Charles Hodge facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Hodge

|

|

|---|---|

Hodge, circa 1850–60

|

|

| 2nd Principal of Princeton Theological Seminary | |

| In office 1851–1878 |

|

| Preceded by | Archibald Alexander |

| Succeeded by | Archibald Alexander Hodge |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 27, 1797 |

| Died | June 19, 1878 (aged 80) |

| Spouses | Sarah Bache (married 1822; died 1849) Mary Hunter Stockman (married 1852) |

| Children | Archibald Alexander Hodge, Caspar Wistar Hodge Sr. |

| Parents | Hugh Hodge Mary Blanchard |

| Alma mater | Princeton College Princeton Theological Seminary |

| Signature | |

Charles Hodge (born December 27, 1797 – died June 19, 1878) was an important Presbyterian leader and theologian. He was the principal of Princeton Theological Seminary from 1851 to 1878.

Hodge was a key supporter of the Princeton Theology, a type of Calvinist thinking popular in America in the 1800s. He strongly believed that the Bible was the true Word of God. Many of his ideas were later used by groups like Fundamentalists and Evangelicals in the 1900s.

Contents

Biography

Charles Hodge's father, Hugh, was the son of a Scotsman who came to America from Northern Ireland in the early 1700s. Hugh graduated from Princeton College in 1773. He worked as a military surgeon during the American Revolutionary War and later as a doctor in Philadelphia.

Hugh married Mary Blanchard in 1790. Sadly, their first three sons died from yellow fever epidemics. Their first son to survive childhood, Hugh Lenox, was born in 1796. Charles was born on December 27, 1797. His father died seven months later from yellow fever. Charles and his brother were raised by relatives, some of whom were wealthy. Their mother, Mary, also took in boarders to help pay for their schooling. She made sure they received a good Presbyterian religious education.

In 1812, Charles moved to Princeton to attend Princeton College. This school was originally set up to train Presbyterian ministers. At the same time, Princeton Theological Seminary was created as a separate school to train ministers. This was because the church felt the college wasn't doing enough to prepare ministers.

College and Seminary Life

At Princeton, the first president of the new seminary, Archibald Alexander, took a special interest in Charles Hodge. Alexander helped him with Greek and took him on preaching trips. Hodge later named his first son after Alexander. Charles became good friends with other future leaders, including John Maclean, Jr., who would become president of Princeton College.

In 1815, during a time of strong religious feeling among students, Hodge joined the local Presbyterian church. He decided to become a minister. He entered the seminary in 1816. The studies were very tough. Students had to read the Bible in its original languages and study old Latin theology books.

After graduating in 1819, Hodge continued to study Hebrew. He began preaching as a missionary in 1820. Later that year, he became an assistant professor at Princeton Seminary, teaching biblical languages. In 1821, he became a minister. In 1822, he became a full Professor of Oriental and Biblical Literature. That same year, he married Sarah Bache, who was Benjamin Franklin's great-granddaughter.

Studies in Europe

Hodge felt he needed more education, so he traveled to Europe from 1826 to 1828. He studied in Paris, Halle, and Berlin. He learned French, Arabic, Syriac, and German. He also met important theologians like Friedrich Schleiermacher. Hodge admired the deep learning in Germany. However, he felt that some of the new ideas there were too focused on philosophy and moved away from common sense. Unlike some other American theologians who studied in Europe, Hodge's trip did not change his strong commitment to his faith.

Starting in the 1830s, Hodge had a painful leg problem. From 1833 to 1836, he had to teach his classes from his home. He continued to write articles for the Biblical Repertory, which was later renamed the Princeton Review. In the 1830s, he wrote a major commentary on the Book of Romans.

In 1840, he became Professor of Didactic Theology, but he also kept teaching New Testament studies until he died. In 1846, he was chosen as the leader (Moderator) of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church. Hodge's wife died in 1849. After the deaths of his colleagues Samuel Miller and Archibald Alexander, he became the most senior professor at the seminary. He was seen as the main leader of the Princeton theology.

When he died in 1878, both friends and opponents recognized him as one of the most important debaters of his time. Three of his children became ministers. Two of them, Caspar Wistar Hodge, Sr. and A. A. Hodge, later taught at Princeton Theological Seminary.

Literary and Teaching Activities

Charles Hodge wrote many books and articles about the Bible and theology. He started writing early in his career and continued until his death. In 1835, he published his Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans. This book is considered his most important work on interpreting the Bible.

Other important books he wrote include:

- Constitutional History of the Presbyterian Church in the United States (1840)

- Way of Life (1841), which was very popular and translated into other languages.

- Commentaries on the books of Ephesians, First Corinthians, and Second Corinthians.

His biggest work was the Systematic Theology (1871–1873), which was three volumes long and had over 2,200 pages. This book explained his entire system of Christian beliefs. His last book, What is Darwinism?, came out in 1874. He also wrote over 130 articles for the Princeton Review.

Hodge's writings and teaching had a huge impact. About 3,000 ministers studied under him. He was known as a great teacher, Bible interpreter, preacher, and debater. He was especially good at leading discussions on Sunday afternoons, where he spoke clearly and logically, but also with great warmth.

Hodge's articles for the Princeton Theological Review showed his strong writing skills. Many of these articles are considered masterpieces of debate. They covered many topics, from basic Christian beliefs to church rules. He especially focused on questions about human nature and salvation.

All of his books are still in print today, more than a century after his death.

Character and Significance

Charles Hodge was deeply devoted to Christ. This was the most important part of his own faith and how he judged others' faith. Even though he was a Presbyterian and a Calvinist, he had a broad view of Christianity. He did not agree with those who had very narrow ideas about church rules.

Hodge was naturally a conservative person. He spent his life defending the Reformed theology as it was explained in the Westminster Confession of Faith and the Westminster Shorter Catechism. He often said that Princeton never came up with a new idea. This meant that Princeton supported the traditional Calvinist beliefs, not newer, changed versions.

Hodge is remembered as one of the great defenders of the Christian faith. He was not trying to start a new era of thought. Instead, he was a champion of his church's beliefs throughout his long life. He was a trusted leader during difficult times and taught many ministers for over fifty years. His understanding of Christian faith and Protestantism is best seen in his Systematic Theology.

Views on Controversial Topics

Slavery

Charles Hodge was a very traditional thinker and believed the Bible was perfect and should be understood literally. Because of this, he believed that the idea of slavery itself had some support in certain parts of the Bible. He even owned enslaved people himself. However, he strongly spoke out against the mistreatment of enslaved people. He also pointed out that the laws in the Southern states were unfair. These laws stopped enslaved people from getting an education, having family rights, and protected them from abuse. He thought that improving these laws would be the first step towards ending slavery in the United States.

The Presbyterian Church in 1818 had a similar view. They said that slavery in the U.S., while not always a sin, was a sad situation that should eventually change. Like the church, Hodge tried to find common ground between those who wanted to end slavery (abolitionists) and those who supported it. He hoped to bring people together to eventually abolish slavery completely.

It's important to know that not all Christians who believed the Bible was perfect agreed with Hodge on slavery. Other Christian leaders in the 1800s, who also believed in the Bible's truth, spoke out against slavery as a "vast moral evil."

Old School Presbyterians

Hodge was a leader of the "Old School" group of Presbyterians when the Presbyterian Church (USA) split in 1837. This split happened because of disagreements over beliefs, church practices, and slavery. Before 1861, the Old School group generally avoided taking a strong stance against slavery, but it was still a big topic of debate between the Northern and Southern parts of the church.

Civil War

While Hodge could accept the idea of slavery, he could not accept what he saw as treason when the Southern states tried to leave the United States in 1861. Hodge was a strong supporter of the Union (the North). In January 1861, he wrote in the Princeton Review that leaving the Union was against the U.S. Constitution.

When the Civil War began, the Presbyterian General Assembly met in May 1861. They passed a resolution pledging support for the federal government. Hodge voted against this, believing the church should not get involved in political matters. Because of this resolution, the Presbyterian church officially split into Northern and Southern branches in December 1861.

Darwinism

In 1874, Hodge published a book called What is Darwinism?. In it, he argued that Darwinism, the theory of evolution by Charles Darwin, was essentially atheism (the belief that there is no God). To Hodge, Darwinism went against the idea that God designed the world, and therefore it seemed atheistic to him. He attacked Darwinism in his writings. His views shaped the position of Princeton Theological Seminary until his death in 1878. While he didn't think all ideas about evolution conflicted with religion, he was worried about it being taught in colleges.

Meanwhile, at Princeton University (a separate school), President John Maclean also rejected Darwin's theory. However, in 1868, a new president named James McCosh took over. McCosh believed that much of Darwinism could be proven true. He tried to help Christians prepare for this. Instead of seeing conflict between science and religion, McCosh looked for ways they could agree. He argued that Darwin's discoveries actually showed more evidence of God's plan and purpose in the universe. He believed Darwinism was not atheistic or against the Bible. So, Presbyterians in America had two different ways of thinking about evolution, both coming from Princeton. The Seminary followed Hodge's view for many years, while the university became a major center for the new science of evolutionary biology.

The debate between Hodge and McCosh showed a growing conflict between science and religion over Darwin's theory of evolution. However, both men also agreed on many things. They both supported the growing role of scientific study in understanding nature, but they resisted science trying to explain philosophy and religion.

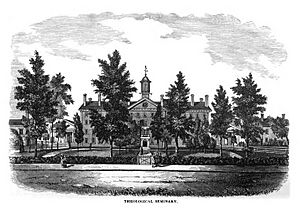

Images for kids

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |