Burning of Winchester Medical College facts for kids

The Winchester Medical College (WMC) building was located at 302 W. Boscawen Street in Winchester, Virginia. On May 16, 1862, Union soldiers burned the college. All its records, equipment, museum, and library were destroyed. The College never opened again after this event.

Contents

Winchester During the Civil War

Winchester was known as a strong supporter of the Southern cause during the Civil War. This meant many people there also supported slavery. While some people in Winchester were against slavery and supported the Union, they usually kept quiet. Most visible leaders, like politicians and doctors, were pro-slavery. The Piedmont region of Virginia, which includes Frederick County, had the strongest feelings for the South in the state. Union soldiers saw Winchester as a "hot bed of treason."

Winchester stood for everything the North was fighting against. It openly defended and even celebrated slavery. Union troops often came into contact with cities in northern Virginia. Of these, Winchester was seen as a hostile enemy.

Senator James M. Mason

One of the most important men in Winchester before the war was James M. Mason (1798–1871). He was a Virginia Senator for three terms. Mason owned a large estate called Selma, which overlooked the city. He spent his career fighting against change.

Mason was removed from Congress in March 1861 because he supported the Confederacy. He strongly believed in slavery. He even wrote the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This law was very unpopular and often ignored in the North. Mason also led the Senate committee that investigated John Brown's raid.

Later, Mason became the Confederacy's main diplomat. In 1861, the Confederacy sent him to Europe. He tried to get England or France to recognize the Confederacy or offer financial help. This effort was not successful.

Mason was closely linked to the "old South." He believed that Black people were a "great curse" to the country. He thought giving Black people the right to vote would lead to chaos. Mason also did not think it was wise to educate Black people, whether they were enslaved or free. He believed freeing slaves would make them "barbaric." He even thought enslaved Black people were better off than free ones. Mason had a kind relationship with his own enslaved people. But he wrongly assumed that all slave owners were kind.

Union troops first used Mason's estate, Selma, for their offices. At first, some officers might not have known who Mason was. But they soon learned. A Union chaplain gave a sermon in front of the courthouse. He called Senator Mason a "traitor" and said he had pushed Virginia into the rebellion.

General Nathaniel P. Banks led the Union troops. He was a former Speaker of the House of Representatives and Governor of Massachusetts. Banks knew exactly who Mason was and what he stood for.

Once the Union soldiers understood how much Northerners hated Mason, they began to destroy his house. They used pick-axes to remove the roof. Later, the walls were pulled down. Anything that could burn was chopped up for firewood. They destroyed the house so completely that "not one stone remains upon another." Even the enslaved people's houses, other buildings, and fences were gone. Some trees were also damaged. Stone from the house was used to build a nearby fort called Star Fort. Mason later said his home was "destroyed, or rather obliterated." He never lived in Winchester again.

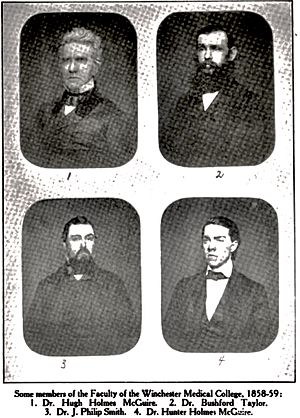

Hugh and Hunter McGuire, Doctors

Dr. Hugh Holmes McGuire (1801–1875) was another important man in Winchester. He founded the Winchester Medical College. He was a very respected doctor in northern Virginia. Even though he was 60, Dr. McGuire strongly supported the Southern cause. He became a surgeon in the Confederate Army. He was in charge of hospitals in Greenwood and Lexington.

His son, Hunter Holmes McGuire (1835–1900), was even more dedicated to the South. He studied medicine in Philadelphia. When John Brown was executed, Hunter McGuire was very upset. He helped organize about 300 medical students to leave Philadelphia. They traveled by a special train to Richmond, Virginia. The Medical College of Virginia paid for their trip. They were greeted with great excitement in Richmond.

When the war started, Hunter McGuire became a medical director for the Confederate Army. He was also the personal doctor for famous Confederate Generals Stonewall Jackson and Jubal Early. After the war, in the 1890s, he led a group that reviewed history textbooks. They wanted to make sure the Southern viewpoint was fully and correctly shown. In 1907, he published a book that supported the "Lost Cause" ideas. These ideas claimed that slavery was not the cause of the war and that the North started the fighting.

Richard Parker

Richard Parker was the judge who sentenced John Brown to death. He lived in Winchester.

Stonewall Confederate Cemetery

The Stonewall Confederate Cemetery has monuments from every Confederate state. It also has monuments for Kentucky and Maryland, and for unknown Confederate soldiers. At a dedication ceremony in 1879, Winchester invited Senator John Tyler Morgan from Alabama. He complained that the Union planned to end slavery, which he said went against the Constitution.

There are many Confederate cemeteries in the South. But most are local. The Stonewall Confederate Cemetery is special because it has a stone marker for each Confederate state, with soldiers from those states buried there. Only two other cemeteries like it exist outside of Virginia.

The Winchester Medical College

The Winchester Medical College was an important medical school. It was the first medical school in Virginia. The Medical College of the Valley of Virginia was first started in 1825. It operated from 1826 to 1829. Its exact location is not known, but it was likely in a small office behind Dr. Hugh Holmes McGuire's home. The college closed when a senior doctor left.

About 20 years later, Dr. McGuire restarted the medical school as the Winchester Medical College in 1847. The state loaned it $5,000. The college built a red brick building near the homes of Mason and McGuire. It had a special room for operations with a large dome for light. It also had two lecture halls, a room for dissections, a chemistry lab, a museum, a library, and offices.

The college graduated 72 students before it closed in 1861. This was when Virginia left the Union and joined the Confederacy at the start of the Civil War. All the students joined the army. Hugh's son, Hunter Holmes McGuire, began his medical studies there.

Like other medical schools in the South, most of the bodies used for dissection were Black. Because of this, Black people in Winchester feared and disliked the College. Some students even bragged about digging up graves of Black people at night.

A Cemetery Discovered

In 1928, a barn was torn down on a farm near Winchester. During digging for a new house, a cemetery was found under the barn. It did not contain full bodies or skeletons. Instead, there were loose human bones, enough to put together several skeletons. People generally believed these bones were from bodies dissected by students of the old Winchester Medical College many years ago. There was no way to identify the bones. The college's records were burned with the building, so it is unknown what happened to the bones after they were found.

What Union Soldiers Found

On March 11, 1862, Confederate troops left Winchester. Union soldiers, led by General Nathaniel P. Banks, entered the city the next day. They found the Winchester Medical College empty. No classes had been held for a year. In the summer of 1861, it had been used as a hospital.

Union troops found two things in the medical college that shocked and angered them.

Burning the College

Union soldiers under General Banks burned the Winchester Medical College on May 16, 1862. This happened just before they retreated as Stonewall Jackson's army approached the city. Soldiers stopped fire trucks from putting out the fire.

A former student wrote about the burning:

Winchester, Va., Sept. 7, 1894.

James Monroe,

Dear Sir: — The postmaster asked me, as the oldest living graduate of the old Winchester Medical College, to answer your note. The college was burnt by General Banks' army in May, 1862. He himself regretted it, but his New England doctors and chaplains did it—applied the torch with their own hands. They proclaimed that theirs was a campaign of education. ...Only one of the professors now lives—Dr. Hunter McGuire, of Richmond.I am, sir, respectfully yours, D. B. Conrad.

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |