Blowing engine facts for kids

A blowing engine is a huge machine that pushes a lot of air. Think of it like a giant pump for air! These engines are usually powered by steam or an internal combustion engine. They are connected to special cylinders that pump air.

Blowing engines are different from regular air compressors because they move a very large amount of air at a lower pressure. They are also much more powerful than a simple fan. Their main job is to provide a strong blast of air for furnaces, especially blast furnaces, which are used to melt metal like iron.

Contents

Early Blowing Engines: Water Power

The very first blowing engines were simple bellows powered by waterwheels. These were often found in special buildings called "blowing houses."

However, there was a problem. Places where metal ore was found (and where smelters were built) didn't always have a good river nearby for waterwheels. Also, droughts could stop the water supply, or the furnaces might need more air than the waterwheel could provide.

To solve this, people invented the "water-returning engine." This was one of the first ways steam engines were used to create power, not just to pump water out of mines. A steam pump would lift water up, and that water would then turn a waterwheel. The waterwheel would power the bellows. The water was then pumped back up to be used again. These early steam engines could only pump water; they couldn't directly power the bellows.

Some of the first working examples of these engines were set up in 1742 at Coalbrookdale in England. Later, in 1765, they were improved at the Carron Ironworks in Scotland.

Beam Blowing Engines

Early steam engines were often "beam engines." These engines had a large, rocking beam. Some just moved up and down, while others could also turn a large wheel. Both types were used as blowing engines. They worked by connecting an air-pumping cylinder to one end of the rocking beam, while the steam cylinder was on the other end.

For example, in 1821, an engineer named Joshua Field saw eight large beam engines at a company called Foster, Rastrick & Co. One of them was a 30-horsepower engine that powered a blowing cylinder. This cylinder was 5 feet wide and moved 6 feet with each stroke!

Later beam engines often had a large flywheel. This flywheel helped the engine run more smoothly. The air cylinder was still moved by the beam, and the flywheel just helped keep the motion steady.

A famous example of this type of engine is "David & Sampson." These are two beam engines that are now kept at the Blists Hill open-air museum in Ironbridge Gorge. Each engine has its own beam to drive an air cylinder, but they share one big flywheel. They are also known for their fancy, decorative arches. These engines worked for a very long time: 50 years providing air for furnaces, and then another 50 years as backup engines!

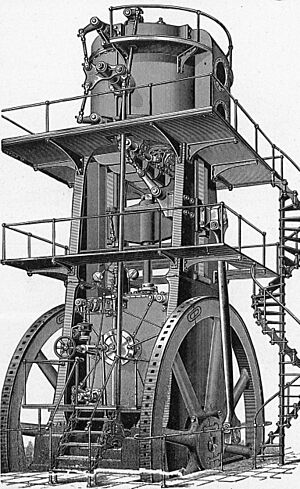

Vertical Blowing Engines

The large vertical blowing engine you see at the top of this article was built in the 1890s by a company called E. P. Allis Co. (which later became part of Allis-Chalmers). The steam cylinder at the bottom was about 42 inches (1.1 meters) wide, and the air cylinder at the top was about 84 inches (2.1 meters) wide. Both cylinders moved 60 inches (1.5 meters) up and down with each stroke.

This engine used a special type of valve system called "Reynolds-Corliss valve gear." This system helped the engine work faster and more efficiently. The air valves were also controlled by parts that moved with the engine's main shaft.

Like the beam engines, the main job of the flywheel on these vertical engines was to make the movement smooth. The steam piston pushed the air piston directly up and down. The flywheel shaft was located below the steam piston, with connecting rods driving downwards to make it a "return connecting rod engine."

Internal Combustion Blowing Engines

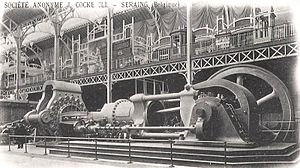

In the late 1800s, a new type of engine came along: the internal combustion gas engine. These engines could burn the gases produced by blast furnaces themselves! This was a huge step because it meant the furnaces didn't need extra fuel just to make steam for the blowing engines. It made the whole process much more efficient.

Companies like Bethlehem Steel started using this technology. These engines were often huge, with a single cylinder, and they burned the blast furnace gas. Famous makers of these engines included SA John Cockerill from Belgium and Körting from Germany.

Today, some people are trying to restore a few of these old engines. A few companies still make and install modern multi-cylinder internal combustion engines that can burn waste gases.

How Rotary Blowers Replaced Them

After World War II, when blast furnaces were updated, they started using diesel engines or electric motors to power their air supply. These newer power sources had a spinning (rotary) output, which worked perfectly with new types of centrifugal fans. These fans could handle the huge amounts of air needed.

Even though the older steam blowing engines were still used where they were already installed, very few new ones were built after the war. Many of these older plants began to close in the 1950s, and their numbers dropped a lot in Western countries during the 1970s. Because of this, blowing engines like the ones described here are quite rare today.

Surviving Examples Today

You can see examples of both a beam blowing engine and a vertical engine at the Blists Hill open-air museum in Ironbridge Gorge. The beam engines, named "David & Sampson," are even protected as important historical monuments.

An 1817 beam blowing engine, made by Boulton & Watt, is now a decoration in Birmingham, UK. It used to work at the Netherton ironworks. You can see it on a traffic island at the start of the A38(M) motorway.

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |