Black Walnut (Clover, Virginia) facts for kids

|

Black Walnut Plantation

|

|

Black Walnut Manor House

|

|

| Location | 2091 Black Walnut Road, Clover, VA 24534 (VA 600, 850 ft. S of jct. with VA 778, in Halifax County, Virginia) |

|---|---|

| Area | 8 acres (3.2 ha) |

| Built | 1774 |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival, Georgian |

| NRHP reference No. | 91001597 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | October 29, 1991 |

Black Walnut is a very old plantation house and farm near Clover, Halifax County, Virginia. The main house was built in different parts starting around 1774. In the 1840s and 1850s, a large two-story addition was built. This made the house look like an "H" shape. Inside, it has a fancy Greek Revival style.

The property also has many other old buildings. These include a brick kitchen, a dairy, a wash-house, two smokehouses, and sheds. There is also a cool-storage building, a privy (an outdoor toilet), a stable, and a barn. You can also find a slave cabin, a corncrib (for storing corn), and machine sheds. A toolshed, a garage, and a schoolhouse from the late 1700s are also there. The family cemetery is on the land too.

At its busiest time, Black Walnut Plantation was one of the biggest and most successful farms in Halifax County. The only Civil War battle fought in Halifax County happened here. It was called the Battle of Staunton River Bridge in the summer of 1864. Confederate soldiers stayed here during the war. They also had up to 800 enslaved people working for them.

In September 1939, famous actress Mary Pickford visited Black Walnut. She was the Queen of the National Tobacco Festival.

Contents

Discovering Early History at Black Walnut

The Staunton River Battlefield Project helps us learn about the past. It is a team effort between Dr. James W. Jordan Archaeology Field School and the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. They study the Staunton River Battlefield State Park. At first, they looked at the Civil War battle from 1864.

Later, they found signs of an old Sappony Indian Village. This village was from the Late Woodland period. It was found at the Randy K. Wade Archeological Site.

So far, over 100,000 old items have been found here. Scientists used radiocarbon dating to find out the site was used from about A.D. 950 to 1425. Studies show that people lived there all year round, not just part-time. About 200 people are thought to have lived at the Wade Site. This research helps us understand how they lived. It shows what they ate and how their society was organized. It also teaches us about their burial customs and the environment they lived in.

One interesting thing is how different burial practices might show changes in their society. It suggests how their leaders changed over time. Another question is if the site was an island in the Staunton River. Future studies will keep looking for answers to these mysteries.

First Settlements in the 1700s

In 1741, a man named Richard Randolph got a large piece of land. It was 10,300 acres along the Staunton [Roanoke] River and two creeks. This land was in what was then Lunenburg County. When Halifax County was created in 1752, about 3,100 acres of Randolph's land became part of the new county.

In 1748, Richard gave this land to his son, John Randolph. The Randolph family lived in Henrico County. They owned several plantations there. Even though John Randolph did not live on this land, it was already called "Black Walnut Plantation." This means some buildings or farming had already started there.

William Sims Buys the Land in 1768

Twenty years later, in June 1768, John Randolph sold the 3,100-acre land to William Sims. William Sims lived in Charlotte County. The sales paper said the land was part of the "Black Walnut Plantation." It also mentioned a small plantation across from the Little Roanoke River.

William Sims and his brothers, David and Matthew, moved to Halifax County around 1770. William Sims grew tobacco as his main crop. He also grew other crops and raised animals. After owning the land for five years, William Sims sold his 3,100-acre property to his brother Matthew Sims. Matthew Sims settled on part of the land. In February 1774, he measured out 1,750 acres and sold it to his brother, David Sims.

Early Farming and Land Use (1770s–1800s)

Matthew Sims (1773–1790)

Matthew Sims kept some of the land for his home. He built his main house there. This house, from the 1770s, was likely a one-story or one-and-a-half-story building. It probably had four rooms and chimneys inside. The first known outbuilding at Black Walnut was a schoolhouse. It was a one-and-a-half-story wooden building with a steep metal roof. This old schoolhouse is still on the Black Walnut property today.

Matthew was active in the Episcopal church, like many important people in Halifax County. In 1783, Matthew and others were chosen to collect church payments in the western part of the county.

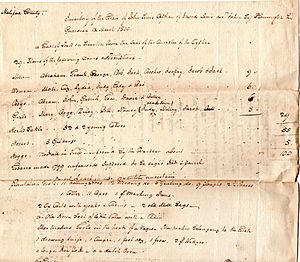

Matthew married Amey (Oney) May in 1774. Matthew died in 1790. He left behind his wife and nine children. Records from November 1790 show his property included 40 enslaved people. He also had personal items, crops, and farm animals. The crops included 200 barrels of corn and about 15,000 pounds of tobacco from 1790. He had 45 cattle and horses, and 13 hogs. Amey May Sims received 325 acres of land, which included the main house. The remaining enslaved people were divided among his children. For example, his son Matthew received four enslaved people. His daughter Lettie Sims received three enslaved people. This shows how enslaved people were treated as property.

David Sims (1774-1783)

David Sims lived on the 1,750 acres he bought from Matthew in 1774. David ran the plantation for ten years, until he died in 1783. In January 1774, he married Lettice May. David became an important farmer. He served as a church leader for Antrim Parish starting in 1782.

When David died in 1783, he left his wife and four children. His property was very large. It included 30 enslaved people, 70 cows, three oxen, 57 sheep, 59 hogs, and 11 horses. He also had household furniture and farming tools. Most of his land went to his son, John. It was held for John until 1803, when he was old enough to run the plantation. During this time, the plantation continued to grow tobacco. It also produced corn, beef, and pork. A record from 1797 listed 27 enslaved people, 39 cattle, 90 hogs, 45 young pigs, 35 geese, and several horses.

Growth and Changes (1800s-1890s)

John Sims (1803-1852)

John Sims, David Sims' son, helped Black Walnut become very successful. It was one of the richest farms in Halifax County. John Sims received his inheritance in 1803. This included 1,500 acres of land and 29 enslaved people. John Sims bought more land in the 1800s. He became one of the biggest landowners in the area. By 1850, only three other landowners had more land than him. John Sims ran the Black Walnut plantation for the next fifty years, until he died in 1852.

John Sims went to school at Hampden-Sydney. In 1809, he bought the 325-acre land and main house from his uncle Matthew's family. The next year, John Sims married Maria Wilson Clark. They lived at the Black Walnut plantation house. John and Maria Sims had four children. In 1815, their home was valued at $2,000.00.

The house had nice things inside. These included 8 window curtains, 1 carpet, and 12 chairs with gold leaf. There was also 1 piano, 1 sideboard, and 1 mahogany dresser. Other items were 1 dresser, 1 chest of drawers, 1 clock, and 2 silver trays. Maria Sims died in July 1822. John Sims spent the rest of his life raising his children and managing the large estate.

Black Walnut Plantation was at its best in the mid-1800s under John Sims. In 1850, the plantation had 1,000 acres of farmed land. It also had 1,200 acres of unfarmed land. John Sims' wealth grew because he had more enslaved people. Between 1820 and 1840, he increased his enslaved workforce from 77 to 137 people. By 1850, he had 150 enslaved people working for him.

Tobacco was the main crop sold for money. However, the plantation also grew other things. These included grain, raised animals, and dairy products. Another farm John Sims ran in the county was 337 acres. It grew corn, oats, tobacco, cotton, and produced butter.

The Black Walnut plantation complex grew to have many buildings. These included buildings for the family and for farming. The main house was the most important building. Buildings for the family, like a smokehouse, dairy, kitchen, and icehouse, were behind the main house. Slave quarters and farm buildings were further away from the main living area.

A formal garden with boxwood plants was south of the main house. A vegetable garden was to the northwest. Many native and decorative trees and bushes were planted around the grounds. The whole area was surrounded by woods. A family cemetery was northwest of the house.

John Sims' wealth was also shown by the big changes made to the main house. This happened in the early 1800s. The middle part of the house was made into a full two-story building. The house was changed again with a large two-story addition. This addition was connected by a middle section. This gave the house its "H" shape today. A tax record from 1848 showed the property's value went up because of these "improvements."

The house had two main sections with a hallway in the middle. These were joined by a central connecting part. The outside walls were made of wood siding. The roof was made of metal panels. Wooden decorations were on the front and back roof edges. Brick chimneys were on each end of the house. Small vents were in the attic. The front of the house had three parts and looked balanced. A one-story porch was in the center of the front. Windows with nine panes on top and nine on bottom were lined up across the front. The windows had wooden blinds. One-room sections were on either side of the back two-story part. A one-story porch stretched across the back.

Only a few of the plantation's outbuildings from this time still exist. These include a wash house/cool storage, a smokehouse, a slave cabin, a corn house, and a two-room brick kitchen. The kitchen is right behind the main house. All these buildings were made of wood and had steep roofs.

Two tobacco barns and another slave quarter still stand. They are southeast of the main house. These buildings were separate from the main family area. They were built with logs. In 1996, these buildings were in very bad condition.

William Howson Sims (1852-1890)

When John Sims died in 1852, his property was worth much more. It had grown to about 2,500 acres. Other property included 245 sheep, 12 oxen, 300 hogs, and 100 cattle. John Sims gave most of his land, including the main house, to his son, William Howson Sims. Smaller pieces of land went to his only living daughter, Maria Garrett, and his grandchildren. Maria Garrett received 47 enslaved people and small properties. His granddaughter, Elizabeth Coleman, received 46 enslaved people.

William Howson Sims managed the large Black Walnut plantation from 1852 until he died in 1890. William Howson went to school at Hampden-Sydney and became a lawyer. But he liked new farming methods more than law. So, he spent his time running his plantation. During his time, he bought more parts of the Black Walnut land. He also bought other land in Halifax County. William Howson also helped his aunt, Phoebe Howson Clark Bailey, run her plantation called "Oak Hill." Letters show that William H. Sims would ride his horse to her plantation to help her with her business.

In 1844, before he inherited Black Walnut, William Howson brought his wife, Sallie J. Wilson, and their four children to live at the main house. His daughters went to private school in Richmond in the 1860s. John Sims went to Virginia Military Institute (VMI) in 1867. William Bailey went to "Creek Side" school. William S. later graduated from Episcopal High School in Alexandria, Virginia.

In 1857, about 22 acres were sold to the Richmond and Danville Railroad Company. By this time, William Howson Sims owned 16 pieces of land in Halifax County. He also owned 116 enslaved people. He hired four managers to oversee his many lands. The 1860 Census shows William Howson Sims as a "planter." He owned land worth $57,000.00 and personal property worth $238,270.00.

Black Walnut During the Civil War

When the Civil War started, William H. Sims did not join the Confederate army. Instead, he kept running his plantation. He probably thought the war would be quick and successful. As the war went on, Sims helped the Confederate cause more. In March 1862, Sims was forced to join the army. He was supposed to be a private in Captain Moore's Company. William asked the Halifax County board for an exception. He was allowed to hire someone else to take his place. Sims had to pay $30.00 for his replacement's uniform. Sims wrote to his uncle about this news. In the same letter, he said that the Governor had called up the Richmond army to fight. At that time, Union soldiers were landing at Fort Monroe to march on Richmond. Sims was forced to join again the next year but was again exempted. Joseph H. Lambeth served as his replacement.

Later, the Confederate government stopped allowing people to hire replacements. William Sims then asked for an exemption again. While he waited for approval, he got ready to join the army as part of the Black Walnut Cavalry Company. But Sims did not join the cavalry. He stayed at Black Walnut.

In June 1864, the Battle of Staunton River Bridge happened. The Union army wanted to destroy the railroad bridge over the Staunton River. Confederate forces built defenses on Sims' side of the river and on the east bank. After the battle, a permanent Confederate army post was set up on Sims' property. It had both soldiers and 800 enslaved people working there.

William Sims was forced to join the army again in August 1864. He was officially assigned to the Confederate Subsistence Department. His job was to collect food in the Halifax area. He then sent it to the army.

According to the 1860 Agricultural Census, William Howson Sims had 1,800 acres of farmed land. He also had 2,000 acres of unfarmed land. During the Civil War, William Howson helped with the state's food shortages. He grew many different crops. These included tobacco, wheat, corn, oats, peas and beans, potatoes, grass seed, and hops. Horses, cows, oxen, sheep, and pigs were also raised on the plantation. Other products included wool, butter, and beeswax.

Throughout 1863, Sims continued to send farm goods to the Clover Depot of the Richmond and Danville (R&D) Railroad. By the next year, William Howson had to stop shipping goods from Clover Depot. This was because there were no railroad cars available for storage or transport. William Howson also lost several of his enslaved men. They were taken by the Confederate army. In October, Sims' managers were also forced to join the army.

To make things worse, the area had a drought in the summer of 1864. Sims tried to buy wheat for the army but had little success. In October, Sims collected some wheat for the army. In November 1864, Sims gave the army baled oats, fodder, and corn. On March 9, 1865, he provided straw.

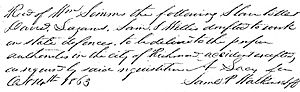

Sims also sold beef to the Confederate soldiers and enslaved laborers at the army post. Sims signed a pardon on August 2, 1865. Union soldiers continued to stay at Black Walnut Plantation after the war ended. However, this did not stop business. On April 17, 1865, Sims sold oats, flour, and corn.

After the War to Today

After the Civil War, William H. Sims sold some of his land. By 1870, the amount of farmed land dropped to 225 acres. He had 1,000 acres of unfarmed land. William H. likely rented land to farmers who paid him with crops or money. Many of the formerly enslaved people continued to live on the plantation. They worked as tenant farmers or paid laborers. Tobacco remained the main crop sold for money during this time. Even though less tobacco was grown than before, William Howson was still one of the top tobacco growers in his area. Other crops included wheat, corn, and oats. Many different animals were raised. These included horses, mules, oxen, cattle, sheep, and pigs.

By 1880, William H. had 245 acres of tilled land. He also had 150 acres of meadow and pasture, and 1,000 acres of wooded land. His farm animals were slightly fewer. He had seven horses, four mules, seven oxen, 40 sheep, and 35 pigs. Farm products were varied. They included eggs, butter, honey, and fruit. For the next 98 years, William H.'s family continued to run different parts of the plantation.

In 1978, Dr. William Randolph Watkins took over the property. He was the grandson of Maria Sims Garrett. When he died in 1997, his son Tucker Carrington Watkins IV lived at the plantation. He made many improvements. After Tucker died on October 6, 2012, his nephew John Payne Thrift III decided to sell the house's contents at auction. He also sold the 775-acre (314-hectare) property for $2,050,000 in 2014. No one in the family wanted to live there. This was the first time the house had been for sale since 1768.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |