Calhoun Colored School facts for kids

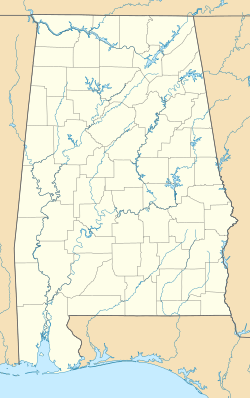

The Calhoun Colored School was a special private school in Calhoun, Lowndes County, Alabama. It was a boarding school, meaning some students lived there, and a day school for others. The school was founded in 1892 by Charlotte Thorn and Mabel Dillingham. They were teachers from New England.

They started the school with help from Booker T. Washington of Tuskegee Institute. The goal was to educate Black students in rural areas. At that time, Alabama had segregated schools, meaning Black and white students went to separate schools.

The Calhoun Colored School first taught students using an "industrial school" model. This meant they learned practical skills for jobs. The school also did amazing things for the community. It helped 85 families buy their own land. This was very important for their future.

The school also worked with the county to improve a local road. This helped farmers get their products to market easily. Over time, the school improved its teaching. It built a large library and offered more academic subjects.

Contents

Why is the Calhoun School Important?

The principal's house is the only original building left from the Calhoun Colored School. It is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This shows how important the school was for educating African Americans.

What is the Calhoun School Site Like Today?

In 1943, the state of Alabama took over the Calhoun Colored School. A new school building was built on the same land. Today, this site is home to a public high school. It is run by the Lowndes County Board of Education. Most people in Lowndes County are African American.

The principal's house on County Route 53 is the last building from the first school. It is recognized for the school's important role. It helped educate African Americans in Lowndes County.

How Did the Calhoun Colored School Start?

In 1891, the United States was still recovering from the American Civil War. Many African Americans in the rural South worked as sharecroppers. This meant they farmed land they didn't own and shared crops with the landowner.

The South relied on cotton, but its price kept falling. This made it hard for people to make money. In Calhoun, Alabama, most people were African American. But white leaders controlled politics and society.

State laws made it hard for African Americans to vote. In 1901, a new state constitution created even more barriers. This stopped most Black people and many poor white people from voting.

Lowndes County was part of the "Black Belt," an area with rich soil for cotton. Before the Civil War, it had many large cotton farms. In 1890, Lowndes County had the highest number of Black people compared to white people in Alabama. Most Black people worked as sharecroppers.

Booker T. Washington, who led Tuskegee Institute, asked teachers to help educate Black people in Alabama. He spoke about the people of Calhoun and their strong desire for education. Two teachers from Hampton Institute, Charlotte Thorn and Mabel Dillingham, answered his call. They were white women from New England. They traveled with Washington to Calhoun to start the school.

Thorn and Dillingham used their connections to raise money. They also asked for donations of all kinds. They wrote articles about the school in The Southern Workman magazine. This helped them get more support.

The Hampton-Tuskegee Education Model

| Calhoun Colored School | |

|---|---|

| Location | |

|

Lowndes

,

Alabama

|

|

| Information | |

| Type | Private, boarding, segregated |

| Founded | 1892 |

| Founder | Charlotte Thorn and Mabel Dillingham |

| Closed | 1945 |

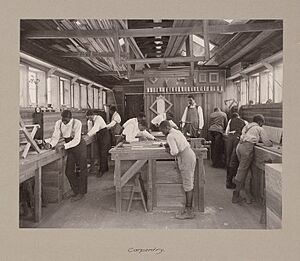

Carpentry class at the Calhoun School |

|

Booker T. Washington, Charlotte Thorn, and Mabel Dillingham based the Calhoun Colored School on the Hampton-Tuskegee model. This model had two main parts.

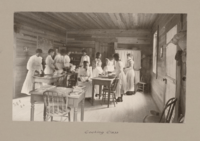

First, students would get a basic elementary education. Then, they would learn industrial skills in high school. This prepared them for jobs in rural areas. Boys learned farming and trades. Girls learned homemaking, sewing, and laundry skills. The best students were encouraged to become teachers. They would then help others learn in their communities. There was a big focus on improving reading and writing for everyone.

Second, the school was not involved in politics. The education was not meant to challenge the way society was organized. It helped African Americans support themselves within the existing system. Washington believed that if a Black school challenged politics, white citizens might close it down. This type of education was different from the "classical" education many white students in the North received.

Some highly educated African Americans, like W. E. B. Du Bois, disagreed with this model. He thought it was too limited. He believed that the most talented students should get a full academic education. This would help the entire Black community move forward.

In October 1892, Thorn and Dillingham met with 300 local Black people. They wanted to learn about the new school. Many adults helped build the school buildings. By 1896, the school had a working farm of 100 acres. It had 300 students, with 40 living at the school. There were also 13 teachers.

The Hampton-Tuskegee model focused on teaching basic skills. Some critics felt it limited the dreams of Black people in the South. But it also fit the needs of Alabama's farming economy. It didn't push for big social changes. Most white citizens and some Black people would not have supported such ideas then.

Helping the Community: Land and Roads

Mabel Dillingham died in 1895. Her brother, Pitt Dillingham, worked with Charlotte Thorn for several years. He helped raise money by giving speeches in the North.

The school's founders had ideas beyond the Hampton-Tuskegee model. They knew that owning land was key for Black people to be independent. So, in 1894, the school started a land company. They had over 4,000 acres of land. They sold land in 40- to 60-acre plots. Friends of the school in the North helped with financing.

In the first 13 years, 85 people bought land. They built real houses with three to eight rooms. These were much better than the sharecroppers' cabins they lived in before.

Calhoun was near a railway, but shipping costs were too high for small farmers. The dirt roads were also very bad, especially when it rained. The school worked to improve the roads. This would help farmers get their goods to market.

It took almost 40 years. But Charlotte Thorn's nephew, Thorn Dickinson, helped make it happen. He used his engineering skills to plan the road. School students helped grade the road. The county then covered it with gravel. This became Lowndes County Route 33.

Learning to Read and Write

At first, the school's reading program included reading aloud and memorizing poems. Students learned to appreciate literature. They also connected school learning to home and community. Teachers brought in outside materials to interest students. They discussed words, helped with speaking clearly, and taught students to write their thoughts.

Later, the school offered night classes for adults. These classes were part of the Hampton-Tuskegee model. Teachers and students visited homes to teach people to read and write. They also held mothers' meetings, church services, and holiday celebrations on campus.

Donations of money and books, mostly from Northern supporters, helped create the school library. The school leaders followed the Hampton-Tuskegee model. But their teaching methods for reading and writing were much richer.

The Calhoun Colored School started by strictly following the Hampton-Tuskegee model. But over time, it developed a more "classical" education. This meant focusing on thinking and problem-solving. It included a wide-ranging reading and writing program.

When the school hired college-trained teachers, they used new teaching methods. These methods were like those in better schools in the North. However, students did not make as much progress as hoped. Even though they were poor, they wanted to learn and had family support. Some people think the social attitudes of that time limited what teachers expected from African American students.

Leaders of the Academic Department

From 1892 to 1945, six different people led the Academic Department. Each leader made improvements to the school's curriculum.

Susan Showers (1896) started reading clubs for students. Teachers visited homes. She also organized community events and religious services. Working with the community was not part of the Hampton-Tuskegee model.

Clara Hart (1898) took over from Susan Showers. She started the first free kindergarten at the school. She made sure reading was taught in every grade. She also focused on good literature and writing.

Mabel Edna Brown (1907) was the first African American to lead the Academic Department. She wanted to offer a more classical education. This was a big change from the Hampton-Tuskegee model. She said they were trying to improve thinking and expression. She doubled the time spent on reading and writing in the younger grades. By 1909, the kindergarten used games to teach reading, writing, and math. The school also started asking for books by African American authors for the library.

Jessie Guernsey joined Calhoun in 1912. She had degrees from New York City's Columbia Teachers College. Under her, students used interesting books to learn reading. She also brought back creative writing for spelling and grammar. She continued literary clubs, debates, and music training. The elementary grades used state-approved textbooks. Older students used more literature, newspapers, and magazines. The school added a tenth grade. The growth in classes and community work put a strain on money. Also, county schools for African American children were becoming more popular. Many Calhoun graduates became teachers in these county schools.

In the mid-1920s, Edward Allen became the first man to lead the Academic Department. He changed the focus from basic reading to higher-level thinking skills. This was another big step away from the Hampton-Tuskegee model. During his time, he greatly expanded the library.

In the late 1920s, R. Luella Jones came to the school. She made the classes more challenging. This helped the school get official recognition. It also helped graduates get into colleges. She added college prep classes like Latin, more science, and math. Industrial arts became an optional class. She also added eleventh and twelfth grades so students could graduate from Calhoun. The library grew to over 6,000 books.

The School's Final Years

Charlotte Thorn passed away on August 29, 1932. She had led the school for more than 30 years. The school continued as a private school for a few more years. But the Great Depression made it hard to find money. Also, new machines in farming meant fewer jobs in rural areas. Many Black people moved North for jobs. This reduced the local population. The school could no longer afford to stay open.

Documentary About the Calhoun Colored School

In 1940, the Harmon Foundation made a film about the school. It was called "Calhoun School, The Way to a Better Future (1940)."

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |