Chautauqua facts for kids

Chautauquas (say shə-TAW-kwə) were a popular way for adults to learn and have fun in the United States, especially from the late 1800s to the early 1900s. These events grew and spread across the countryside until the mid-1920s. Chautauquas brought entertainment and education to whole communities. They featured speakers, teachers, musicians, performers, preachers, and experts of the time. Former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt even called Chautauqua "the most American thing in America."

Contents

History of Chautauquas

Chautauquas were like traveling schools and entertainment shows. They offered a mix of learning, music, and talks for everyone.

The First Chautauquas

The very first Chautauqua started in 1873 at Lakeside Chautauqua on Ohio's Lake Erie. It was created by a group called the Methodists.

The next year, in 1874, the New York Chautauqua Assembly began. It was organized by a Methodist minister named John Heyl Vincent and a businessman named Lewis Miller. They set it up at a campsite by Chautauqua Lake in New York state. A few years before, Vincent, who edited a Sunday School magazine, had started training Sunday school teachers outdoors in the summer. These gatherings became very popular. The organization Vincent and Miller founded later became known as the Chautauqua Institution. Many other Chautauquas started up in a similar way.

The idea of a summer camp for learning became very popular for families. Many other Chautauquas copied this style. Within ten years, "Chautauqua assemblies" (or just "Chautauquas") popped up all over North America. They were named after the original spot in New York. The Chautauqua movement, which began in the 1870s, was similar to the earlier Lyceum movement from the 1840s. As Chautauqua groups started competing for the best performers, lyceum agencies helped them book acts. Today, Lakeside Chautauqua and the Chautauqua Institution are still very big and attract thousands of people each summer.

Independent Chautauquas

Independent Chautauquas were like permanent versions of the New York Chautauqua Institute. They usually had their own buildings or rented places like amusement parks. These Chautauquas were often built in nice, quiet spots just outside a town that had good train service. In the 1920s, when Chautauquas were most popular, there were hundreds of these independent groups. However, their numbers have gone down since then.

Circuit Chautauquas

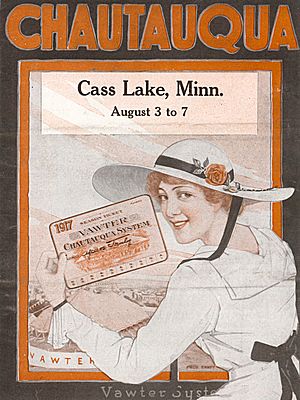

"Circuit Chautauquas" were also called "Tent Chautauquas." These were traveling shows that moved from town to town. They were started by Keith Vawter and Roy Ellison in 1904. At first, they didn't do well, but by 1907, their idea became very successful. The shows would happen in large tents set up "on a good field near town." After a few days, the Chautauqua would pack up its tents and move to the next place. Keith Vawter is known for organizing these traveling Chautauqua series.

Not everyone liked the tent Chautauquas. Some people thought they made the original Chautauqua idea less special. For example, Frank Gunsaulus told Keith Vawter, "You're ruining a splendid movement. You're making Chautauqua cheap."

In Vawter's plan, each performer or group had a specific day in the program. For instance, the "first-day" performers would move to the next Chautauqua, followed by the "second-day" performers, and so on. This continued throughout the touring season. By the mid-1920s, circuit Chautauquas were at their peak. They visited over 10,000 communities and reached more than 45 million people. However, by about 1940, they had mostly disappeared.

Lectures and Speeches

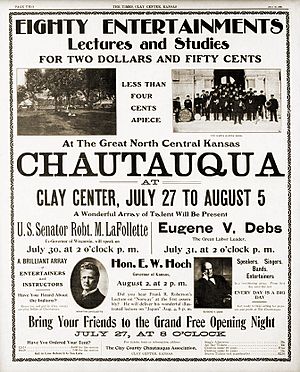

Lectures were a main part of the Chautauqua experience. Before 1917, talks were the most important part of the circuit Chautauqua programs. Until 1913, the two main types of lectures were speeches about making things better and inspiring talks. Later, topics included current events, travel stories, and often funny tales.

Famous Speakers

One of the most frequent speakers was Russell Conwell. He gave his famous "Acres of Diamonds" speech 5,000 times to audiences at Chautauqua and Lyceum events. His message was that people should work hard and become successful, so they could use their wealth to do good things.

Maud Ballington Booth, known as the "Little Mother of the Prisons," was another popular speaker. Her stories about life in prisons often made her audiences cry and inspired them to push for changes. Jane Addams spoke about social problems and her work at Hull House, a place that helped immigrants and poor people. Helen Potter was also a notable woman in Chautauquas. She performed many different roles, acting as both men and women. Her performances were known for their variety and how believable she was in her different characters. Author Opie Read was loved by audiences for his stories and down-to-earth wisdom. Other well-known speakers included U.S. Representative Champ Clark, Missouri Governor Herbert S. Hadley, and Wisconsin Governor "Fighting Bob" La Follette.

Religious Programs

Christian teaching, preaching, and worship were a strong part of the Chautauqua experience. Even though the Chautauqua movement was started by Methodists, it was open to all faiths from the beginning. Important Catholics like Catherine Doherty took part. In 1892, a Lutheran Church leader named Theodore Emanuel Schmauk helped organize the Pennsylvania Chautauqua.

Early religious talks at Chautauqua were usually general and focused on good morals. Later, in the early 1900s, more sermons and lectures focused on Fundamentalism, a strict form of Christianity. However, because there were so many Chautauquas and no single group controlled them, religious programs varied a lot. Some were very religious, almost like church camps. Others were more secular (non-religious) and were more like summer schools or even competed with vaudeville shows, which had animal acts and trapeze acrobats.

For example, Lakeside Chautauqua is privately owned but connected to the United Methodist Church. In contrast, the Colorado Chautauqua is completely non-religious and mostly secular.

Chautauqua and Vaudeville

In the 1890s, both Chautauqua and vaudeville shows were becoming very popular. Chautauqua started from Sunday school ideas and valued good morals and education. Vaudeville, however, came from minstrel shows and variety acts and often had rougher humor. Because of their different beginnings, the two movements were often at odds.

Chautauqua was seen as wholesome, family entertainment. It appealed to middle-class people and those who wanted to be seen as respectable. Vaudeville, on the other hand, appealed more to working-class men. There was a clear difference between them, and they usually didn't share performers or audiences.

As the 1900s began, vaudeville managers tried to make their shows more "refined." At the same time, Chautauqua became more open to different types of acts. Slowly, as vaudeville became more respectable, the lines between the two types of entertainment started to blur.

Music at Chautauqua

Music was a very important part of Chautauqua, especially band music. John Philip Sousa's student, Bohumir Kryl's Bohemian Band, often performed on the circuit. One of their popular acts was the "Anvil Chorus" from an opera called Il Trovatore. It featured four strong drummers hitting anvils, making sparks fly across the dark stage with special effects.

Spirituals (religious songs, often from African-American traditions) were also popular. White audiences liked seeing African-Americans perform something other than minstrel shows. Other musical groups included the Jubilee Singers, who sang a mix of spirituals and popular songs. There were also other singers and instrumental groups like the American Quartette, who played popular music, ballads, and songs from different countries. Performers like Charles Ross Taggart, known as "The Man From Vermont," played the violin, sang, did ventriloquism and comedy, and told funny stories about life in rural New England.

Opera became part of the Chautauqua experience in 1926. The American Opera Company, from the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, started touring the country. By 1929, a permanent Chautauqua Opera company was created.

Politics and Chautauqua

Chautauquas were connected to the political changes happening in the late 1800s. Groups like the "Populist Party" spoke out against political corruption and supported everyday people against the rich and powerful. Other popular political topics in Chautauqua lectures included the temperance (reducing or stopping alcohol use), women's suffrage (women's right to vote), and child labor laws (rules to protect children working).

However, the Chautauqua movement usually avoided taking strong political sides. Instead, they invited public officials from all major political parties to give talks. This made sure the program was balanced for everyone attending. For example, in 1936, during the year of a presidential election, visitors at the Chautauqua Institution heard speeches from Franklin D. Roosevelt, his Republican opponent Alf Landon, and two third-party candidates.

Traveling Chautauqua Shows

Here is an example of a route taken by a group of Chautauqua performers, the May Valentine Opera Company. They performed the opera The Mikado during their 1925 summer season. They started on March 26 in Abbeville, Louisiana, and finished on September 6 in Sidney, Montana.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |