Battle on Snowshoes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1758 Battle on Snowshoes |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French and Indian War | |||||||

A 1776 artist's rendition of Robert Rogers, whose likeness was never made from life |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Ensign Joseph de la Durantaye Ensign Jean-Baptiste de Langy |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| about 300 | 181 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 6 killed, 24 wounded (many of whom died of their wounds) | 144 killed 7 captured |

||||||

The 1758 Battle on Snowshoes was a fight during the French and Indian War. It happened on March 13, 1758. British soldiers called Rangers, led by Robert Rogers, fought against French troops and their Indian allies. The battle took place near Lake George in what is now northern New York. Back then, this area was a frontier between British and French lands. The battle got its name because the British soldiers were wearing snowshoes in the deep snow.

Rogers led about 180 rangers and regular soldiers. Their job was to scout out French positions. However, the French commander at Fort Carillon already knew they were coming. He sent a group, mostly made up of Indians, to meet them. In a tough fight, the British group was almost completely wiped out. More than 120 soldiers were killed or hurt. The French thought Rogers had died because he left his jacket, which had his important papers, when he escaped.

This battle is also famous for a story about Rogers. People say he escaped by sliding 400 feet (120 meters) down a rock face. He supposedly landed on the frozen Lake George. That rock is now called Rogers Rock or Rogers Slide.

What Led to the Battle?

The French and Indian War started in 1754. It was a fight between British and French colonists. They argued over land along their borders. By 1756, the French were winning most of their battles. Their only big loss was in 1755 at the Battle of Lake George. Here, the British stopped them from moving south.

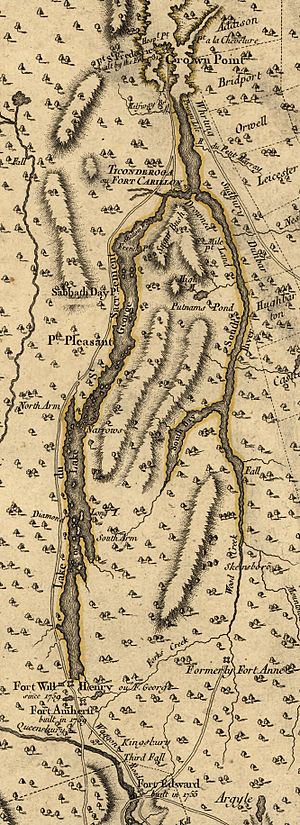

The French had forts at Fort St. Frédéric (now Crown Point, New York) and Fort Carillon (also known as Fort Ticonderoga). From these forts, the French and their Indian allies often scouted British defenses. These defenses were around Lake George and the Hudson River. The British had fewer Indian allies. So, they used special groups of colonial rangers for scouting. These ranger groups were led by Robert Rogers. They became very well known as Rogers' Rangers.

Getting Ready for the Fight

Captain Rogers was sent on a scouting trip. He left Fort Edward and headed north towards Fort Carillon on March 10, 1758. Lieutenant Colonel William Haviland was the fort's commander. He first planned for 400 men to go. But he cut the number down to 180. He did this even though he thought the French knew about the mission. The French had captured a man from an earlier British trip. They suspected he had told the French about the British plans.

Rogers' group was mostly made up of his rangers. But it also included some volunteer soldiers from the 27th Regiment. On March 13, they marched through snow that was four feet deep. They wore snowshoes to help them move. They had a small stream on their left and a steep mountain on their right. This mountain separated them from Lake George. They stopped for a three-hour break. Then, their lead scouts saw about "ninety-six, chiefly Indians."

Meanwhile, at Fort Carillon, the French commander, Captain Louis-Philippe Le Dossu d'Hébécourt, heard rumors. Indian allies told him the British were getting close. He sent Ensign Durantaye with 200 Nipissing Indians and about 20 Canadians. But they didn't find anything. The next day, two Indian scouts reported finding enemy tracks. Around noon on March 13, Durantaye led 100 men out of the fort. These were a mix of Indians and Canadians. Soon after, 200 more Indians followed under Ensign de Langy.

The two French groups joined up. But Durantaye's group was about 100 yards (91 meters) ahead of Langy's. This is when Rogers' men spotted them.

The Battle Begins

Rogers' men quickly set up a surprise attack. When Durantaye's men came close enough at 2:00 PM, the British opened fire. Rogers reported that they killed "above forty Indians." Durantaye's group broke apart and ran away in confusion. Rogers and about half his men chased after them. But they made a critical mistake: they forgot to reload their muskets.

Langy's men, who heard the gunfire, quickly set up their own ambush. When Rogers' men arrived, Langy's attack killed or wounded about 50 British soldiers. The Rangers fought bravely, even though they were outnumbered. Their numbers were quickly dropping. They tried several times to stop the French from surrounding them. But after an hour and a half of heavy fighting, their group was much smaller. The remaining British soldiers tried to escape. Rogers and some of his men got away. However, one group of British soldiers surrendered, but they were then killed.

What Happened After

Rogers and his much smaller group returned to Fort Edward on March 15. The French first thought Rogers had been killed. But he had actually survived. This idea came from how Rogers escaped. He left some of his things behind, including his military coat. This coat had his important army papers inside.

This event also started a local legend. People say Rogers escaped the battle by sliding 400 feet (120 meters) down the side of a hill. He supposedly landed on the frozen Lake George. There is no proof this happened. But the rock face he supposedly slid down quickly became known as Rogers' Slide.

The reports about how many people were hurt, and how many soldiers fought, were very different. Rogers said the French-Indian force had 700 men. He claimed they had 100 to 200 casualties. But other people doubted his reports. They didn't match other accounts. A letter from Henry Pringle, who was held captive by the French, helped clear Rogers' name. It explained how the French had a big advantage after their second ambush. Rogers went on to rebuild his groups. He also fought in the Battle of Carillon in July 1758.