British expedition to Abyssinia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids British Expedition to Abyssinia |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The burning fortress of Magdala |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

≈4,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

||||||

The British Expedition to Abyssinia was a rescue mission and a trip to punish someone. It happened in 1868. The British army went to the Ethiopian Empire, which was also called Abyssinia back then.

Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia (sometimes called Theodore) had captured some missionaries and two British government officials. He did this because he wanted the British government to send him military help. When they didn't, he got angry.

In response, the British sent a large army. They had to travel hundreds of kilometers across mountains with no roads. The leader of the expedition, General Robert Napier, managed to overcome these huge challenges. His army captured the Ethiopian capital and freed all the prisoners.

One historian, Harold G. Marcus, called this event "one of the most expensive affairs of honour in history."

Contents

Why the Expedition Happened

By 1862, Emperor Tewodros was having a tough time ruling. Many parts of Ethiopia were rebelling against him. He only controlled a small area around his fortress at Magdala. He was always fighting different groups. Also, Ethiopia was being threatened by other countries like the Ottoman Turks and Egyptians.

Tewodros wrote letters to powerful countries like Russia, France, and Britain, asking for help. He hoped to get military support and new technology. The French government was the only one that replied, but they had their own demands.

Tewodros's letter to Queen Victoria of Britain asked for help because they were both Christian rulers facing Muslim expansion. However, Britain had other interests. They wanted to protect their trade routes to India and get cotton from Egypt and Sudan. Helping Tewodros might upset the Ottoman Empire, which Britain saw as a useful buffer against Russia. So, the British Foreign Office didn't want to support Tewodros. His letter was kept but never answered.

The Hostages

The first European to meet Tewodros after this silence was Henry Aaron Stern, a British missionary. Stern had written a book that mentioned the Emperor's humble beginnings. Even though it wasn't meant to be rude, Tewodros was very proud of his royal family history. He became furious. Stern's servants were beaten to death, and Stern himself, along with his assistant, Mr. Rosenthal, were chained and treated badly.

The British consul, Charles Duncan Cameron, and a group of missionaries tried to get them released. For a while, it seemed like it might work. But on January 2, 1864, Cameron and his staff were also captured and chained. Soon after, Tewodros ordered most of the Europeans in his camp to be chained too.

The British government sent Hormuzd Rassam, an Assyrian Christian, to try and solve the problem. But Rassam's journey was delayed, and he didn't reach Tewodros until January 1866. At first, it looked like Rassam might succeed. The Emperor treated him well and even sent the other hostages to Rassam's camp.

However, around this time, another person named Charles Tilstone Beke arrived. He sent letters from the hostages' families to Tewodros, asking for their release. This made Tewodros suspicious. Rassam later wrote that this was when the Emperor's behavior towards him changed.

Emperor Tewodros became more and more unpredictable. He would be friendly one moment and then suddenly angry and violent. In the end, Rassam himself was made a prisoner. One of the missionaries was sent to deliver the news and Tewodros's latest demands in June 1866. The Emperor eventually moved all his European prisoners to his fortress on Magdala. He continued to talk with the British until Queen Victoria decided to send a military expedition to rescue them on August 21, 1867.

The Campaign

Planning the Mission

One historian, Alan Moorehead, said there had never been a colonial campaign quite like this one. It was a huge and difficult task. For hundreds of years, Ethiopia had never been invaded. The rough land alone could have caused the mission to fail.

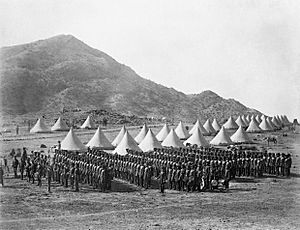

The job was given to the Bombay Army, and Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Napier was put in charge. This was unusual because it was the first time an officer from the Corps of Royal Engineers led a campaign. But it was a smart choice, as engineering skills were key to success.

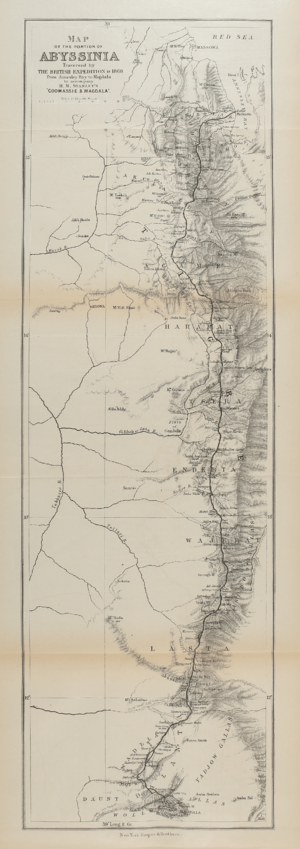

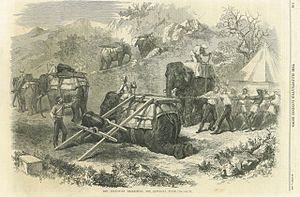

The British carefully gathered information about Ethiopia. They figured out how many soldiers and supplies they would need. For example, 44 trained elephants were brought from India to carry heavy guns. Mules and camels were hired from all over to carry lighter gear. A railway was built across the flat coastal land, and large piers and warehouses were set up at the landing spot.

The British knew they needed a constant supply of food for their men and animals. So, they decided not to steal supplies. Instead, they paid for everything. They brought a lot of Maria Theresa Thalers, which was the common money in Ethiopia at the time.

The force included 13,000 British and Indian soldiers, 26,000 helpers, and over 40,000 animals. Many journalists, including Henry Morton Stanley, and other observers, artists, and photographers also came along. The whole force sailed from Bombay on more than 280 ships.

The first group of engineers landed at Zula on the Red Sea in mid-October 1867. They started building a port. Within a month, they had built a long pier. A railway was also built inland. At the same time, another group built a 63-mile road to Senafe for the elephants and carts. They needed a lot of water. Wells were dug, which became known as "Abyssinian wells" because they were so good at finding water.

From Senafe, Napier sent two letters. One was to Emperor Tewodros, demanding the hostages be freed. The other was to the people of Ethiopia, saying that the British were only there to free the prisoners and would only fight those who opposed them. Napier arrived at Zula on January 2, 1868, and left for Senafe on January 25.

The March to Magdala

It took the British army three months to travel over 400 miles of mountains to reach Tewodros's fortress at Magdala. At Antalo, Napier met with Dajamach Kassai (who later became Emperor Yohannes IV). Napier gained his support, which was very important. Without help or at least neutrality from the local people, the British would have had a much harder time reaching Magdala. On March 17, the army reached Lake Ashangi, about 100 miles from their goal. Here, they cut their food rations in half to lighten their loads.

By this time, Emperor Tewodros's power was already fading. By 1867, his army had shrunk to only 10,000 men because many had left him. One historian noted that Napier spent about £9,000,000 to defeat a ruler who had only a few thousand troops and was no longer truly in charge of Ethiopia.

The British also got help from local leaders and princes. These agreements protected their march and provided food and supplies. The three most powerful Ethiopian princes in the north promised to help the British army. This turned what looked like an invasion into a fight for just one mountain fortress, defended by a few thousand warriors working for an unpopular ruler. The British also got two Oromo Queens to block any escape routes from Magdala.

Tewodros's Last Stand

While the British marched south, Tewodros moved from the west towards Magdala. He brought his cannons, including a huge one called Sebastopol, which European missionaries had built for him. Tewodros wanted to reach Magdala before the British. Even though he started earlier and had a shorter distance, he only arrived ten days before his enemies. Tewodros's journey was harder because he had to travel through unfriendly areas and fight off attacks. He also had more trouble feeding his army and moving his heavy cannons than Napier did. Most importantly, Tewodros couldn't even trust the 4,000 soldiers who were still with him. They might leave him at any moment.

On February 17, Tewodros showed his poor leadership skills again. After people from Delanta surrendered to him, he asked why they waited so long. When they said rebellious groups stopped them, he ordered his soldiers to rob them. The people fought back bravely, killing many of his soldiers. This made other groups who were coming to surrender turn back.

The British Arrive

On April 9, the first British soldiers reached the Bashilo River. The next morning, Good Friday, they crossed the river.

That afternoon, the important Battle of Magdala began outside the fortress. The British had to pass through a plateau called Arogye, which was the only way to Magdala. Thousands of Ethiopian soldiers, with about 30 cannons, were waiting there. The British didn't expect the Ethiopians to attack them and were still getting ready.

However, Tewodros ordered an attack. Thousands of soldiers, many with only spears, charged the British. The British quickly got into position and fired their guns, rockets, and cannons. One captain noted how terrible the damage was. During the fight, a British unit captured some of the Ethiopian cannons. After a quick 90-minute battle, the defeated Ethiopians went back to Magdala.

About 700 to 800 Ethiopian soldiers were killed, and 1,200 to 1,500 were wounded. On the British side, only two men were fatally wounded, nine seriously wounded, and nine lightly wounded. The battle at Arogye was much bloodier and more important than the siege of Magdala the next day.

Siege of Magdala

After the battle, the British moved towards Magdala the next day. As they got closer, Tewodros released two hostages to offer terms. Napier demanded that all hostages be released and that Tewodros surrender without conditions. Tewodros refused to surrender completely, but he did release the European hostages over the next two days. Sadly, the native hostages were treated cruelly before being thrown off the cliff around the fortress.

The British continued their attack on April 13 and began to surround the fortress of Magdala. The attack started with bombs, rockets, and cannon fire. British soldiers then fired their rifles to cover the engineers. The engineers blew up the fortress gates at 4 PM. British soldiers rushed in and fought their way to the second gate. They took the second gate and found Tewodros dead inside. He had taken his own life. When his death was announced, the fighting stopped. One person said that by choosing to die rather than be captured, Tewodros became a symbol of Ethiopian independence.

Tewodros's body was burned, and his ashes were buried in a local church by priests. Soldiers from the 33rd Regiment guarded the church but also looted it. They took gold, silver, brass crosses, and other valuable items.

The battle for Magdala itself had few casualties. The British bombardment killed about 20 Ethiopian soldiers and civilians and wounded about 120. Another 45 Ethiopians were killed by rifle fire during the attack. The British had only ten seriously wounded and five lightly wounded soldiers. These numbers were much lower than the previous day's battle at Arogye, which was the main fight of the campaign.

Before leaving Magdala, Sir Robert Napier ordered Tewodros's cannons to be destroyed. He also allowed his troops to loot and burn the fortress, including its churches, as a punishment. The troops collected many historical and religious items, which were taken back to Britain. Many of these can now be seen in the British Library and the British Museum. It took 15 elephants and almost 200 mules to carry all the stolen goods.

Aftermath

Magdala was in the land of the Muslim Oromo tribes, who had lost it to Tewodros some years earlier. Two rival Oromo queens, Werkait and Mostiat, had helped the British and wanted control of the fortress as a reward. Napier preferred to give Magdala to the Christian ruler of Lasta, Wagshum Gobeze. He hoped Gobeze would stop the Oromos and take care of the 30,000 Christian refugees from Tewodros's camp. But Gobeze was more interested in Tewodros's cannons, and the two Oromo queens couldn't agree. So, Napier decided to destroy the fortress.

After destroying Magdala, the British began their journey back to Zula. It was an impressive procession, but the army soon realized they hadn't earned any thanks in Ethiopia. They were seen as just another fighting group. Now that they were leaving, they were a target for attacks. At Senafe, the British rewarded Ras Kassai, Yohannes IV, for his help. They gave him many supplies, including cannons, rifles, and ammunition. These gifts later helped him become Emperor over his rivals.

At Zula, Napier asked Captain Charles Goodfellow to dig for artifacts in Adulis, an ancient port city. They found pottery, coins, and stone columns. This was the first time an archaeological dig happened in Adulis, an important ancient African trading hub.

By June 2, the base camp was taken down. The soldiers and freed hostages got on ships. Napier himself left on June 10, sailing for England through the Suez Canal.

Interestingly, many of the freed hostages were not happy about leaving Ethiopia. They felt they no longer belonged in Europe and wouldn't be able to start new lives there. Many of them eventually returned to Ethiopia.

In London, Napier was given the title Baron Napier of Magdala to honor his success. He also received another high honor. At Gibraltar, where he later served as governor, there is a battery (a place for cannons) named after him.

One soldier from the expedition, John Kirkham, stayed in Ethiopia. He became an advisor to Yohannes IV. Kirkham helped train Ethiopian troops to fight like Western armies. These troops played a big part in defeating Yohannes's rival, Wagshum Gobeze, in the Battle of Assam in 1871. Kirkham lost his British citizenship by serving Yohannes. This caused problems later when he was captured by Egyptian forces. He died in prison in 1876.

Ethiopian Politics After the Expedition

Before he died, Tewodros had asked his wife, Empress Tiruwork Wube, to put his son, Prince Alemayehu, under British protection. He feared his son would be killed by anyone trying to become the next emperor. So, Alemayehu was taken to London and met Queen Victoria, who liked the young boy. Alemayehu later studied at famous British schools. However, both the Queen and Napier worried about the prince, who became lonely and sad. In 1879, he died at age 19. He was buried near the royal chapel in Windsor, and Queen Victoria placed a plaque in his memory.

After the British left, there was a fight for Tewodros's throne in Ethiopia from 1868 to 1872. Eventually, Dajamach Kassai of Tigray won. The British weapons he received from the Magdala expedition helped him greatly. In July 1871, he won the Battle of Assam, even though he had fewer troops than his rival, Wagshum Gobeze. Kassai crowned himself Emperor of Ethiopia, taking the name Yohannes IV.

Battle Honor

Because the expedition was so successful, a special honor called "Abyssinia" was given to British Indian Army units that took part in the campaign.

Looted Objects

The British Museum sent a staff member with the expedition. After the Magdala expedition, many looted objects, cultural items, and artworks ended up in museums, private collections, and with ordinary soldiers. Most of the books and old writings went to the British Museum or the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Other items went to the Victoria and Albert Museum and the National Army Museum. The National Army Museum agreed to return a lock of Tewodros's hair in 2019. All the items taken from Magdala made European researchers more interested in Ethiopia's history and culture. This helped start modern studies of Ethiopia and research into the ancient Kingdom of Aksum.

Some of the looted treasures have been returned to Ethiopia over time. For example, a copy of the Kebra Nagast (an important Ethiopian book) and an icon of Christ were returned to Emperor Yohannes IV in the 1870s. In 1924, Empress Zawditu received one of Tewodros's two crowns, but the more valuable gold crown stayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum. In the 1960s, Queen Elizabeth II returned Tewodros's royal cap and seal to Emperor Haile Selassie during a visit to Ethiopia.

In 1999, people in Britain and Ethiopia created the Association For the Return of the Magdala Ethiopian Treasures (AFROMET). This group works to get all the treasures taken during the expedition returned to Ethiopia.

Images for kids