The Guard's brave move helped Napoleon save Davout's group from being destroyed.

Fighting at the Losvinka Brook

On this day, there was limited close fighting around Uvarovo in the center. The Young Guard attacked to help Davout cross the Losvinka further north.

Uvarovo was held by two groups of Golitsyn's soldiers. The Russians were eventually forced out of Uvarovo. In response, Golitsyn fired many cannons, causing heavy losses for the Young Guardsmen.

Kutuzov ordered Miloradovich to move and join Golitsyn's lines. This move, however, stopped Miloradovich from completely destroying Davout's troops.

Meanwhile, Davout's troops kept moving west, constantly attacked by Cossacks. Russian cannons fired grapeshot at Davout's group, causing terrible losses. Many of Davout's soldiers were saved and gathered in Krasny. As soon as Davout and Mortier connected, Napoleon began his retreat towards Lyady with the Old Guard and cavalry.

Davout's rear guard faced attacks from Cossacks, cavalry, and infantry. They were surrounded and ran out of ammunition. They formed defensive squares and fought off the attacks. But during the third Russian attack, they were trapped. Most of the regiment was killed or captured, with only 75 men surviving.

Around 11:00 a.m., Napoleon received news that Tormasov's troops were moving west of Krasny. This forced Napoleon to change his plan. He couldn't wait for Ney's III Corps anymore. The risk of being surrounded by Kutuzov's forces was too great. Napoleon decided to order the Old Guard to fall back to Krasny and follow him west towards Lyady. The exhausted Young Guard would stay and hold their ground at the Losvinka.

The Young Guard was quickly losing its ability to fight. Mortier wisely ordered a retreat before the remaining troops were surrounded. The Guardsmen turned around and marched back to Krasny. They faced a final heavy cannon attack from the Russians as they retreated at 2:00 p.m. Only 3,000 soldiers survived from the Young Guard's original 6,000. Many wounded soldiers were left behind and died in the snow.

The Young Guard's retreat didn't stop at Krasny. Mortier and Davout, worried about a Russian attack, joined the hurried movement of troops and wagons towards Lyady. Only a small group of soldiers, led by General Friederichs, stayed behind to hold Krasny.

Napoleon's Retreat

Before noon, Napoleon and the Old Guard, followed by the remaining I Corps, started their westward journey from Krasny. The road to Lyady quickly became crowded with soldiers and their heavy wagons. Many civilians and people who had given up also moved ahead of the French troops.

Just outside Krasny, Davout's forces fell into an ambush by small groups of Ozharovsky and Rosen's soldiers. This caused heavy damage to his rear guard. Chaos followed, with exploding cannon fire, overturned wagons, and panicked crowds. But the Red Lancers and other cavalry managed to push the Russians aside. Napoleon himself was present, and he even burned his important papers and records.

After marching for about an hour, Napoleon gathered the Old Guard and formed them into a square. He got off his horse because the road was too slippery. Napoleon told them, "Grenadiers of my Guard, you see how disorganized my army is." He then walked at the front of his Old Guard with his walking stick. It kept snowing, even though the temperature rose.

Kutuzov Delays the Chase

Even though the Russians wanted to chase the French and attack Krasny, Kutuzov held them back. This caused several hours of delay. Tormasov had set up his troops across a wide valley and blocked a bridge.

At 2:00 p.m., Kutuzov finally allowed Tormasov to move west. But by the time Tormasov reached his goal, it was too late to surround Davout's group. Some French soldiers were even given free passage to Orsha, where they stayed for 24 hours. The whole French army was surprised by how calm the Russians were.

Around 3:00 p.m., Golitsyn's troops stormed into Krasny with great force. Friederichs' rear guard quickly gave in and left Krasny. By nightfall, Golitsyn's troops controlled Krasny. The enemy strengthened their position and waited for Ney, whom Napoleon was forced to leave behind.

November 18: Ney's III Corps is Destroyed

Ney's III Corps was the last group to leave Smolensk. Ney tried to destroy the city walls and many supply wagons, but it didn't work well because of the rainy weather. He left Smolensk with about 6 cannons, 6,000 soldiers, and 300 horses.

Around 3:00 p.m. on November 18, Ney's Corps set out for Krasny. Miloradovich had placed his troops on a hill overlooking a valley with the Losvinka stream. On this day, the weather was thawing, with thick fog and light rain. This created very slippery, icy surfaces as evening came. Ney didn't know that the main French army had already left Krasny. He didn't realize the danger near the valley.

Around 3:00 p.m., Ney's advance group reached the Losvinka. They briefly got to the top of the hill but were pushed back. Ney thought Davout was still behind Miloradovich's soldiers in Krasny. Ney bravely decided to fight his way through the enemy forces, even though the Russians offered him a chance to surrender. His determined soldiers broke through the first Russian lines, but the third line was too strong. Nikolay Raevsky launched a fierce counterattack. Ney's troops were surrounded on the hill, causing great confusion, and many surrendered.

Ney lost more than half of his soldiers. Almost all his cavalry and all but two cannons were gone. Miloradovich offered Ney another chance to surrender. In the early evening, Ney chose to retreat with his remaining 3,000 soldiers. He followed advice to go around the Russian forces. They walked for hours along the Losvinka's path. By 9 p.m., they reached a deserted place about 13 km (8 miles) north. There, they found some food.

During the night, Ney learned of the danger. He decided to bravely cross the Dnieper River. They found shallow spots in the river, but the banks were very steep. Engineers used logs and planks to make makeshift crossings over the ice. Many soldiers were lost, but they managed to cross, leaving behind two cannons, some soldiers, and the wounded. Ney's men crawled on their hands and knees. The weather and the Cossacks reduced their numbers to only 800 or 900 determined soldiers.

For the next two days, Ney's brave group fought off Cossack attacks. They traveled 90 km (56 miles) west along the river, going through swamps and forests to find the French army. Ney refused to surrender, even as Platov's thousands of Cossacks chased them. The French soldiers' spirits were broken, and some thought about surrendering.

On November 20, at 3:00 a.m., Ney and Beauharnais met near Orsha. This reunion brought hope to the French troops. Ney's courage earned him the nickname "Bravest of the Brave" from Napoleon.

Battle Results

Historians have different ideas about the Battle of Krasnoi. Older books sometimes say it was a French victory, focusing only on the Imperial Guard's actions. But newer accounts see it as a Russian win, even if it wasn't a complete destruction of Napoleon's army. Napoleon made a big mistake because the enemy wasn't just behind him, but also moving on a side road. Kutuzov had cut off Napoleon and defeated Davout's group.

The French losses at Krasny are estimated to be between 6,000 and 15,000 killed. About 1,200 wounded soldiers were treated. An additional 26,000 French soldiers were captured by the Russians, most of whom were stragglers. The French also lost about 230 cannons and many supplies and cavalry. Russian losses were much smaller, estimated at no more than 5,000 killed and wounded.

For several days, French soldiers had very little food. Temperatures were extremely cold, from -12 to -25°C (-13°F), with strong winds and snow. Their feet were often wet from the thawing snow. Orders were often delayed or didn't reach the soldiers at all.

According to Minard's map, about 24,000 men reached Orsha. Napoleon entered Orsha with 6,000 guards (from an original 35,000). Eugene had 1,800 troops (from 42,000), and Davout had 4,000 (from 70,000). When Napoleon reunited with Ney, it gave the French troops hope. This helped them prepare for the upcoming Battle of Berezina.

Krasny was definitely a Russian victory, but it wasn't as complete as some hoped. Tsar Alexander I was disappointed that Kutuzov didn't completely destroy the remaining French forces. However, because Kutuzov was very popular, Alexander gave him the special title of Prince of Smolensk for his success in this battle.

It's not clear why Kutuzov didn't completely wipe out the French army. Some historians suggest he didn't want to risk the lives of his own tired and cold soldiers. Kutuzov himself said, "All that [the French army] will collapse without me."

See also

- First Battle of Krasnoi

- Moscow 1812: Napoleon's Fatal March

Sources

- Napoleon's Russian Campaign of 1812, Edward Foord, Boston, Little Brown and Company, ISBN: 9781297620355

- Russia Against Napoleon, Dominic Lieven, Penguin Books, ISBN: 978-0-14-311886-2

- With Napoleon in Russia, Caulaincourt, William Morrow and Company, New York, ISBN: 0-486-44013-3

- Napoleon in Russia: A Concise History of 1812, Digby Smith, Pen & Sword Military, ISBN: 1-84415-089-5

- The War of the Two Emperors, Curtis Cate, Random House, New York, ISBN: 0-394-53670-3

- Narrative of Events during the Invasion of Russia by Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Retreat of the French Army, 1812, Sir Robert Wilson, Elibron Classics, ISBN: 978-1-4021-9825-0

- Moscow 1812: Napoleon's Fatal March, Adam Zamoyski, HarperCollins, ISBN: 0-06-107558-2

- The Fox of the North: The Life of Kutusov, General of War and Peace, Roger Parkinson, David McKay Company, ISBN: 0-67950-704-3

- Napoleon 1812, Nigel Nicolson, Harper & Row, ISBN: 0-06-039043-3

- The Napoleonic Wars, The Rise and Fall of an Empire, Gregory Fremont-Barnes & Todd Fisher, Osprey Publishing, ISBN: 1-84176-831-6

- The Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Data Source, Digby Smith, Greenhill Books, ISBN: 1-85367-276-9

- The Campaigns of Napoleon, David Chandler, The MacMillan Company, ISBN: 0-02-523660-1

- Napoleon's Invasion of Russia 1812, Eugene Tarle, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 0-374-97758-5

- Napoleon's Russian Campaign, Philippe-Paul de Segur, Time-Life Books, ISBN: 0-8371-8443-6

- 1812 Napoleon's Russian Campaign, Richard K. Riehn, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., ISBN: 0-471-54302-0

- Napoleon in Russia, Alan Palmer, Carrol & Graf Publishers, ISBN: 0-7867-1263-5

- In the Service of the Tsar Against Napoleon, by Denis Davydov, Greenhill Books, ISBN: 1-85367-373-0

- Atlas of World Military History, Brooks, Richard (editor). London: HarperCollins, 2000. ISBN: 0-7607-2025-8

- Beyond Smolensk by Peter Hicks

- Mémoires militaires et historiques pour servir à l'histoire de la guerre depuis 1792 jusqu'en 1815 inclusivement, Band 5, Chapter XLVIII, p. 86-105 by Jean Baptiste Louis baron de Crossard (1829)

- Histoire de la campagne de Russie en 1812 par Alexandre Furcy Guesdon (1829)

- Relation circonstanciée de la campagne de Russie... par Eugène Labaume (1814)

- La Grande Armée de 1812, organisation à l'entrée en campagne par François Houdecek

- "Campagne et captivité en Russie, extraits des mémoires inédits du géneral-major H.P. Everts, traduits par M.E. Jordens" Carnet de la Sabretache, 1901, p. 698

- Memoirs of sergeant Bourgogne (1853), p. 110-115

- D. Buturlin (1824) Histoire militaire de la campagne de Russie en 1812, p. 217

- Mémoires du général Rapp (1823)

- Manuscript of 1812 by Baron Fain (1827)