British merchant seamen of World War II facts for kids

Quick facts for kids British Merchant Seamen of World War II |

|

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Branch | Merchant Navy |

| Role | Transportation of men and material |

| Part of | Ministry of War Transport |

| Colors | |

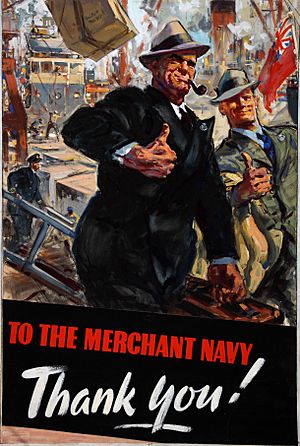

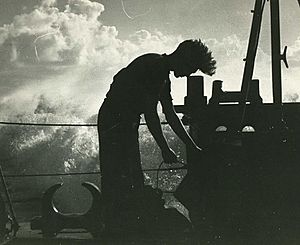

During World War II, brave merchant seamen sailed ships for the British Merchant Navy. Their job was to bring vital supplies to the United Kingdom. These supplies included raw materials, weapons, fuel, and food. Without them, the country could not have defended itself.

These seamen faced huge dangers. Many more of them were lost than in most other parts of the armed forces. They suffered greatly. Sailors ranged in age from just 14 years old to their late seventies.

About 144,000 merchant seamen were working on British ships when the war began. Up to 185,000 served during the war. Sadly, 36,749 seamen were lost due to enemy attacks. Another 5,720 were captured, and 4,707 were wounded. This means over 25% of all merchant seamen became casualties. One expert said that 27% of merchant seamen died because of enemy action.

Contents

- Who Were the Merchant Seamen?

- What Was the Merchant Navy?

- Merchant Seamen's Choices in Early War (1939-1941)

- Emergency Work Order of May 1941

- Merchant Seamen from Around the World (1939-1945)

- Women at Sea

- Naval Auxiliary Personnel

- Working on a Ship: Departments and Roles

- Working Hours and Pay

- Living Conditions and Food

- Career Progression

- Company Men

- Paperwork

- Nationalities of Seamen

- Gunnery Training

- Under Attack: Dangers at Sea

- Awards for Bravery

- Notable Merchant Seamen

- Images for kids

Who Were the Merchant Seamen?

Merchant seamen were ordinary people who chose to work at sea. Their way of working had not changed much for hundreds of years. They would "sign on" for a trip or several trips on a ship. After the journey, they were "paid off." Then they could choose to sign on for another trip or take a break.

These seamen were skilled professionals. They worked in many different roles. The youngest were "Boy" ratings, just learning the ropes. The most experienced were the Master Mariners, also known as captains. Everyone, no matter their job, was a merchant seaman.

A seaman might work on a huge 81,000-ton ocean liner like the RMS Queen Mary. This ship carried soldiers between Australia and England. Their next job might be on a small 400-ton ship. This smaller ship could carry coal along the coast of England. A trip could last a few weeks or more than a year.

Merchant seamen on British ships during World War II were both men and women. They came from Britain, India, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Some also came from the Fishing Fleet.

The youngest seamen were often "Boy" ratings. They worked as Deck Boys, Galley Boys, or Cabin Boys. They were usually 14 or 15 years old. For example, two brothers, Ken and Ray Lewis from Cardiff, were killed. They were 14 and 15 when their ship, the SS Fiscus, was sunk by a German U-boat.

Many families had several members sailing together. This led to great sadness when ships were sunk. Three members of the Attard family from Gozo, Malta died when the SS Newbury was lost. Three Roberts brothers also died when the SS Arakaka went down.

The oldest known merchant seaman was 79 years old. Chief Cook Santan Martins was killed in December 1940. His ship, SS Calabria, was sunk by a U-boat.

The British Merchant Navy in World War II was once called the "Merchant Service." It included all the commercial ships registered in Great Britain. These ships were run by British companies. They carried goods to and from the country and the Commonwealth. This effort was crucial for the war.

After the bravery of seamen in World War I, King George V gave them the name "Merchant Navy." In 1928, the Prince of Wales became "Master of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets." During World War II, the name Merchant Navy became common. From January 1940, merchant seamen wore a small silver badge. It had the letters "MN" on it.

The Ministry of War Transport (MoWT) was a British government department. It was created in May 1941. Its job was to control all transportation. This included both shipping and land transport. From then on, the MoWT decided every ship's route and cargo.

Merchant Seamen's Choices in Early War (1939-1941)

From September 1939, seamen could choose to sail and risk attack. Or, they could change jobs and work on land. They could also join the Armed Forces. However, the Royal Navy needed many men. They did not want merchant seamen to leave.

Once sailors signed a special agreement (T124x), the Royal Navy could move them to any ship. They could also give them Royal Navy training. Sailors did not know how dangerous their service would be at first. After signing, they had no choice but to keep serving.

In 1940 and 1941, ship losses were very high. 779 ships were sunk, and 16,654 seamen were killed or missing. This was about 49% of all British merchant sailors. Luckily for Britain, most seamen kept taking the risk. The nation's war supplies and food kept arriving.

Before May 1941, merchant seamen received no pay if their ship was sunk. This started from the moment the ship went down. Many survivors spent days or weeks in lifeboats. They hoped for rescue in brutal conditions. This time was seen as "non-working time," so they were not paid. The shipping company argued they no longer needed the seamen's services.

Emergency Work Order of May 1941

In May 1941, a new rule was passed. It was called "Emergency Work (Merchant Navy) Order, Notice No. M198." This rule was made because Britain was in a very difficult situation.

Under this new order, a Merchant Navy Reserve Pool was created. This pool made sure that available seamen were sent to ships that needed crews. It required seamen to keep serving for the whole war. They were guaranteed a wage for this time. This included time spent in lifeboats or as prisoners. They also earned two days of paid leave for each month they served.

Merchant Seamen from Around the World (1939-1945)

The British Merchant Navy was the biggest in the world. It needed more crew members than Great Britain had. So, many seamen from India, China, and West Africa joined. They crewed ships that often sailed to those areas. Also, men from Commonwealth countries served on British ships. Many others came from Scandinavia, the Netherlands, and other parts of the world. This even included some from Germany and Japan.

Life at sea was very open. There were few differences based on class, race, religion, age, or background. The mix of nationalities made it feel like a "Foreign Legion." Some sailors used different names. They did this to escape problems or start new lives.

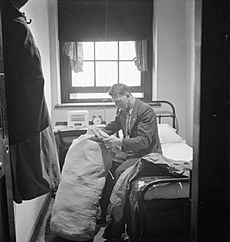

Many seamen came from British port towns. They followed their fathers and uncles to sea. Often, they sailed with family members. It was common for men not to have a fixed home. They would live in "Seamen's Hostels" in port for a week or two before their next trip.

Women at Sea

Traditionally, women worked on ocean liners and large passenger ships. They were usually chief stewardesses or assistant stewardesses. They also worked in laundries, as nurses, or in child care. Some worked in the shops on board. When passenger travel decreased, fewer women worked at sea. Nearly 50 women died when their ships were attacked and sunk during World War II.

One example was Lily Ann Green, a stewardess. She received an award for her bravery. This was when the SS Andalucia Star was sunk off West Africa in 1942. A small number of women also worked as radio officers. Maud Elizabeth Stean of the Canadian Merchant Navy died in 1944 at age 28. One or two women even sailed as "engineer officers." Victoria Drummond was a Second Engineer on the SS Bonita. She won awards for her bravery when her ship was bombed by the Luftwaffe.

In the early war years, Britain desperately needed fast ships to protect convoys. They did not have enough warships. So, several ocean liners were taken by the Royal Navy. They were turned into armed merchant cruisers (AMCs) by adding basic weapons.

These ships already had experienced crews. The merchant seamen were asked to sign an agreement (T.124). This meant they would serve alongside the Royal Navy in naval uniform. They would follow naval rules. About 10,000 seamen, mostly unwillingly, signed up for up to 12 months.

One AMC with many merchant seamen was HMS Jervis Bay. It fought a very brave but unequal battle. It faced the German cruiser Admiral Scheer. This was to protect Convoy HX 84. The Jervis Bay was lost, but it bought enough time for the convoy to escape.

Working on a Ship: Departments and Roles

Ships' crews were organized into different departments. These departments usually did not mix much. They lived and ate in separate parts of the ship. Only the master, mates, chief engineer, and radio officers ate and socialized together in the "Saloon."

The average age of a seaman on a British ship was about 36 in 1938. By 1945, it was about 32 years old.

During the war, many ships had old guns and small arms. Later, they got light 20mm cannons. These weapons were operated by trained merchant seamen. Sometimes, retired Royal Navy or Royal Marines gunners joined the crew. Later, members of the Royal Artillery Maritime Regiment also served. These ships were called DEMS (defensively equipped merchant ships). The number of gunners varied, from one or two to as many as 30.

The Ship's Master (Captain)

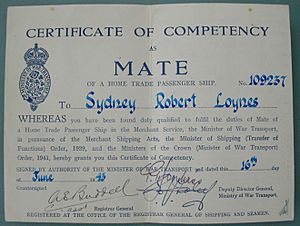

The master of a ship was also called the captain. They had a special certificate called a Master Mariner's certificate. Some even had an "Extra Master's" certificate for more navigation skills.

The shipping company hired the master. The master was in charge of everything: the ship, its cargo, the crew, and the success of the journey. Successful masters often stayed with a company for many years. They could become quite wealthy. When a company got new ships, a favored master might be given command of a new one.

It was common for a master to bring his wife to sea. This happened if the trip included ports she wanted to visit. At sea, the master's word was the final law. The first mate and boatswain made sure his orders were followed.

Deck Department

The First Mate (or Chief Officer on liners) had a lot of experience. They usually had a Master Mariner's certificate. They were gaining experience to become a master themselves. The First Mate was in charge of the cargo. They made sure it was loaded and unloaded correctly. They also supervised the younger mates in navigating and running the ship.

The Second Mate reported to the First Mate. They usually had a First Mate certificate. The Third Mate reported to the senior mates. They usually had a Second Mate's certificate and were studying for their First Mate's ticket. Larger ships might have a fourth or fifth mate. The biggest ocean liners could have up to a 10th mate.

The ship's carpenter and boatswain (bosun) were senior deck crew. They were usually very experienced and strong personalities. The boatswain's mates were also trusted seamen. They helped keep the deck crew in line.

Able Seamen were experienced sailors. The highest-ranking were "quarter masters." They steered the ship. "Ordinary seamen" had less experience. The lowest were "deck boys," typically 14 or 15 years old, learning to be seamen.

Ships often carried apprentices. These young people signed up with a shipping company for four years. They learned to be seamen, hoping to become mates. Unlike Royal Navy midshipmen, apprentices worked and lived with the Able Seamen. Some ships had a storekeeper. This was an experienced older Able Seaman who managed the ship's supplies.

Engineering Department

The Chief Engineer had to have a First Class Certificate in Steam. They had a lot of sea experience. They were responsible for all the ship's engines and machinery.

The Second Engineer reported to the Chief Engineer. They always had a First Class Certificate in Steam. They were gaining experience to become a chief engineer. There were also third engineers, fourth engineers, and so on. The number depended on the ship's size. They usually had trained in heavy engineering on land. Then they went to sea and got a Second Class Certificate in Steam.

The senior engine room crew were the donkeyman and the greaser. The donkeyman was in charge of the ship's extra power and cargo cranes. The greaser made sure all engine parts were oiled correctly. They also kept the Firemen and Trimmers in order.

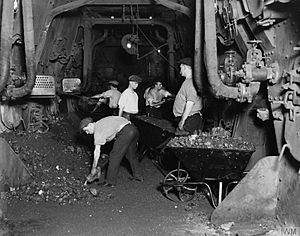

The "black gang" were the men who handled the coal. They spent their working lives covered in coal dust. Most ships used coal for power. They were split into Firemen and Trimmers. Firemen fed tons of coal into the furnaces to keep the steam going. Trimmers worked in the ship's coal bunkers. They loaded coal into wheelbarrows and took it to the Firemen. They also kept the coal level in the bunkers even to keep the ship stable.

Catering Department

The bigger the ship, the larger the catering department. On a general cargo ship, the Chief Steward managed all food, cleaning of officer cabins, and supplies. He usually had two or three Assistant Stewards. A Chief Cook also reported to him, with assistants and a Galley Boy. One assistant was usually a baker. On long trips, food was very important. A cook who made bad food quickly became unpopular.

Working Hours and Pay

Merchant seamen's pay was low compared to factory or construction workers on land. A big reason was their long hours. A seaman's basic work week was 64 hours before overtime. Factory workers often worked 44 or 47 hours. In 1943, the seaman's basic week was cut to 56 hours. Seamen felt upset when they learned that U.S. Merchant Marine sailors earned more than double their wages.

Living Conditions and Food

Food was often plain and not very good. Ships usually did not have good refrigeration for crew food. Any frozen food came from an ice-box. After the ice melted, salt meat from barrels and butter from tins were common. Fresh eggs, fruit, and vegetables might be bought in port. This depended on the Chief Steward's budget and the Captain's permission. The Captain wanted to make sure the trip was profitable.

Seamen lived in dark, small, damp, and often rusty dorms. They had wooden bunks, three or more high. There was no running water or heating. Each man might get one or two blankets. They were expected to bring their own "donkey's breakfast." This was a sack filled with straw to use as a mattress.

Before the war, seamen tried to join ships known for "good feeding." These ships had better food. Others were avoided for poor food. One company, Hogarth & Sons, was even called "Hungry Hogarth's" by seamen.

Career Progression

Any Able Seaman could move up in their career. This depended on their experience, skills, and hard work. They could take exams to become a Second Mate, then a First Mate, and finally a Master Mariner. It was not unusual for a former Deck Boy to become a captain.

To get a Second Mate's certificate, a seaman needed several years of sea experience. This could be as an Apprentice (Cadet) or an Able Seaman. No matter their background, they lived and worked with other seamen.

There was little class difference at sea. This was especially true on general cargo ships. However, large ocean liners had more strict rules and uniforms. This sometimes attracted officers who preferred that kind of environment.

Company Men

Many certified officers, both deck and engineering, stayed with specific shipping companies. They only sailed on ships owned by that company. They could often get promoted if a master who trusted them got his own command.

Sometimes, senior crew like Carpenters, Boatswains, Quarter Masters, Donkeymen, and Chief Stewards also preferred this path. Like their officers, they might stay on a favorite ship for ten years or more.

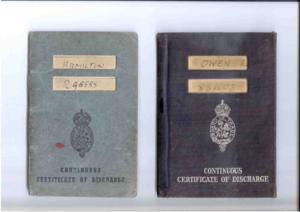

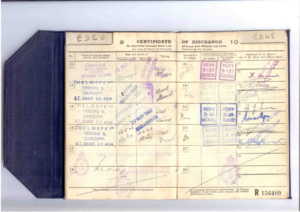

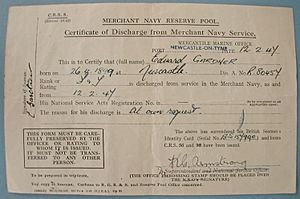

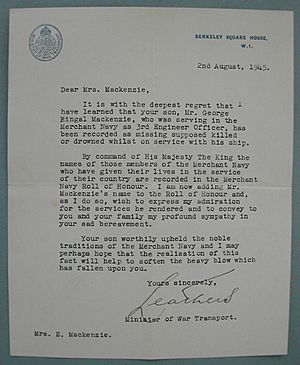

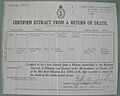

Paperwork

When a seaman finished a trip, they received their pay. They also got a detailed payslip. This showed their basic and overtime hours, and any money paid during the trip. They also got a Discharge Slip. This slip listed the ship's name, their job (like Able Seaman), and the dates they served. It also showed how well they worked and behaved.

If the seaman had a Discharge Book, these details were written in it. This book was a record of their whole career at sea. Seamen hoped for a "VG/VG" rating. This meant "very good" for both work and conduct. Lower ratings like "G" (Good) or "Sat" (Satisfactory) could affect their chances of getting a good job on a good ship next time.

At the end of the war, a seaman could not leave the Merchant Navy without approval. The only exception was if they were too sick to sail. Many seamen continued to sail because it was their usual job.

Nationalities of Seamen

Most seamen on British Merchant Navy ships were British. However, a 1938 study found that 27% were from India or China. Another 5% were Arabs, Indians, Chinese, West Africans, or West Indians living in UK ports.

A typical British cargo ship crew in May 1940 showed this mix. The deck officers were from Scotland, Wales, and England. The engineer officers were from England and the Netherlands. The engine room crew were mainly Somali Arabs. The deck crew included Indians, one man from Burma, one from Fiji, a West Indian, a Chinese, and a Liverpudlian. The chief steward was from Cardiff. The cook and two galley boys were from Liverpool. The oldest crew member was the 55-year-old cook. The youngest was the 15-year-old galley boy.

Records show that men from all British Commonwealth countries served. Many from Scandinavian, Baltic, and European countries also served. Before the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Japanese seamen were among the crews. Several were killed in U-boat attacks alongside British sailors. Others, like Kenji Takaki, were captured and held with British seamen.

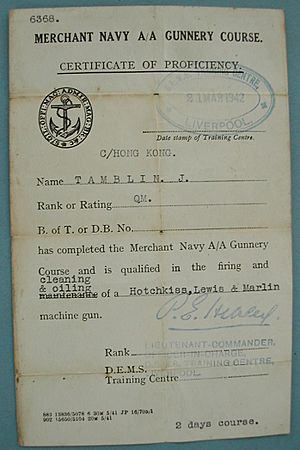

Gunnery Training

Merchant ships quickly got defensive weapons. These included old World War I guns and machine guns. Crews were trained to use them. Gunnery courses were held regularly in major ports. Naval and Royal Marine instructors taught the seamen. Certificates were given to those who finished the training. This allowed them to fight back if attacked.

Under Attack: Dangers at Sea

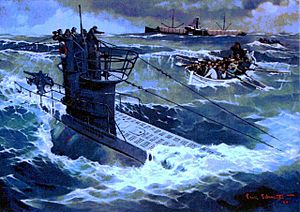

Merchant seamen started dying within nine hours of the war beginning. On September 3, 1939, a U-boat torpedoed the passenger ship SS Athenia. It then attacked the sinking ship with gunfire, destroying her radio room. The ship sank, and 118 people died. This included 19 crew members, 5 women, a 15-year-old Bell Boy, and a 65-year-old Watchman.

Seamen continued to serve all over the world. Some returned to sea even after their ships were sunk multiple times. The author John Slader survived three sinkings. This was not unusual for seamen.

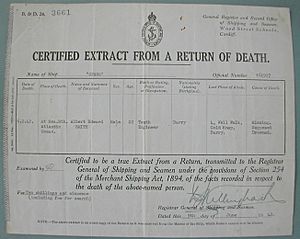

Killed or Missing

When a merchant ship was torpedoed, it behaved differently depending on its cargo. A tanker with aviation fuel might explode and spread burning fuel. A ship loaded with timber might stay afloat for days. A ship with iron ore would usually sink in less than a minute.

Sometimes, there was time to launch lifeboats. Other times, seamen struggled to survive in the water. They tried to hold onto any floating debris.

It is hard to know the exact number of merchant seamen lost in World War II. The government did not automatically honor them like the armed forces. Only deaths proven to be from enemy action were recorded. 36,749 members of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleet are remembered.

In March 1946, a report stated 34,018 deaths on British ships or abroad. 27,790 died from enemy action. 6,228 died from other causes. These included ships that disappeared or were lost to friendly mines or storms. Later figures varied, but the total of 36,749 dead is widely accepted.

The deaths of 2,713 Naval and DEMS gunners and 1,222 Royal Artillery gunners are counted separately. Many South Africans and New Zealanders also died. They are likely included in the British Merchant Navy total. Potentially, over 6,000 more merchant seamen died but are not officially commemorated.

Time Adrift at Sea

After a ship sank, merchant seamen hoped to get into lifeboats or onto rafts. They would wait for rescue, living on biscuits and water. Many wounded or tired survivors did not make it. They died in the sea, which could be covered in thick, burning oil. Survivors in Arctic waters faced even harsher conditions.

Lifeboats were often overturned in rough seas. They had to be righted before survivors could get in. Some had sails, others just drifted. Some survivors were rescued in hours. Others drifted for weeks. Some boats full of survivors were never seen again.

Some convoys had "Rescue Ships." These ships sailed with the convoy. Their job was to stop and save merchant seamen from the water.

Lifeboats that were not rescued sometimes traveled long distances. One lifeboat from SS Britannia sailed 1,500 miles to land. During 23 days adrift, 44 survivors died from wounds and exposure. Two survivors from the SS Anglo Saxon survived 70 days in an open boat. Merchant seaman Poon Lim survived 133 days adrift. The record was 135 days, held by two Indian seamen, Mohamed Aftab and Thakur Miah.

German U-boats and Italian submarines that sank ships often helped survivors. Submariners would right overturned lifeboats. They provided food and drink. They often gave directions to land. Some U-boat commanders were known for their humanitarian acts.

However, help to survivors changed after a US plane attacked a U-boat. This U-boat was helping survivors of the liner Laconia. It had broadcast for help and was flying Red Cross flags. After this, assistance from submarines became much less common.

Prisoners of War

Very few merchant seamen were taken prisoner on German or Italian submarines. There was limited space. Sometimes, a ship's master or officer might be taken. They would be sent to a prisoner of war camp when the U-boat returned to base. Several captured merchant seamen died as prisoners on U-boats when they were sunk by Allied forces.

Most merchant seamen taken prisoner were captured by German "Raiders." These were heavily armed merchant ships disguised as neutral vessels. They would capture Allied ships and their cargo. The captured seamen might be held on prison ships. Or, their ships might be sailed to a German port by a German crew.

After several ships were captured, 327 merchant seamen were held on the SS. Portland. They were being taken to Germany. Led by Able Seaman Alfred Fry, a merchant seaman, they tried to set the ship on fire and take it over. The attempt failed after a gun battle. The Germans kept control. The seamen were charged with "Mutiny." Many got long prison sentences. Fry was sentenced to death, but he survived, though badly beaten.

About 4,900 merchant seamen captured by the Germans were held at a camp called MILAG. This was inside Sandbostel Internment Camp near Bremen, Germany. One prisoner, First Radio Officer Walter Skett, was shot and killed by a German guard while trying to escape.

Like military prisoners, merchant seamen tried to escape. At least one, Arthur H (Dick) Bird, got home from Germany through Sweden. Others broke out from camps or during transport.

In the Far East, merchant seamen held by the Japanese faced very harsh conditions. Many died from disease or starvation.

Awards for Bravery

Merchant seamen, including women, who showed great bravery could sometimes get military awards. But this only happened if they worked with the Royal Navy. This included major landings (like North Africa, Sicily, and D-Day) or vital convoys (like the Arctic Convoys or the Malta Convoy).

Other times, seamen received civil awards. These were often given for diligent work or charity. People in Parliament felt that merchant seamen were not getting enough recognition. They tried, but failed, to create a special "Merchant Navy Cross for Gallantry."

In one special case, Captain Dudley Mason of SS Ohio received a George Cross. This award is for great bravery "not in the face of the enemy." Captain Mason's ship was carrying vital fuel to Malta during a siege. His tanker was burning after being torpedoed and bombed. A German plane even crashed on its deck. He brought the ship to Malta despite all this. He could not get the Victoria Cross because he was a civilian.

| Award | Number |

|---|---|

| George Cross | 5 |

| Empire Gallantry Medal | 1 |

| Albert Medal | 11 |

| Knighthood | 10 |

| CBE | 50 |

| Distinguished Service Order | 18 |

| OBE | 1,077 |

| Distinguished Service Cross | 213 |

| George Medal | 49 |

| MBE | 1,291 |

| Distinguished Service Medal | 421 |

| Sea Gallantry Medal | 24 |

| British Empire Medal | 1,717 |

| Mention in Despatches | 994 |

| King's Commendation | 2,568 |

| TOTAL | 8,449 |

This table shows a summary of awards given to merchant seamen.

- CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire): Given to senior masters of large ships. For example, Selwyn Capon, Master of the MV Empire Star. He sailed his ship from Singapore under air attack, loaded with refugees, and brought them to safety.

- OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire): Sometimes given for bravery by masters, chief engineers, or senior mates. Also for serving on many voyages with attacks from bombers, U-boats, or mines. Or for helping survivors in lifeboats, or for service as prisoners of war.

- MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire): Awarded for similar brave acts as the OBE, but to more junior mates, engineers, and radio officers. First Radio Officer Arthur H. Bird escaped from a German prison camp and got home. He received an MBE.

- BEM (British Empire Medal): Almost all BEMs were given to seamen for great bravery in fighting fires on ships. Also for manning machine guns against attacks, helping trapped shipmates, or bravery in lifeboats.

- Commendations (King's Commendation for Brave Conduct (1916–1952)): Many merchant seamen received this award for their bravery in action. For example, John Morrison Ruthven, Chief Refrigeration Engineer, was given a Commendation after his death. He stayed on his torpedoed ship trying to rescue trapped seamen.

Some seamen received multiple Commendations. Captain E.G.B. Martin, for example, had his ships sunk three times. He received the award three times, including one after his death.

To better recognize the bravery of merchant seamen, Lloyd's of London created their own award. It was called the Lloyds War Medal for Bravery. It became a very respected award.

Notable Merchant Seamen

- Chick Henderson – a singer

- Thomas Wilkinson – received the Victoria Cross

- Dudley Mason – received the George Cross

- Kevin McClory – an Irish movie director

- Lucian Freud – a famous artist and painter

- Thomas Kelly – received the George Cross

- Richard Been Stannard – received the Victoria Cross

- Frederick Treves – an actor

- Freddie Lennon – father of John Lennon

- James Redmond – a BBC broadcaster

- Dudley Pope – an author

- Markey Robinson – a boxer and artist

- Kenji Takaki – a Japanese prisoner in Germany, later a movie actor

- Mark Arnold-Forster – a journalist and author

- Frank Laskier – a merchant seaman and author

Images for kids

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |