Boris Pahor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Boris Pahor

|

|

|---|---|

Pahor in 1958

|

|

| Born | 26 August 1913 Imperial Free City of Trieste, Cisleithania, Austria-Hungary (present-day Trieste, Italy) |

| Died | 30 May 2022 (aged 108) Trieste, Italy |

| Resting place | Trieste Cemetery |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Language |

|

| Alma mater | University of Padua |

| Notable works | Necropolis |

| Spouse | Radoslava Premrl (1921–2009) |

Boris Pahor (born August 26, 1913 – died May 30, 2022) was a famous Slovene writer from Trieste, Italy. He was known for writing about what it was like to be part of the Slovene minority in Italy before World War II. He also wrote about his experiences as a survivor of Nazi concentration camps.

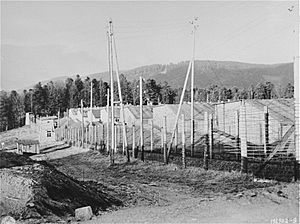

His most famous book is Necropolis. In this book, he revisits the Natzweiler-Struthof camp 20 years after he was held there. He was moved to several camps, including Dachau, Mittelbau-Dora, Harzungen, and finally Bergen-Belsen. He was freed from Bergen-Belsen on April 15, 1945.

Boris Pahor was a strong voice for the Slovene minority in Italy. This group faced tough times under Fascist Italianization, where their language and culture were suppressed. Even though he was part of the Slovene Partisans (a resistance group), he did not agree with communism.

He received many important awards. These include the Legion of Honour from France and the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art from Austria. He was even nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. He was the oldest living survivor of the Holocaust after September 2019.

Contents

Early Life and Challenges

Boris Pahor was born in Trieste on August 26, 1913. At that time, Trieste was a major port in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His family was part of the Slovene community there.

After World War I, Trieste became part of Italy. The Italian government, especially after Benito Mussolini came to power in 1922, started a policy called Fascist Italianization. This meant they tried to force everyone to become Italian. Slovene language and culture were forbidden.

In 1920, when Pahor was just seven years old, he saw Italian Black shirts burn down the Slovene Community Hall in Trieste. This was a very important building for the Slovene people. Later, all non-Italian languages, including Slovene, were banned in schools. Even family names were changed to sound Italian.

Pahor wrote about this difficult time in his books, like Trg Oberdan (Oberdan Square). This book is named after the square where the Slovene Community Hall once stood.

He studied at a Catholic seminary in Koper and later in Gorizia. He became dedicated to fighting against Fascism and all forms of totalitarianism. He believed in human values and community spirit. Even though Slovene was banned, he managed to publish his first stories in magazines in Ljubljana, which was then part of Yugoslavia.

In 1939, he met the Slovene poet Edvard Kocbek. Kocbek helped him improve his writing in standard Slovene. Pahor also connected with other Slovene thinkers in Trieste who were working secretly against Fascism.

Surviving Concentration Camps

In 1940, Pahor was called to join the Italian army. He fought in Libya and later worked as a military translator in Italy. He also studied Italian literature at the University of Padua.

When Italy surrendered in September 1943, Pahor returned to Trieste. The city was now under Nazi control. He decided to join the Slovene Partisans, a resistance group fighting against the Nazis.

Sadly, he was captured and handed over to the Nazis. He was sent to several concentration camps. These included Dachau, Natzweiler-Struthof, Mittelbau-Dora, Harzungen, and finally Bergen-Belsen. He was freed from Bergen-Belsen on April 15, 1945.

His time in these camps deeply affected him. It became the main inspiration for his writing. His work is often compared to other famous Holocaust survivors like Primo Levi. After the war, he spent time recovering in a French sanatorium until December 1946.

Standing Up for Freedom

Pahor returned to Trieste in 1946. He finished his studies at the University of Padua. He became good friends with Edvard Kocbek. Both of them were critical of the communist government in Yugoslavia.

Pahor strongly defended Kocbek's writings when the communist government attacked them. This caused him to break away from some leftist groups in Trieste. He became a supporter of democracy and freedom of thought.

In 1966, he started a journal called Zaliv (The Bay) with another writer, Alojz Rebula. This journal was published in Slovene in Trieste, outside the control of Yugoslavia's communist government. It became an important place for people who disagreed with the communist regime in Slovenia to share their ideas. Pahor stopped publishing the journal in 1990, after Slovenia had its first free elections.

From 1953 to 1975, Pahor taught Italian literature at a Slovene-language high school in Trieste. He also worked with an international group that promoted minority languages and cultures. This helped him see the rich variety of cultures in Europe.

In 1975, Pahor and Alojz Rebula published a book about Edvard Kocbek. Because of this, Pahor was banned from entering Yugoslavia for several years. He could only return in 1981 to attend Kocbek's funeral. His book Ta ocean strašnó odprt (This Ocean, So Terribly Open) helped bring Kocbek's work back into public view in Slovenia.

Later Life and Recognition

After 1990, Boris Pahor became widely recognized in Slovenia. In 1992, he received the Prešeren Award, which is Slovenia's highest cultural honor. In 2008, he received the Gold Order of Freedom. He also became a full member of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts in 2009.

In 2010, a documentary film called Trmasti spomin (The Stubborn Memory) was shown on Slovenian TV. It featured many famous people talking about Pahor's importance.

He was also nominated to be an honorary citizen of Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia. However, Pahor refused this honor. He felt that the Slovene minority in Italy had not received enough support from Slovenian political leaders during the time of Fascist Italianization.

International Recognition

It took some time for Boris Pahor to become well-known outside of Slovenia. A Slovene philosopher living in France predicted that Italy would only recognize Pahor after France and Germany did. This turned out to be true. His books were first translated into French and German. Only after that, in 2007, did Italian publishers start to show interest in his work.

In 2008, he was interviewed for the first time on RAI, Italy's national public television. This was a big moment for his recognition in Italy.

In 2009, Pahor refused an award from the mayor of Trieste. The mayor did not mention Fascism alongside Nazism and communism. Pahor believed it was important to acknowledge all forms of totalitarianism. Many Italian intellectuals supported his decision.

International Awards

In 2007, the French government gave Pahor the Legion of Honour, a very high award. In 2009, he received the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art from the Austrian government. He also received the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic from Italy.

Death

Boris Pahor passed away at his home in Trieste, Italy, on May 30, 2022. He was 108 years old. He was buried in the Trieste cemetery a week later.

Theatre Adaptation

In 2010, Pahor's novel Necropolis was turned into a play. It was performed at the Teatro Verdi in Trieste. This event was seen as a "historical step" in improving relations between Italians and Slovenes in Trieste. After the performance, Pahor said he finally felt like a first-class citizen of Trieste.

Literary Achievements

Boris Pahor's work became well-known in Yugoslavia starting in the 1960s. However, the Slovenian communist government did not fully recognize him because they saw him as a challenging figure. Despite this, he became a very important role model for a new generation of Slovene writers.

His main works include Vila ob jezeru (A Villa by the Lake) and Mesto v zalivu (The City in the Bay). His most famous is Nekropola (Pilgrim among the Shadows). He also wrote a series of books about Trieste and the Slovene minority.

Several of his books have been translated into German, French, Italian, and many other languages, allowing his powerful stories to reach readers worldwide.

Selected Works (translated and published internationally)

- 1955 Vila ob jezeru (The Villa by the Lake), a novel

- 1955 Mesto v zalivu (The City in the Bay), a novel

- 1959 Kres v pristanu (Bonfire in the Port), short stories

- 1967 Nekropola (Necropolis or Pilgrim Among the Shadows), a novel

- 1975 Zatemnitev (Obscuration or Dark Days), a novel

- 1978 Spopad s pomladjo (A Difficult Spring), a novel

- 1984 V labirintu (In the Labyrinth), a novel

- 1999 Zibelka sveta (The Cradle of the World or The Golden Gate), a novel

- 2006 Trg Oberdan (Oberdan Square), a novel

See also

In Spanish: Boris Pahor para niños

In Spanish: Boris Pahor para niños

- The Holocaust in art and literature

- Slovenian literature