Cape Field at Fort Glenn facts for kids

|

Cape Field at Fort Glenn

|

|

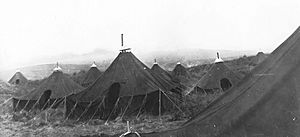

Fort Glenn Airfield in 1942

|

|

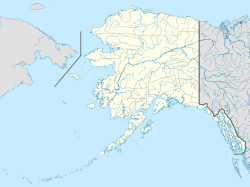

| Location | Umnak Island, Alaska |

|---|---|

| Area | 7,550 acres (3,060 ha) |

| Built | 1942 |

| Architect | U.S. Army |

| NRHP reference No. | 87001301 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | May 28, 1987 |

| Designated NHLD | May 28, 1987 |

Cape Field at Fort Glenn was an important military base during World War II. It included Fort Glenn, which was an airfield for the United States Army Air Corps (later called Cape Air Force Base), and the nearby Naval Air Facility Otter Point. Both were located on Umnak Island in the Aleutian Islands of southwestern Alaska. This site was recognized as a special historical place in 1987, being added to the National Register of Historic Places and named a National Historic Landmark.

History of Fort Glenn

Building the Base

After the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, leaders in the United States Army Air Forces realized Alaska needed better protection. They decided to send more modern planes and soldiers there. However, the Alaskan Air Force didn't have enough airfields to hold all these new planes and units.

So, plans were made to build new air bases, especially in the Aleutian Islands to defend Dutch Harbor. Construction on Umnak Island and Cold Bay began secretly in January 1942. Workers pretended they were building a fish cannery to keep the project hidden. The first U.S. Army engineers arrived at what would become Fort Glenn Army Air Base on January 17, and construction started quickly. A Navy airfield, Otter Point Naval Air Facility, was built right next to the Army base.

The original plan was for three hard-surface runways, but four were eventually built. Time was very important because the defense of Dutch Harbor depended on these airfields. Instead of waiting for concrete, engineers used a new material called Pierced Steel Planking (PSP). This was like giant metal mats that could be quickly laid over packed gravel. This made the airfield usable in all kinds of weather. About 80,000 pieces of this matting had to be brought to the island by ship.

Construction crews worked 24 hours a day in three shifts. They laid down runways and built basic support buildings, water and sewer systems, electricity, communication lines, and places to store fuel and ammunition. All these things were needed to turn a remote island into a working airfield for large bombers. A 5,000-foot PSP runway was finished by April 5, 1942. The first plane, a C-53, landed on March 31. The main runway officially opened on May 23. At that time, Fort Glenn's first runway was the westernmost U.S. Army airfield in the Aleutian Islands.

The first fighting unit, the 11th Fighter Squadron, arrived at Fort Glenn on May 26 with their P-40 Warhawk fighter planes. More construction continued through 1942. Four runways, each 5,000 feet long and 175 feet wide, were completed. All runways had four layers of asphalt over the PSP. Two extra emergency landing fields were also built nearby.

Hundreds of Quonset hut buildings were constructed to replace the temporary tents. These huts protected the workers from the sudden, strong storms common on the island. The base had housing and dining areas for many officers and soldiers, plus recreational buildings. There were also storage facilities, a large hangar for aircraft, and offices. Radio and radar stations were built for communication and tracking. Even a small hospital with 8 beds was available.

Fighting in the Aleutians

On June 3, 1942, the Imperial Japanese Navy launched surprise air attacks on the U.S. Army barracks and Navy base at Dutch Harbor. This attack marked the start of the Aleutian Islands Campaign. In response, the P-40 fighters from Fort Glenn AAB, along with Navy planes, fought back against the Japanese aircraft. Other U.S. planes from Elmendorf Field also joined the battle.

During the fighting, the U.S. lost several planes, including bombers and fighters. The Japanese lost several of their own planes, including "Zero" fighters and "Val" dive bombers. On June 6 and 7, Japanese forces landed on and took over Kiska Island and Attu Island.

The Japanese attacks caused only minor damage to Dutch Harbor, which was quickly fixed. After this, Fort Glenn Army Air Base became the main forward base for launching bombing attacks against the Japanese forces on Kiska and Attu. Many different bomber and fighter squadrons were stationed at Fort Glenn to help with these attacks.

By the end of 1942, Fort Glenn AAB had over 10,000 people assigned to it. However, its role as a main advance air base changed in early 1943. New air bases were built further west on Adak and Amchitka Island. This meant Fort Glenn became less important for direct attacks. Its main job then became providing housing and services for soldiers and planes passing through.

Closing Down

After World War II ended, Fort Glenn stayed open for a while. It was used as a refueling stop for planes traveling across the Pacific Ocean, especially for Military Air Transport Service flights from Japan to the United States. The main runway was even made longer, to 8,300 feet, to handle bigger, long-range aircraft. By 1946, only a small number of staff remained because many soldiers were sent home after the war.

The last Air Force personnel left by September 30, 1947. The base was then put on inactive status and was mostly abandoned. It was officially closed in 1950. Between 1952 and 1955, the land was given to the Bureau of Land Management. Later, parts of the land were transferred to different owners, including Alaska Native groups and the State of Alaska.

Today, hundreds of old buildings, runways, and World War II artillery positions are still there, slowly falling apart. Fort Glenn AAF is now like a ghost town. However, a family of cattle ranchers lives there and has fixed up some of the old World War II buildings. The large size and untouched nature of the site make Fort Glenn AAF a great example of how historical landscapes can be preserved.

In 1991, historians from the National Park Service visited the site. They looked at the World War II buildings, structures, and the overall landscape. They decided that any environmental cleanup should focus on removing dangerous items like loose wires, transformers, hazardous waste, and old bombs. Non-dangerous World War II items, like empty barrels, could be left in place. All other buildings and structures, even if they looked "ugly," would be left alone and preserved. This means letting them remain as they are, as part of the historical landscape.

On July 12, 2008, nearby Mount Okmok erupted. It sent ash 50,000 feet into the air and forced the ranch residents to leave. The eruption destroyed almost all remains of the South Pacifier Emergency landing strip. However, some signs of it can still be seen in aerial pictures.