British Engineerium facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The British Engineerium |

|

|---|---|

The former boiler house and engine rooms from the southeast

|

|

| Location | The Droveway, West Blatchington, Brighton and Hove, East Sussex, United Kingdom BN3 7QA |

| Built | 1866 |

| Built for | Brighton Hove and Preston Constant Service Water Supply Company |

| Architectural style(s) | High Victorian Gothic |

|

Listed Building – Grade II*

|

|

| Official name: Boiler and Engine House at British Engineerium; Chimney 2 metres south of the Boiler and Engine House at British Engineerium |

|

| Designated | 7 June 1971 |

| Reference no. | 1187600; 1292285 |

|

Listed Building – Grade II

|

|

| Official name: Cooling Pond and Leat at British Engineerium; Former Coal Shed at British Engineerium; Walls enclosing British Engineerium |

|

| Designated | 7 June 1971 |

| Reference no. | 1187601; 1210170; 1298616 |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

The British Engineerium is a special museum in Hove, East Sussex, that shows off amazing engineering and steam power. It's located inside the Goldstone Pumping Station, which is a group of beautiful buildings built starting in 1866. These buildings are designed in a style called High Victorian Gothic, which means they look grand and decorative.

For over a hundred years, the Goldstone Pumping Station provided water to the local towns. It was a very important place! However, it closed to the public in 2006. In March 2018, the whole complex was put up for sale. As of August 2025, it is still closed while more restoration work is being done.

At its biggest, between 1884 and 1952, the complex had two boiler houses with powerful steam engines, a tall chimney, and other important parts like coal storage, a workshop, and a cooling pond. It was built on top of a natural chalk area that held lots of water. This allowed it to supply huge amounts of water to the fast-growing towns of Hove and Brighton.

Over time, new ways to get water were found, and more modern equipment was installed. Because of this, the pumping station became less important. By 1971, the water department decided to close it and even thought about tearing it down. But then, an expert in old industrial sites, Jonathan Minns, stepped in. He offered to fix up the buildings and machines if he could lease the site. A special group was formed to help him.

The people who worked and volunteered at the Engineerium became very skilled. They even helped start other museums and fix up old machines around the world. They also taught young people how to preserve engineering history. Later, another enthusiast bought the complex. It is currently being restored and expanded, so it's not open to visitors right now.

The buildings themselves are famous in Hove. They show how people in the 1800s believed that even useful buildings should be beautiful, not boring! They have colorful bricks, fancy decorations, and detailed windows. Even the 95-foot-tall chimney looks like a grand bell tower. English Heritage, a group that protects important places, has listed the complex as historically and architecturally important. This means it's a very special site!

Besides the restored pumping station equipment, the Engineerium has many other cool exhibits. Soon after it first opened, it had over 1,500 items on display. These included an old horse-drawn fire engine, big traction engines, early motorcycles, Victorian household items, and old tools. A large French-built steam engine from 1859 is one of the main attractions. Before it closed in 2006, the Engineerium used its exhibits to teach people about industrial history. It was even called "the world's only center for the teaching of engineering conservation." For many years, the bigger machines were fully working and could be seen steaming on weekends.

Contents

History of the Engineerium

Brighton and Hove are towns on the coast of England. They were built on top of a huge natural underground water source made of chalk. This meant there was always a good supply of clean water from this natural reservoir. In the early days, many wells were dug to get this water.

However, Brighton grew very quickly in the 1700s and early 1800s, and Hove grew too. This put a lot of pressure on the local authorities to find more water and better ways to deliver it. The wells started to get dirty from sewage, and some even had to be closed because they were so polluted. This made the water problem even worse.

The first local water company was started in 1834. It built a waterworks and provided piped water for two hours a day to a few wealthy homes. This facility used two 20-horsepower steam engines.

More Water Needed

By the 1850s, even more water was needed because the population kept growing. The old waterworks only provided water sometimes, and wells were the only other option. In 1853, a new company was formed to bring a large, steady water supply to Brighton, Hove, and nearby villages. This new company bought the old one in 1854.

By 1872, when the city of Brighton took over the company, it was pumping 2.6 million gallons of water every day. This water went to 18,000 houses in Brighton, Hove, and surrounding villages.

The company hired a famous engineer named Thomas Hawksley to find a good spot for a new pumping station. Hawksley built more waterworks than almost anyone else in his time. In 1858, he suggested a chalk valley called Goldstone Bottom, just outside Hove. Test wells were dug, and they confirmed it was a great spot.

The company bought the land in 1862 and got permission to build the pumping station in 1865. The old waterworks was having pollution problems, and even new reservoirs weren't enough to meet the demand for water.

Building the Goldstone Pumping Station

Construction happened in 1866, and the Goldstone Pumping Station opened that same year. It was run by the Brighton, Hove and Preston Constant Water Service Company until Brighton Corporation took over.

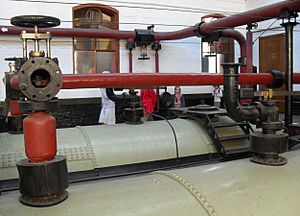

Originally, the complex had a boiler house, an engine room next to it, coal cellars, and a chimney. The chimney was described as "truly monumental" because it was so impressive. All these buildings were made of colorful bricks. The engine room held a 120-horsepower steam engine, which was called the "Number 1 Engine." It got its power from three large boilers and could pump up to 130,000 gallons of water per hour.

In 1872, Brighton Corporation took over all the water facilities in the area. They created a new group called the Brighton Water Corporation to manage them.

Expanding the Pumping Station

Because the demand for water kept growing, the corporation decided to expand the pumping station in 1876. They added a second engine room and a separate shed for storing coal. They also built a workshop with tools like a forge and a lathe. This workshop even had its own steam engine.

The new engine house got the "Number 2 Engine," which was a 250-horsepower steam engine. It could pump 150,000 gallons of water per hour and was powered by three more boilers. The Mayor of Brighton, Henry Abbey, started this engine for the first time on October 26, 1876. Tunnels were built underground to connect the new coal shed, the workshop, and the boiler room. Coal trucks used these tunnels.

The next expansion happened in 1884. A cooling pond and an artificial waterway (called a leat) were built behind the pumping station. A huge underground reservoir, holding 1.5 million gallons of water, was also built. This reservoir stretched for half a mile from the complex. Brighton Water Corporation spent a lot of money on this work. The reservoirs were always full because water flowed in from natural cracks in the chalk.

Decline and Rescue Efforts

In the years between World War I and World War II, the area around the pumping station became very built up. So, from 1937, the water was treated with ozone to make it clean. In 1934, the boilers for the Number 2 Engine were replaced with four new, more powerful ones.

However, the pumping station soon started to decline. Electric pumps became available in the 1940s. One was installed in the Number 1 Engine room, and that engine was stopped. The new boilers for Number 2 Engine were only used for 18 years. Number 2 Engine was taken out of service in 1952. Many new pumping stations had been built, and old water sources were brought back into use. The Goldstone Pumping Station was seen as old-fashioned and no longer needed. In 1971, the corporation announced plans to build a small electric pump house on the site and tear down the old 19th-century buildings and equipment.

Jonathan Minns, an expert in steam and engineering from London, immediately tried to save the buildings and their contents. He asked the Historic Buildings Council for England (now English Heritage) to give the buildings special "listed status." This status was granted on June 17, 1971. The next year, the government issued a preservation order, which stopped the buildings from being torn down or changed too much.

Minns got the lease for the complex in 1974. He planned to restore it and create an industrial museum and educational center. He also set up a trust to run it. At this time, the ownership of water systems in England changed. Brighton Water Corporation became part of the Southern Water Authority, which then gave the lease to Minns.

Restoration and Reopening

Minns started with only £350, but more money soon came in from grants and donations. The Southern Water Authority gave the trust £22,000, and the government gave £40,000. In 1975, the trust received the largest historic buildings grant ever given in Sussex up to that point.

In October 1975, Minns and eight volunteers began to restore the complex and its machines, which were in very bad shape. The boiler house and Number 2 Engine were the main focus. But first, the workshop had to be fixed so its tools could be used for the other repairs.

The boiler house and Number 2 Engine were in terrible condition. The roof was broken, metal parts were rusted, and moss was growing everywhere. Number 2 Engine hadn't been used since 1954. It had to be taken apart and rebuilt while the building was being fixed around it. Every moving part was cleaned by hand. The outside was repainted in its original color after the old paint was found under layers of mold and rust.

The eight men worked for about six months on these tasks. Number 2 Engine was successfully started again on March 14, 1976, after the two fixed boilers were checked by safety officials. The other two boilers were left as they were.

The complex first opened to the public on Good Friday in 1976. The official reopening was on October 26, 1976, exactly 100 years after Number 2 Engine was first started. By this time, the coal storage area had been turned into an exhibition and educational space. At first, it was called the Brighton and Hove Engineerium. It got its current name, the British Engineerium, on May 30, 1981.

By 1981, about 1,500 exhibits were on display. The boilers and Number 2 Engine were started up every weekend. Running the Engineerium and paying its 18 employees cost about £250,000 per year. Even though the Southern Water Authority, which still owned the site, paid for improvements in 1983, and grants came from local councils, there was no money from the national government. However, the Engineerium was recognized as a world leader in industrial heritage. Its employees helped set up or fix more than 20 similar places around the world.

In 1993, the Duke of Kent visited the center. This visit happened at the same time as a request for £4 million to expand the exhibition space and workshop. Minns also tried to get a grant from the National Lottery but was not successful. However, Vodafone paid to put a mobile phone mast on the chimney.

Recent Years

Ongoing money problems caused the Engineerium to close in 2006. The complex and its contents were put up for auction. Just before the auction, a local businessman named Mike Holland offered £2 million for the buildings and over £1 million for the contents. This offer was accepted, and on May 10, 2006, the Engineerium's assets became Mike Holland's property.

The Engineerium stayed closed while its new owner invested in improvements and expansions. In February 2010, he said he expected it to reopen within a year. On October 10, 2010, it opened for one day to raise money for charity. The Number 2 Engine was shown working, and many steam engines and other exhibits were on display.

In August 2011, the local council approved plans for some renovation and remodeling work, including an extension. Engineers found that part of the building was in poor condition. In January 2012, another request was made to get permission to tear down and rebuild part of the machine room. General restoration work began in October 2012, helped by a second open day.

Jonathan Minns passed away on October 13, 2013, at age 75. Two years later, a fire damaged the chimney. In 2017, due to changes in ownership, the complex was put up for sale in March 2018.

Architecture and Design

Historians have called the Engineerium an "unusually fine asset" and a "splendid example of Victorian industrial engineering." The buildings have very detailed and colorful brickwork. The 95-foot-tall chimney to the south is also beautifully designed and is a well-known landmark in Hove.

Both the buildings and the machines inside show how people in the Victorian era believed that every object and building, no matter how ordinary, should be decorated in a fancy and grand way.

Main Buildings

On the main buildings, the walls are made of bands of red, yellow, and purplish-blue bricks. They have decorative layers and caps on top. The ground floor has red bricks that look rough and textured. The cast-iron windows are set in round-arched openings. A decorative band of red and black bricks runs around the whole building above the windows.

The slate roof has flat-topped gables (the triangular parts of a wall at the end of a pitched roof) above the top of each engine room. The two engine rooms have two floors and three sections with three windows each. They are on either side of the single-story boiler room, which also has three sections. The left and right sections are set back slightly. All the windows are similar to those in the engine rooms.

The Chimney

The chimney stands about 7 feet south of the engine rooms and boiler house. It's a rectangular structure that looks like a bell tower. It has a textured base with a sloped bottom part. Above this is a decorative molding. The chimney itself gets slightly narrower as it goes up. It has tall arched panels on each side, creating slight indents. A decorative band runs all the way around, connecting these panels. The brickwork uses the same colors and details as the other buildings.

Other Structures

The former coal shed, which is now the exhibition hall, and its attached workshops are made of red and brown bricks. They have caps on the walls and a shallow slate roof. The workshops are attached to the back of the coal shed, making the building shaped like an "L." Because the land slopes, the building has one story at the front and a second lower story towards the back. The front has three arched entrances.

Behind the main complex, there's a cooling pond that measures 1,100 square feet. It has a leat (an artificial waterway) around three sides. Small walls of red brick and terracotta surround it. Pipes connect the leat to the boiler house. Hot water flows from the boiler house into the cooling pond, where it cools down. Then, the cold water is sent back to be used in the boilers.

Tall walls made of flint and brick, built in 1866, surround the complex on all sides. Small flints laid in rows make up most of the walls on three sides. Other parts have red brickwork with flints set into them. The main entrance has red-brick pillars with specially shaped flintwork. There are also iron railings and gates with the fleur-de-lis symbol (a stylized lily or iris). The walls have recessed areas on the inside and outside. One on the outside of the south wall has a drinking fountain with a panel asking people to "commit no nuisance." Flints are common in this area. So many were found when the pumping station was built that the builders made them into a deliberately old-looking decorative structure on the southwest corner of the engine rooms.

Exhibits and Collections

The Engineerium has hundreds of exhibits that tell the story of engineering and steam power. Many of these are displayed in the exhibition hall, which used to be the coal storage shed.

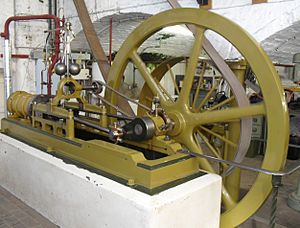

The main attraction in the hall is a Corliss steam engine built in France in 1859. An American inventor named George Henry Corliss created this design in 1849. His invention greatly improved how efficient horizontal steam engines were. The Engineerium's engine was put together in 1859 by a company in Lille, France. It was shown at a big exhibition in Paris in 1889, where it won first prize. After that, it was used for over 50 years at a hospital in France. Jonathan Minns bought it, took it apart, brought it to the Engineerium, and put it back together in 1975. This engine can create 91 horsepower. Its 13-foot, 4-ton flywheel turns 80 times a minute, and the whole machine weighs 16 tons!

The Engineerium also has a horse-drawn fire engine from 1890. This vehicle was originally owned by the local authority in Barnstaple, Devon. The museum's employees bought and restored it. It's a steam engine with two cylinders. A steam traction engine built in 1886 has also been restored. There are also many old motorcycles on display. The oldest is an Ariel Motorcycles vehicle from 1915.

In other parts of the complex, you can see smaller steam engines, along with Victorian tools and household items like old stoves. Much of the equipment in the workshop is original, such as the main forge and a heavy-duty metal lathe. The single-cylinder steam engine used to power the tools in the workshop was already several years old when the Goldstone Pumping Station got it in 1875.

From the very beginning, the main goal of the exhibits was to show and explain the history of engineering and British industry. This was done by fixing up the pumping station's original equipment and by getting other items connected to famous industrial pioneers like James Watt and George Stephenson. For example, there is a model of Stephenson's Locomotion No 1 engine.

Heritage Status

When Jonathan Minns found out in 1971 that the complex might be torn down, he successfully asked the Historic Buildings Council for England (now English Heritage) to give it special "listed status." This organization granted listed status to five main structures on June 7, 1971.

The boiler rooms and engine house were jointly listed at Grade II*. The free-standing chimney also received Grade II* status. Three more structures were listed at Grade II: the cooling pond and leat, the coal storage shed, and the flint and brick walls around the complex.

Grade II* is the second-highest of the three levels for listed buildings. Buildings with this status are considered "particularly important" and "of more than special interest." As of February 2001, the boiler house and chimney were two of the 70 Grade II*-listed buildings in Brighton and Hove. Grade II is the lowest status, given to "nationally important buildings of special interest."

In 1982, an 8.89-acre area that included the entire Engineerium complex became a conservation area. This means it's a place with special historical or architectural importance that is protected.

See also

- Brede Waterworks

- British Engineering Excellence Awards

- Grade II* listed buildings in Brighton and Hove

- Grade II listed buildings in Brighton and Hove: A–B

- List of conservation areas in Brighton and Hove