Belmont (Chevy Chase, Maryland Subdivision) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Belmont

|

|

|---|---|

|

Undeveloped subdivision

|

|

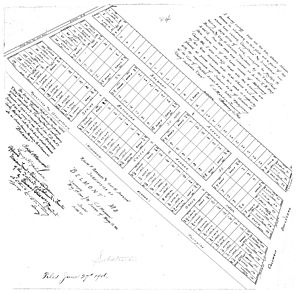

Recorded plat of Belmont.

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | |

| County | Montgomery |

| Subdivision | 1906 |

| Extinguished | 1926 |

Belmont was a piece of land in Chevy Chase, Maryland. It was located along Wisconsin Avenue. In 1906, a group of African American investors bought this land. They planned to sell smaller pieces, called lots, to other African Americans. Their goal was to create a fancy new neighborhood. This neighborhood would be for the many Black middle-class families in Washington, D.C. If it had worked, Belmont would have been one of the first modern suburbs built for African Americans.

However, white people living nearby did not like this plan. Residents from Friendship Heights, Somerset, and Drummond were against it. The company that originally owned the land, the Chevy Chase Land Company, stopped the African American group from selling the lots. This caused the investors to lose their money. Their project failed in 1909.

In 1926, the Chevy Chase Land Company officially removed Belmont from the county's property records. They added some of the land to Chevy Chase Section 1A. The rest of the land, right next to Wisconsin Avenue, was developed much later. Today, you can find a Saks Fifth Avenue store and a shopping center there.

Contents

The Story of Belmont

How the Land Was Acquired

Before 1906, the Belmont land belonged to Ralph P. Barnard and Guy H. Johnson. They were lawyers from Washington. In 1903, they bought the land for themselves and two bankers. These bankers were R. Golden Donaldson and Frank P. Reeside. They borrowed money from the Chevy Chase Land Company. They used a "deed of trust" to secure this loan. This is a legal paper that gives a lender rights to a property if a loan isn't paid.

By November 1904, they paid off their debt. The Union Trust Bank then released 20 Belmont lots to Reeside. These lots were held for Barnard, Johnson, and Donaldson. In 1906, Barnard and Johnson planned to sell the lots with Harry M. Martin.

A Dream for a New Community

Instead, on June 23, 1906, they sold the whole property. The buyer was William J. Sheetz, a white engineer. But Sheetz was a "straw buyer." This means he bought the land for someone else. He was secretly working for four Black investors. These investors were Alexander L. Satterwhite, James L. Neill, Michel O. Dumas, and Charles S. Cuney.

Sheetz quickly sold Belmont to Satterwhite and Dumas. They were part of the "Belmont Syndicate." This was a group formed by the four investors. They worked together to buy the land and share any profits.

On July 1, 1906, an advertisement appeared in The Washington Post. It said, "Colored People Attention." The ad invited African Americans to buy "an ideal suburban lot." It called Belmont "the only good subdivision in Washington where colored people are welcomed to buy."

Facing Opposition

Within days, white neighbors in the area reacted strongly. On July 5, The Washington Times reported their opposition. Residents of Friendship Heights, Drummond, Somerset, and Bethesda wanted to stop the sales. Richard M. Ough, a builder, stated that "no negro shall ever build a house in Belmont." He said white people would not accept it. News stories, including one in The New York Times, suggested protests. However, no actual meeting for violence happened.

This was just the start of the problems for the Belmont Syndicate.

Legal Challenges Begin

On Sunday, July 15, Satterwhite was arrested. The town marshal of Somerset arrested him for selling real estate without a license. This was a serious charge with a large fine. Six days later, Satterwhite went to court. His lawyer, Thomas Dawson, argued that Satterwhite owned the land. Therefore, he had the right to sell it without a license. Judge James Loughborough agreed and Satterwhite was found not guilty.

Right after this, the marshal arrested Satterwhite again. This time, it was for selling land on a Sunday. Again, Judge Loughborough found him not guilty.

The Syndicate's Struggle and End

Despite these wins, legal challenges continued. The Syndicate eventually had to sell the Belmont property. On April 17, 1907, the Evening Star reported that Dr. Zeno B. Babbitt planned to buy Belmont. Within a month, Satterwhite sold his shares to Ewell J. Nevitt. He did this without telling the other Syndicate members. He also made a new agreement with Babbitt.

Meanwhile, Dumas and his lawyer tried to get the lots released. They needed a special paper signed by Reeside and Donaldson. But Barnard, Johnson, Reeside, and Donaldson refused to sign. Because of the original purchase terms, other groups like the Chevy Chase Land Company could also stop the land's release.

On June 20, 1907, Dumas filed a lawsuit. He sued everyone involved in the Belmont land deals. For the next ten years, more lawsuits followed. But they didn't solve anything. The legal battles ended in a "stalemate" over 20 lots. A stalemate means neither side could win. The four men went their separate ways, and the Belmont Syndicate broke up.

Twenty years later, the Chevy Chase Land Company asked the court to remove Belmont from the county's property records. This happened after they reached an agreement with Michel O. Dumas. He was then a trustee for Howard University.

Related topics

Early African American suburbs

- Deanwood, Washington, D.C.

- Glenarden, Maryland, founded c. 1911

- Fairmount Heights, Maryland

- Lincoln, Maryland, founded 1908.

- Morgan Park, Baltimore

- Wilson Park, Baltimore

- Frederick Douglass Court, developed by Maggie L. Walker in Richmond, Virginia.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |