Battle of Mohrungen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Mohrungen |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Fourth Coalition | |||||||

Dohna Palace in Morąg (Mohrungen) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 12,000 36 guns |

9,000 to 16,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,096 to 2,000 | 1,400 to 2,000 | ||||||

The Battle of Mohrungen happened on January 25, 1807. It was a fight between a large part of the French army, led by Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, and a strong group of Russian soldiers, led by Major General Yevgeni Ivanovich Markov. The French managed to push back the main Russian force.

However, a surprise attack by Russian cavalry on the French supplies made Bernadotte stop his attacks. After dealing with the cavalry, Bernadotte pulled his troops back. The town of Mohrungen was then taken over by the army of General Levin August, Count von Bennigsen. This battle took place in and around Morąg in northern Poland. Back in 1807, this area was known as East Prussia. This battle was part of the War of the Fourth Coalition during the Napoleonic Wars.

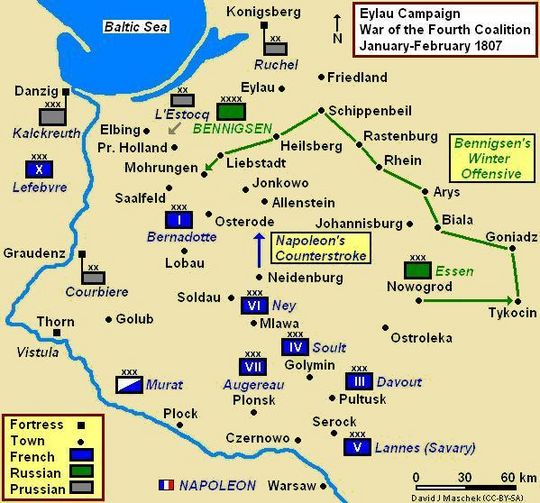

After quickly defeating the army of the Kingdom of Prussia in late 1806, Napoleon's main army, called the Grande Armée, took control of Warsaw. After two tough battles against the Russian army, Napoleon decided his soldiers needed a break for winter. But the Russian commander, General Bennigsen, moved his army north into East Prussia. He then attacked Napoleon's left side. As one of Bennigsen's groups moved west, they met Bernadotte's forces. The Russian attack was almost over as Napoleon prepared a strong counter-attack.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

After battles in December 1806, like Czarnowo, Pułtusk, and Gołymin, both the Russian and French armies settled down for winter. Emperor Napoleon wanted time to get his army's supplies in order. His experienced French soldiers were also tired of fighting in Poland during the cold winter.

In late 1806, the Russian army in Poland was split into two main groups. One was led by General Bennigsen, and the other by General Friedrich Wilhelm von Buxhoeveden. Bennigsen's group had about 49,000 foot soldiers and 11,000 cavalry, plus artillery. Buxhöwden's group was smaller, with about 29,000 foot soldiers and 7,000 cavalry. The Prussian army at this time had only about 6,000 soldiers ready to fight.

The Russian army had 18 divisions. Each division was very strong, with many infantry regiments, cavalry squadrons, and lots of cannons. A typical Russian division could have up to 82 cannons.

The overall Russian commander, Marshal Mikhail Kamensky, was 75 years old and not well. He left the front, and his two main generals, Bennigsen and Buxhöwden, started competing for command. Eventually, Czar Alexander appointed Bennigsen as the new army commander.

Napoleon had spread his army out in a wide arc east of the Vistula River, protecting Warsaw. Marshal Bernadotte's I Corps was on the far left side. Other marshals like Michel Ney, Nicolas Soult, Louis-Nicolas Davout, and Jean Lannes were positioned across the front. Marshal Pierre Augereau's VII Corps was held in reserve.

The Russian Attack Begins

On January 2, 1807, the Russian generals decided to attack the French. Their plan was to move north into East Prussia with most of their army. Then, they would turn west to attack Napoleon's left side. They hoped to force the French army to retreat back across the Vistula River. This would give them a good position for a spring campaign.

General Bennigsen moved his six divisions east and then north. He was happy to learn that the Czar had made him the main army commander. He arrived in Biala Piska on January 14. Bennigsen's movements were hidden from the French by a large forest. The Prussian forces, led by General-Leutnant Anton Wilhelm von L'Estocq, pulled back north.

Meanwhile, Marshal Ney, whose soldiers were running out of food, ignored Napoleon's orders and moved far north. On January 11, his advance group pushed back a Prussian attack. Napoleon was very angry with Ney for not following orders. But he started to prepare his army in case the Russians reacted to Ney's move.

On January 19, the Russians finally appeared from the forests. They pushed Ney's troops back. Bennigsen now had about 63,000 soldiers, and L'Estocq had 13,000. On January 21, the first Russian groups were in Heilsberg. Ney managed to escape south.

After dealing with Ney, the Russians moved towards Bernadotte's army. On January 24, General Markov's Russian troops attacked a French unit near Liebstadt, capturing 300 French soldiers. Bernadotte quickly gathered his forces. He ordered General Pierre Dupont to march to attack the Russian left side. Bernadotte's chief of staff also alerted other French divisions to get ready.

The Battle of Mohrungen

At noon on January 25, General Markov's Russian advance guard reached Mohrungen. Markov knew that Bernadotte was gathering his troops there. Bernadotte had about 9,000 soldiers, including infantry and cavalry. When Markov appeared, Bernadotte immediately moved forward to fight. He told Dupont to march from Preussisch Holland to attack the Russian right side.

Markov's advance guard included several infantry and cavalry regiments, with many cannons. The Russian forces in total were between 9,000 and 16,000 men. Bernadotte had about 9,000 soldiers ready to fight until Dupont arrived.

Bernadotte used Dupont's division, which had seven battalions. He also had the 8th Light Infantry Regiment and Drouet's division. The French had 36 cannons. Their cavalry included hussars and chasseurs.

Markov sent one infantry regiment forward, with his hussars in front. His main line was on high ground. Three battalions of Russian light infantry held a village called Georgenthal.

Around 1:00 PM, Bernadotte's cavalry attacked the Russian hussars. The Russian hussars pushed them back but then faced French cannons. The French cavalry chased the Russians, but they too were stopped by enemy cannons. Bernadotte then sent his infantry to attack the Russian positions. The fighting was tough, but the French managed to clear out the Russian regiment.

Markov had to send six battalions to protect his right side from Dupont's attack. As it got dark, Bernadotte attacked from the front. Dupont's attack on the Russian side started to succeed, and Markov ordered his troops to pull back. A Russian general named Anrep arrived with news of cavalry reinforcements, but he was soon wounded and later died. The Russians fought hard as they retreated. Dupont pushed back two regiments and moved closer to Georgenthal.

Suddenly, Bernadotte heard gunfire behind him in Mohrungen. He immediately stopped the battle and rushed back to the town. What had happened was that Russian cavalry had reached the town from the east. General Golitsyn, leading the Russian cavalry, had sent some squadrons to scout the area. These Russian horsemen entered Mohrungen as night fell. They captured the few defenders and took supplies from the baggage trains in the town.

Trying to make the most of their success, the Russian raiders moved north. But they ran into Bernadotte's returning troops and quickly retreated. Most of the Russian raiders escaped. They took about 360 French prisoners, freed 200 Russian and Prussian prisoners, and carried off some of the supplies they had taken.

Aftermath of the Battle

Historians say the French lost about 696 soldiers killed or wounded, and 400 were captured. The Russians had about 1,100 killed or wounded, and 300 were captured. Russian General Anrep was killed in the battle. Bernadotte reported that his army lost 700 or 800 soldiers, while the Russians lost about 1,600.

The next day, Bernadotte retreated south to Liebemühl. Bennigsen's Russian troops then occupied Mohrungen. Markov followed the French towards Liebemühl. Another Russian group took control of Allenstein. On January 28, Bennigsen decided to stop operations at Mohrungen so his tired soldiers could rest. Bernadotte continued to retreat south until he reached Löbau. There, he joined another French cavalry division, giving him about 17,000 infantry and over 5,000 cavalry.

Meanwhile, a Prussian army group under General L'Estocq was approaching the town of Graudenz. This town had been under siege by French-allied forces. When L'Estocq arrived, the French-allied forces lifted the siege. This allowed the Prussians to resupply the town, which helped them resist the siege until the end of the war. A Russian advance group, led by General Pyotr Bagration, connected L'Estocq's forces with Bennigsen's main army.

Bennigsen was happy with his success and expected Napoleon to retreat. But Napoleon had a surprise in store. Instead of retreating, the French emperor launched a dangerous counterattack on February 1. Napoleon saw a chance to attack the Russian army's left side and rear. He ordered Bernadotte to keep retreating to draw Bennigsen further into the trap.

On February 1, the Russian commander had a stroke of good luck. The orders for Bernadotte were given to a new officer. This officer rode straight into a group of Russian Cossacks and couldn't destroy his message. Soon, General Bagration had the important document, which he sent to his commander, Bennigsen. As soon as Bennigsen got the news, he ordered his army to retreat quickly. Because of this, Bernadotte didn't know about Napoleon's plan until February 3 and missed the major Battle of Eylau on February 7 and 8. In the meantime, the French and the retreating Prussians and Russians fought several smaller battles.

Images for kids

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |