Biloxi wade-ins facts for kids

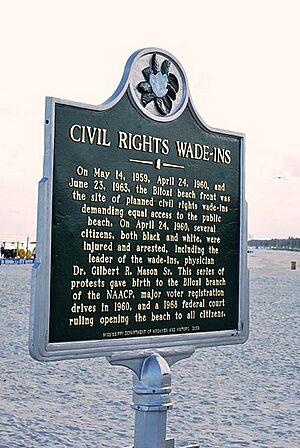

The Biloxi wade-ins were important protests that happened on the beaches of Biloxi, Mississippi. These events took place between 1959 and 1963, during the Civil Rights Movement. This was a time when many people worked to end unfair treatment and segregation (keeping people apart based on race) in the United States.

These protests were led by Dr. Gilbert R. Mason, Sr., a local doctor. His goal was to open up the city's 26 miles of beaches on the Mississippi Gulf Coast to everyone, no matter their race. This was a local effort, meaning it was organized by people in Biloxi, without much help from the larger state or national NAACP organization at first.

Before these protests, some people who owned homes near the beaches claimed the beaches were private property. But Dr. Mason and his supporters pointed out that the beaches were built in 1953 by the Army Corps of Engineers. This project used money from taxpayers, so they believed the beaches should be public and open to everyone. The new beaches brought more tourists to Biloxi, which helped the local economy.

However, local leaders wanted to keep the beaches segregated. They were supported by the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission. This state agency was created in 1956. It secretly watched citizens and planned ways to hurt the jobs or businesses of people who were involved in civil rights or were suspected of being activists. These secret activities were not known to the public for many decades. The commission's records were kept secret until 1998.

On April 24, 1960, police in Biloxi stood by as white groups attacked Black people on the beach. These attacks included older men, women, and children. White groups also attacked Black people throughout the city into the evening. During the day, ten times more Black people were arrested than white people, including Dr. Mason, who was injured. The mayor then set a curfew and finally told officers to stop the violence.

After this, African Americans in Biloxi quickly formed their own local chapter of the NAACP. That same year, they also started a big effort to help people register to vote. They wanted to get around state rules like poll taxes (fees to vote) and difficult literacy tests (tests to prove you could read and write). They held another wade-in in 1963. This time, the police protected them because a court hearing had been delayed. Finally, in 1967, a federal court ruled in favor of the Black residents, saying that the beaches were public and open to everyone.

Contents

The First Beach Protest

On May 14, 1959, Dr. Gilbert R. Mason, a Black doctor in Biloxi, went swimming at a local beach with friends and their children. This event is often called the first wade-in. A city policeman told them to leave, saying that "Negroes don't come to the sand beach."

Dr. Mason and his friend, Murray J. Saucier, Jr., went to the police station. They wanted to know what law they had broken. The police told them they couldn't show them the law until the next day. They just said that "only the public could use the beach." When they returned the next day, Biloxi mayor Laz Quave told them, "If you go back down there we're going to arrest you. That's all there is to it." Dr. Mason's 1959 protest was one of the first public challenges to racial segregation in Mississippi.

In June 1959, Dr. Felix H. Dunn, the first Black doctor in the county and a friend of Mason's, wrote to the Harrison County Board of Supervisors. He asked, "What laws, if any, prohibit the use of the beach facilities by Negro citizens?" The Board president replied that property owners along the beach owned both "the beach and water from the shore line extending out 1500 feet."

In October 1959, Dr. Mason, Dr. Dunn, and two other Black residents asked the board to allow "unrestrained use of the beach." A supervisor asked if they would be happy with using just a separate part of the beach. Dr. Mason said they would only be happy with access to the entire beach area.

The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission secretly investigated the people who signed the petition. They looked into their jobs, money history, and friends. They wanted to find ways to pressure them to stop their actions. One person who signed was fired from his job. Another man and his wife were fired by the white family they worked for. These two men then removed their names from the petition, hoping to get their jobs back. Since Dr. Mason and Dr. Dunn were more independent financially, they continued their efforts.

On April 17, 1960, Dr. Mason returned to the beach. He was arrested as a "repeat offender." Dr. Dunn was also taken to the station but was not charged. When news of his arrest spread, Dr. Mason learned that more people from the African-American community supported his actions.

The "Bloody Wade-in"

Dr. Mason led a second, larger protest a week later, on April 24, 1960. About 125 Black men, women, and children gathered on the beach. Violence started, led by white groups. This day became known as "Bloody Sunday" or "The Bloody Wade-in." Biloxi police allowed a group of white citizens to attack the protesters and did not stop the violence.

The New York Times newspaper called this event "The worst racial riot in Mississippi history." Shots were fired, and rocks were thrown by white people. Fighting happened in the streets throughout the entire weekend. Two white men and eight Black men were shot. Many people were hurt in fights, and four were seriously injured. Dr. Gilbert Mason was arrested and found guilty of disturbing the peace for his part in the protest.

On May 17, 1960, the U.S. Justice Department sued the city of Biloxi. They argued that the city was unfairly stopping African Americans from using the beaches, which were paid for with national funds. The city kept delaying the court hearing. Because of these delays, Biloxi's Black leaders decided to hold another protest in 1963. They hoped this would allow them to file a lawsuit in the Harrison County courts and get a faster decision.

The Final Protest

The last protest about beach access took place on June 23, 1963. This was two weeks after the murder of Medgar Evers, a leader for the NAACP in Mississippi. He had helped plan the Biloxi Wade-Ins. He had written a letter to Dr. Mason, saying, "if we are to receive a beating, let's receive it because we have done something, not because we have done nothing." The protest had been delayed so people could mourn Evers's death. During the protest, people placed black flags in the sand to remember him.

Many Black people were attacked during this protest. This included Wilmer B. McDaniel, who owned a local funeral home. Biloxi police arrested 71 protesters, and 68 of them were Black. More than 2,000 white residents held a counter-protest. They damaged and overturned Dr. Mason's car. However, the police stopped them from physically attacking the Black protesters.

It wasn't until 1967 that the beach access case was finally settled. The court ruled in favor of the U.S. Justice Department. It said that these were public beaches and should be open to all residents. In 1968, the entire 26-mile long beachfront was opened to all races for the very first time.

Lasting Impact

After "Bloody Sunday," Dr. Mason and other local activists organized during the week of April 25, 1960. They formed the first local branch of the NAACP in Biloxi. They also continued their efforts to help people. In 1960, they started a voter registration drive for African Americans. They wanted to help Black citizens overcome the unfair rules that had stopped them from voting for many years, like poll taxes and unfair literacy tests.

Remembering the Protests

In May 2009, the state of Mississippi put up a historical marker. This marker remembered the 50th anniversary of the first wade-in. Former Mississippi governor William Winter apologized for not doing more during those years of segregation. He said:

You didn't see this white face [on the beach with Mason] because white people, like me and many others, were intimidated by the massive forces of racial segregation. I have to admit I could not stand up to the pressure for being in public life in Mississippi and come out four-square for the elimination of segregation and for that I apologize today.

As part of this event, a section of U.S. Route 90 near Biloxi was renamed the "Dr. Gilbert Mason Sr. Memorial Highway."

In April 2010, another historical marker was placed at the Biloxi Lighthouse. This was a site of one of the wade-ins. It remembered the 50th anniversary of the protests.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |