British Military Administration (Malaya) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

British Military Administration of Malaya

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945–1946 | |||||||||||||||

The Empire of Japan surrendered to the British Empire in Kuala Lumpur in 1945.

|

|||||||||||||||

| Status | Interim military governance | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Kuala Lumpur (de facto) | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Military administration | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Post-war | ||||||||||||||

| 2 September 1945 | |||||||||||||||

|

• British Military Administration established

|

12 September 1945 |

||||||||||||||

|

• Formation of Malayan Union

|

1 April 1946 |

||||||||||||||

| Currency | Malayan dollar British Pound | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

The British Military Administration (BMA) was a temporary government that took over British Malaya after World War II. It was in charge from August 1945 until the Malayan Union was formed in April 1946. The BMA was led by Lord Louis Mountbatten. Its main jobs were to help the area recover after the war and to set up a new government structure.

Contents

Why the BMA Was Needed

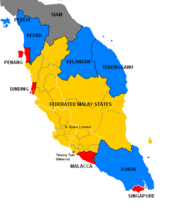

Before Japan took over, Malaya was split into different states and settlements. British officials wanted to bring these parts closer together. When Japan occupied Malaya, the British started planning how to free and govern the region. They decided on a two-step plan. First, a military government would bring back order. Then, a "Malay Union" would unite all the states under one government. This was to help Britain keep control of its territories in Malaya.

By early 1945, the British planned to liberate Malaya on September 9th. This plan was called Operation Zipper. However, Japan surrendered on August 15th, before the operation began. This meant the British had to quickly take back control of a huge area, including Malaya, Singapore, and other territories.

During the time between Japan's surrender and the arrival of British forces, there was some fighting. Different groups, especially Chinese and Malay communities, clashed. The Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) took action against people who had helped the Japanese. They also tried to raise money by force. Some Japanese soldiers were also attacked as they left certain areas.

Life Under Japanese Rule

During the early part of the Japanese occupation, Chinese people in Malaya were treated badly. This was because they had supported China in the war against Japan. The Japanese treated Indians and Malays better at first. They wanted Indians to help free India from British rule. They also did not see Malays as a threat. However, all three groups were later forced to help Japan's war efforts. This included giving money and working as forced labor. About 73,000 Malayans were forced to work on the Thai-Burma Railway. Around 25,000 of them died.

Japan took about 150,000 tons of rubber from Malaya. But this was much less than Malaya used to export. Since Malaya produced more rubber and tin than Japan could use, Malaya lost its income from exports. People's income dropped by about half by 1944.

Before the war, Malaya produced 40% of the world's rubber. It also produced a lot of the world's tin. But it had to import more than half of its rice, which was a main food. The Allied blockade meant that both imports and limited exports to Japan were greatly reduced.

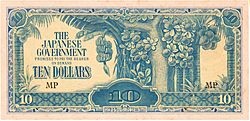

During the occupation, the Japanese replaced the Malayan dollar with their own money. Before the war, there was about $219 million Malayan dollars in use. Japanese officials thought they had put $7,000 to $8,000 million of their own money into circulation. Some Japanese army units even had mobile printing presses for money. No one kept track of how much was printed.

When Malaya was freed, there was $500 million of unspent Japanese money in Kuala Lumpur. Printing so much money in the last months of the war caused hyperinflation. This meant the Japanese money became almost worthless when the war ended.

The Allies dropped leaflets during the war. These leaflets said that Japanese money would be worthless after Japan surrendered. This idea was one reason why the money lost value as Japan faced more defeats. Even though prices were frozen in February 1942, by the end of the war, prices in Malaya were 11,000 times higher than at the start. Monthly inflation reached over 40% in August 1945. Fake money was also common. Both British and American secret services printed fake Japanese notes.

Because of Allied blockades against Japan, Malaya faced shortages of food and medicine by the end of the war.

British Return to Malaya

Penang was the first part of Malaya to be freed from Japanese rule. This happened on September 3, 1945. The Japanese soldiers in Penang officially surrendered on a British ship. The Royal Marines then took back Penang Island. The British later took over Singapore. The Japanese there officially surrendered on September 12. On the same day, the BMA started its work in Kuala Lumpur.

A surrender document for Malaya was signed in Kuala Lumpur. It was signed by Lieutenant-General Teizo Ishiguro, who commanded the Japanese 29th Army. Another surrender ceremony happened in Kuala Lumpur in February 1946. This was for General Itagaki, who commanded the Japanese 7th Area Army. The British also took back the four northern Malay states that Thailand had occupied in 1943. They slowly brought back the laws that were in place before the Japanese occupation.

How the BMA Was Set Up

The BMA was officially created on August 15, 1945. It was given full power over laws, justice, and administration in Malaya, including Singapore. Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten became the head of the BMA in September 1945. Lieutenant General Philip Christison was in charge of British forces in Malaya. Major-General Ralph Hone was the Chief Civil Affairs Officer for Malaya.

The BMA made several important announcements:

- Japanese courts were closed and replaced by military courts.

- Selling alcohol and food to soldiers was forbidden.

- The old Malayan currency became legal again. Japanese money became worthless.

- Rules were made to keep British and Allied forces safe. They also aimed to maintain public order.

- All land deals and financial institutions were temporarily stopped.

To make the administration smoother, Malaya was divided into 9 regions. Each region was controlled by a Senior Civil Affairs Officer. The main office for civil affairs was in Kuala Lumpur. Because it was a military government, the power of the Malay rulers (Sultans) was temporarily put on hold.

People Working for the BMA

Even though it was called the British Military Administration, many of its officials were civilians wearing military uniforms. However, the BMA often seemed not to care about what ordinary people needed. A big problem was that the BMA had few experienced administrators. Almost three-quarters of the senior staff had no past government experience. Only a quarter knew anything about Malaya.

Also, the military part of the BMA caused many complaints. One British observer noted that the army acted as if they were in a conquered enemy country.

Challenges for the BMA

When the BMA arrived, they faced many urgent problems. They had to:

- Arrest and disarm Japanese soldiers.

- Find and try war criminals.

- Release and send home prisoners of war.

- Fix important buildings and roads.

- Help key industries start up again.

- Disarm and send home guerrilla groups like the MPAJA.

- Bring back law and order.

- Distribute food and medical supplies.

Since the Japanese "banana money" was worthless, there was no legal money in circulation at first. Only a few people had kept their old pre-war money.

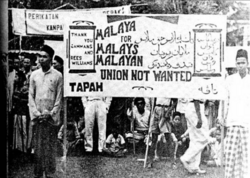

Before the war, British colonial governments were very strict about good behavior. There was almost no corruption. But under the Japanese, bribery, smuggling, and black market deals became common. These habits were hard to change when the British returned. The Japanese had also used the slogan "Malaya for the Malays." This made people want independence from colonial rule.

There were also big racial divisions. The Japanese had treated the Chinese badly at first. This was different from how they treated Malays and Indians. There were also attacks between Chinese and Malay communities. Malays felt that Chinese and Indian communities were taking advantage of them. There were also big differences in religion, culture, and language.

The military government was expected to make people feel safe. But they struggled with this. There was a lot of crime, including kidnappings and piracy. The high crime rate made people upset with the administration. The BMA did not do enough to stop crime and bring back order.

Because of its staff and economic policies, the BMA struggled to win the trust of the Malayan people. After the first few days, the British never truly regained public confidence. This failure led to other problems, like the rise of the Malayan Communist Party.

Economic Policies

The biggest challenge for the BMA was bringing back order to trade and jobs. This was after the Japanese left and the war ended. The destruction of buildings and roads was not only done by the Japanese. The British also used a "scorched earth" policy as they retreated in 1942.

It quickly became clear that the British government in London would not give money to rebuild Malaya. Malaya was lucky that Japan surrendered suddenly, which stopped more destruction. But the damage already done was huge. For example, it was estimated that $105 million would be needed to fix the railway system.

Also, a few days after the British arrived, they announced that Japanese money was worthless. This caused a huge shortage of money. People had no money to buy basic things like food and fuel. All the savings people had made during the war were gone overnight. This naturally made people more angry with the BMA.

The BMA also controlled how money was paid for imported goods. For example, goods from the US still had to be paid for in British pounds. Or they faced strict limits. This policy was not the BMA's choice. It came from the British government in London. This policy meant that only essential goods could be imported from outside the British currency area. This led to severe shortages of important supplies and machines. This slowed down Malaya's economic growth.

Finally, the British government in London set the selling prices for key goods. These goods included rubber, tin, and some timber. The prices were set very low and were not realistic. Most producers found them unacceptable. So, after the British returned, their economic plans upset business leaders in Malaya. Chinese businessmen, in particular, were very unhappy. People felt that British interests were put above Malaya's interests.

Steps Towards the Malayan Union

In May 1943, the British government started thinking about how Malaya should be governed after the war. They came up with a plan to combine the different Malay states and the Straits Settlements (but not Singapore). This new entity would be called the Malayan Union. The plan also suggested taking away political power from the Sultans. It also proposed giving citizenship to non-Malays who had lived in Malaya for at least 10 out of 15 years before February 15, 1942.

This plan was announced on October 10, 1945. Sir Harold MacMichael was given the job of signing new agreements with the Malay Sultans. This was to make the Union happen. MacMichael visited the Malay rulers, starting with Sultan Ibrahim of Johor in October 1945. The Sultan quickly agreed to MacMichael's plan. He really wanted to visit England that year. MacMichael visited other Malay rulers to get their agreement. Many rulers were very unwilling to sign the agreements. They feared losing their royal status and their states falling under Thai influence.

The full impact of the plan became clear on January 22, 1946. This was when the British government published its white paper on the Malayan Union. It also showed the effects of the agreements the Sultans had been persuaded to sign. The British government realized it had forgotten its own pre-war advice. This advice was about keeping the Malay population's special position.

Malay reaction was quick. Seven political activists organized a rally on February 1, 1946. They protested against the Sultan of Johore's decision to sign the agreements. Onn Jaafar, a district officer, was invited to attend the rally.

A Pan Malay Congress was held on March 1, 1946. This was the first of several meetings that led to the creation of UMNO. This organization aimed to oppose the Malayan Union. Onn also convinced the Sultans to boycott the opening ceremony for the Malayan Union. The British gave in. They agreed that while the Malayan Union would still start on April 1, 1946, talks would begin in July 1946 to replace it.

Images for kids

See also

- British Malaya

- British Military Administration (Borneo)

- Japanese occupation of British Borneo

- Japanese occupation of Malaya

- Singapore in the Straits Settlements

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |