Charles Oliver Brown facts for kids

Charles Oliver Brown lived a long and interesting life from 1848 to 1941. When he was just 11 years old, he worked driving a team on the canal from Toledo to Cincinnati. At 13, he became a bugler in the American Civil War. Later, he became a minister and a well-known speaker across the United States and Canada. He was also connected to General William Tecumseh Sherman's famous saying, "War is Hell." After the Civil War, Brown faced a difficult situation in San Francisco but overcame it. He became a popular speaker and was often quoted for his ideas on how Congregational churches grew.

Contents

Early Life in Ohio

Charles Oliver Brown was born in Battle Creek, Michigan, on July 22, 1848. When he was four, his family moved to Toledo, Ohio, where his father had a blacksmith shop. At the young age of 11, Charles worked driving a team of horses along the Miami and Erie Canal from Toledo to Cincinnati. He also attended the Toledo Grammar School.

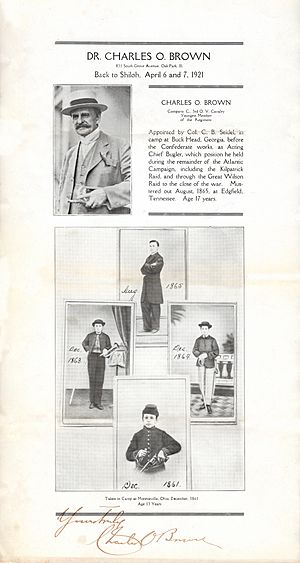

The "Boy Bugler" of Sherman's Army

When the American Civil War began in 1861, Charles's father, Major Oliver M. Brown, helped create a group of soldiers called Company C of the 3rd Ohio Cavalry. Charles Oliver Brown went to war with his father as a bugler. He was only 13 years old. He fought in 25 battles and was even wounded. This earned him the nickname, "The Boy Bugler" of Sherman's Army. By age 16, he was in charge of the regiment's 26 buglers. This made him the youngest chief bugler in the Union army at that time.

Young Brown played the bugle call that sent 3,000 soldiers into battle at the Battle of Lovejoy's Station. This happened during General Sherman's push in the Atlanta Campaign. At the Battle of Selma, he bravely carried a message through heavy gunfire. Because of this brave act, Congress later voted to increase his pension. The young bugler was also part of the important mission that captured the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis.

Brown officially joined the Union Army on February 18, 1864, when he was 16. His father signed a special paper allowing him to join since he was a minor. Charles joined as a musician and received an advance payment and a bounty. Proof of his early service can be found in a photo of him in uniform with a pistol. Also, a history book about the 3rd Ohio Cavalry mentions him. It says he was with the regiment at 13, learned to play the bugle, and became a regimental bugler.

Becoming a Minister

In 1871, Brown enrolled in Olivet College. During his time there, he taught subjects like penmanship and bookkeeping. In his final year, he also taught Greek. He earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in June 1875.

After college, Charles Oliver Brown became a pastor. He led the Congregational church in Rochester, Michigan, starting in September 1876. From 1880 to 1885, he served at the Congregational Church of Galesburg, Michigan. He also taught at Olivet College and was the pastor of the First Congregational Church of Kalamazoo, Michigan.

"If Nominated, I Will Not Run"

Dr. Brown was a Republican his whole life. He almost became a United States senator for Iowa while living in Dubuque. In those days, state lawmakers chose senators. Friends asked him to run for the job. He said he had a job he was good at and didn't try to win the election. Even so, he was nominated and only lost by three votes.

From Dubuque, Dr. Brown moved to Tacoma, Washington, to lead a church. Later, he was asked to become the pastor of the biggest Congregational church on the Pacific coast in San Francisco. He accepted this new role and resigned from his Tacoma church. Meanwhile, his friends in Tacoma were getting ready to nominate him for governor of the state. Even though they told him he would likely win, he refused to change his mind and went to San Francisco. This story connects Brown to another famous quote by General William Tecumseh Sherman: "If nominated, I will not run. If elected, I will not serve."

Facing Challenges

While Charles Oliver Brown was a pastor in San Francisco, he faced some difficult challenges. His character was questioned due to an attempted scheme involving a woman from his church. This became a big news story. He denied the accusations, and there were strong disagreements within the church. In April 1896, the situation became so tense that he resigned. His supporters tried to keep the church going, but their plans ran into problems. Brown then took a vacation and accepted a new position in Chicago.

It seems Brown was cleared of the charges. A newspaper reported that he "came through his trials all right." The person who made the accusations later confessed that it was a plan to trick the minister.

Writing History

Brown was part of a group that wrote and published The History of The Third Ohio Cavalry. This book gives a great account of what a typical Civil War cavalry regiment was like. It even includes poems written by soldiers from the regiment. Here are some lines from Brown's poem, My Bugle:

Reveille in early morning,

Say at four o'clock or three, That was not the same exactly, For you comrades, or for me.

Oft' I saw you coatless, hatless, Sometimes pantless tumble out, When the orderly was shouting, "Roust about, men; roust about!"

And the bugler, like an umpire Of a modern baseball game, Sometimes had to dodge the missiles,

And keep sounding just the same.—History of the 3rd Ohio Cavalry, p. 214.

Author and Speaker

At one point, Charles Oliver Brown was the vice president of La Salle Extension University, which he helped start. He was also one of the first speakers for the Chautauqua movement, which offered educational programs. He was so popular that he could travel all year long giving speeches. He wrote two books: one called "Evidences of Christianity" and another called "Labor and Its Troubles."

Remembering the Civil War

After the American Civil War ended, Brown became very active in the Grand Army of the Republic, a group for Civil War veterans. He often attended reunions with other veterans. Brown and his wife, May, went to the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. There, President Franklin Roosevelt dedicated the Peace Memorial. In 1940, a year before he passed away, Brown was one of a few Civil War veterans invited to see the movie Gone with the Wind in Chicago. Not many veterans who fought in the war lived long enough to see the movie.