Castell Caer Seion facts for kids

Castell Caer Seion at the summit of Conwy Mountain

|

|

| Alternative name | Castell Caer Lleion, Castell Caer Leion, Conwy Mountain Hillfort, Sinnodune |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 53°16′57″N 3°51′44″W / 53.282512°N 3.862296°W |

| OS grid reference | SH 75938 77782 |

| Altitude | 244 m (801 ft) |

| Type | Hillfort |

| Width | 95 m (310 ft) |

| Volume | 30351 m² (326699 f²) |

| Diameter | 326 m (1069 ft) |

| History | |

| Material | Stone, earth |

| Founded | 6th–4th centuries BC (first phase), 3rd century BC (second phase) |

| Abandoned | 2nd century BC |

| Periods | Iron Age |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1906, 1909, 1951, 1952, 2008 |

| Archaeologists | H. Picton, W. Bezant Lowe, W .E. Griffiths & A. H. A. Hogg, George Smith |

| Condition | Ruined, but good. |

| Management | Cadw |

| Public access | Yes |

| Designation | Scheduled Ancient Monument |

Castell Caer Seion is an ancient hillfort from the Iron Age. It sits on top of Conwy Mountain in Conwy County, North Wales. This fort is special because it has a smaller, very strong fort built inside a larger one. There was no clear way to get between the two forts.

Archaeologists don't know exactly when the first fort was built. But recent digs show people lived there as early as the 6th century BC. The smaller fort was likely built around the 4th century BC. People lived in both forts at the same time until about the 2nd century BC. The bigger fort had about 50 roundhouses, which were circular homes. The smaller fort had only about six. This site is now protected by law as a scheduled ancient monument.

Contents

What is Castell Caer Seion?

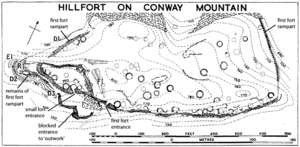

This hillfort is on a ridge of rock called rhyolite. It is about 244 meters (800 feet) high. A single wall, called a rampart, surrounds the main fort. The western part has a smaller, more protected area with stronger defenses. The northern side of the ridge is very steep, so it was naturally protected. This meant no outer wall was needed there at first.

The smaller fort was built inside the larger one around the 4th century BC. It had thick stone walls all around it. There were also defensive ditches on its eastern and north-eastern sides. A defensive structure was also built to the southeast. The fort offers amazing views of Conwy Bay. It is also near an old trackway that followed the coast. The whole fort covers about 3 hectares (7.5 acres). It is about 326 meters (1,069 feet) long. At its widest, it is about 95 meters (310 feet) from the southern walls to the cliffs.

Why does Castell Caer Seion have so many names?

The name 'Caer Seion' is thought to be the oldest and most real name for the hillfort. Records show this name goes back to the 9th century. The name 'Castell Caer Lleion' likely came from a mistake in translation in the late 1600s.

The words 'Castell Caer' actually mean "Castle Fort." This is a bit like saying "ATM Machine" – it repeats itself! Because there isn't one official name, the site is called many things. These include 'Caer Seion', 'Castell Caer Seion', 'Castell Caer Lleion', 'Castell Caer Leion', and 'Conwy Mountain hillfort'. An even older name, 'Sinnodune', was recorded in the 1530s but is not used anymore.

What have archaeologists found at Castell Caer Seion?

Archaeologists have dug at the site three main times. These digs happened in 1906 and 1909, then in 1951 and 1952, and finally in 2008. For a long time, it was hard to figure out exact dates because they didn't find many items that could be dated. But newer methods have helped scientists date the earliest known time people lived there.

First digs: 1906 and 1909

The first digs were done by Harold Picton and W. Bezant Lowe. They started in 1906 and finished in 1909. They didn't find much, but they were the first to find sling stones and a rubbing stone. Sling stones were used as weapons. Bezant Lowe also thought there might be a curved defense near the entrance to the smaller fort. In one of the huts, they found a stone floor. It was mostly messy, but one part was neatly put together.

Second digs: 1951 and 1952

The biggest digs were done by W.E. Griffiths and A.H.A. Hogg. Most of what we know about the site today comes from their work. They believed the fort was built in two main stages during the later Iron Age. They were the first to suggest that both forts were used at the same time. They thought people might have used a movable ladder to get between the two forts.

Third dig: 2008

The 2008 dig was smaller but very important. It helped archaeologists get exact dates for when people lived in the forts. George Smith led this dig. His team used radiocarbon dating on charcoal found at the site. This showed that the original fort was used between the 6th and 4th centuries BC. The smaller fort was built around the 4th century BC.

These studies also suggested the fort was left empty before the 2nd century BC. This means it was probably not destroyed by the Roman invasion of Wales in 48 AD, as some people thought. By studying pollen, grain, and wood, they also learned about what the people ate and what the land looked like back then.

Homes at the Fort

Archaeologists have only dug up a few of the more than 50 roundhouses that were once at the site. These roundhouses were homes. The way they were built and the materials used were similar throughout the fort's history. This is different from other sites that were used during the Roman period, where you often see many different styles of homes.

The roofs of the huts did change over time. The older huts (Huts 1 and 3) had few post holes, suggesting a wigwam-like roof. A hut from a later period (Hut 4) showed signs of internal posts, meaning a different roof style. Many huts were built along a terrace behind the main southern wall. This location likely protected the people from the wind.

Entrances to the Fort

Archaeologists found three clear entrances at the site. They also thought there might be a fourth, but it wasn't confirmed. Only the main entrance to the older fort was fully studied. The other two were mostly cleared and mapped.

Main Entrance

The main entrance was in the southern wall, near Hut 1. It was about 5 meters (17 feet) long and 2.6 meters (8.6 feet) wide at its narrowest. It seems the entrance was once paved, but the stones have worn away. Large, flat stones supported the thick wall at the entrance. These stones were hidden underground.

Four large, square holes found at the entrance likely held wooden posts. These posts probably supported a wooden bridge over the gate. The gate itself was about 1.8 meters (6 feet) wide, so it could have been a single door.

Entrance to the Smaller Fort

Not much is known about the entrance to the smaller fort because it hasn't been fully dug up. However, large square post holes, like those at the main entrance, were found. This suggests they served a similar purpose. The main difference was where they were located. These post holes were around the corner of the passage, against the inner wall.

Outwork Entrance

The third entrance was in a defensive structure at the southeast of the site. This entrance was about 5.8 meters (19 feet) wide and 7 meters (23 feet) long. It was built between the overlapping ends of the ramparts. It was lined with large, flat stones called orthostats. Some of these stones were very big, like megaliths. Part of the north side had fallen, blocking the entrance. Archaeologists think it must have looked very impressive when it was new.

Fort Defenses

The main defenses of both forts were stone walls. Sometimes, these walls had a ditch on the outside. The larger fort stayed mostly the same over time. It had a single wall that protected it on the three sides that were easy to attack. The smaller fort was built in two stages and was much stronger. Its first version was bigger and more complex. The defenses of the small fort were unusual for Iron Age hillforts. They were built to defend against attacks from inside the main fort, as well as from outside.

Main Wall

The main wall surrounded the fort on the east, south, and west sides. It followed the best natural path for defense along the hilltop. The outer part of this wall on the south side was very ruined. It was about 3 meters (10 feet) thick and made of large stones. The inner part was made of both laid stones and large slabs. Near the main entrance, the wall was double-faced. Further east, the outer wall was well-preserved and had a batter, meaning it sloped inwards for stability.

The steep cliffs to the north and northeast meant no extra defenses were needed there. But where the slope was gentler to the northwest, there were remains of a wall. This wall was very ruined and covered in grass. Archaeologists also noted an extra defensive ditch along its outside (marked as D1 on the map). This ditch continued to the southwest, around a rocky area (D2).

Small Fortress Defenses

The south wall of the small fort was wider than the main wall, about 3.6 to 4.8 meters (12–16 feet) thick. It was built of laid stones. An extra defensive wall outside the small fort's southwest wall ended at a rock outcrop (R1 on map). The ditch from the main fort's northwest wall continued around this wall. Where it went around the western outcrop, there was clear evidence of a smaller, extra ditch (E1). The larger ditch continued along the south wall of the smaller fort, ending just before the defensive outwork (D3). Inside the large fort, parallel to the eastern wall of the small fort, was another bank-and-ditch defense (F1).

Outwork Defenses

The outwork was built differently from the other walls. It had large, flat blocks on its outer face, or slabs on edge near the entrance. The inside was filled with small stones and earth.

Huts and Defenses

Two huts were likely connected to the fort's defenses. Hut 1 was just inside the main entrance. Another hut next to Hut 3 was also in a key defensive spot. In Hut 1, archaeologists found 612 sling stones. Half of these were neatly stacked against the wall, suggesting they were stored for defense. More sling stones were found near the hut next to Hut 3, supporting this idea.

What did people find inside the fort?

Archaeologists found many small items at the site. These helped them figure out that the fort was from the Iron Age, even without finding much pottery.

Some important finds include:

- 1,141 sling stones: These were smooth, oval beach pebbles, 2.5 to 5 cm (1–2 inches) long. About half were found in a neat pile in a hut.

- Possible iron tweezers

- A rare lignite spindlewhorl: This was used for spinning thread.

- A small piece of corroded iron: This might have been a lancehead or a knife.

- Stone spindlewhorls

- Four saddle querns: These were stones used for grinding grain.

- Rubbing stones and hones (whetstones): Used for sharpening.

- Pot boilers: Stones heated and dropped into water to cook food.

- Bones: Fragments of ox, horse, and sheep bones were found.

What was the environment like?

Studies of pollen showed that the area around the fort was mostly heath and grass. This is similar to how it looks today. Pollen and charcoal analysis also suggest that there was a woodland nearby. This woodland likely had hazel, birch, and alder trees.

Images for kids

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |