Charles Richter facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Richter

|

|

|---|---|

Charles Richter, c. 1970

|

|

| Born |

Charles Francis Richter

April 26, 1900 Overpeck, Ohio, U.S.

|

| Died | September 30, 1985 (aged 85) Pasadena, California, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | Stanford University California Institute of Technology |

| Known for | Richter magnitude scale Gutenberg–Richter law Surface-wave magnitude |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Seismology, physics |

| Institutions | California Institute of Technology |

Charles Francis Richter (born April 26, 1900 – died September 30, 1985) was an American scientist. He was a seismologist, someone who studies earthquakes, and a physicist. Richter is famous for helping create the Richter magnitude scale. This scale was used for a long time to measure how big earthquakes were. He developed it with Beno Gutenberg in 1935. They both worked at the California Institute of Technology.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Richter was born in Overpeck, Ohio, in the United States. His family moved to Los Angeles in 1909. After finishing high school, he went to Stanford University. He earned his first degree there in 1920.

In 1928, he started working on his advanced degree in physics. This was at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). But before he finished, he got a job offer. It was at the Carnegie Institute of Washington.

At this new job, he became very interested in seismology. This is the study of earthquakes and the waves they make. He then worked at the Seismological Laboratory in Pasadena. There, he worked with a scientist named Beno Gutenberg.

In 1932, Richter and Gutenberg created a way to measure earthquakes. This became known as the Richter scale. In 1937, Richter returned to Caltech. He stayed there for the rest of his career. He became a professor of seismology in 1952.

Richter's Career in Seismology

Charles Richter started working at the Carnegie Institution of Washington in 1927. He began working with Beno Gutenberg there. The Seismology Lab at Caltech needed a way to measure earthquake strength. They wanted to publish regular reports on earthquakes in southern California.

Richter and Gutenberg created a scale to meet this need. It became known as the Richter scale. It measured how much the ground moved during an earthquake. This idea came from another scientist, Kiyoo Wadati.

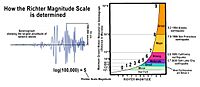

They designed a special tool called a seismograph. This tool measured the ground's movement. They also developed a special kind of scale. It was a logarithmic scale, which means each step is ten times bigger than the last.

Richter chose the name "magnitude" for this measurement. He had been interested in astronomy as a child. Astronomers use "magnitude" to describe how bright stars are. Gutenberg helped a lot with the scale. But he didn't like interviews, so his name was left off the scale.

After the scale was published in 1935, scientists quickly started using it. It became the main way to measure earthquake strength. Richter stayed at the Carnegie Institution until 1936. Then he got a job at Caltech, where Gutenberg also worked.

Gutenberg and Richter wrote a book together in 1941. It was called Seismicity of the Earth. A new version came out in 1954. This book is still an important guide in the field of seismology.

Richter became a full professor at Caltech in 1952. In 1958, he published another important book. It was called Elementary Seismology. This book was based on his notes from teaching students. Many people think it was his most important work.

Later in his career, Richter helped with earthquake engineering. He worked on creating building codes for areas where earthquakes happen often. In the 1960s, the city of Los Angeles removed many decorations from buildings. This was because of Richter's warnings. He helped prevent many deaths during the 1971 San Fernando earthquake. Richter had retired in 1970.

Understanding the Richter Scale

Before Richter and Gutenberg, there was another way to rate earthquakes. It was called the Mercalli scale. This scale was created in 1902. It used Roman numerals from I to XII. It described how buildings and people reacted to the shaking.

For example, a small shake that made a light swing might be a I or II. A very strong earthquake that destroyed buildings would be an X. The problem with the Mercalli scale was that it was not exact. It depended on how strong buildings were or how used to earthquakes people were. It was also hard to rate earthquakes in empty areas.

The scale Richter and Gutenberg created was different. It was an exact way to measure an earthquake's strength. Richter used a seismograph to do this. A seismograph is a machine with a roll of paper and a pen. The pen records the ground's movement during an earthquake. The scale also considers how far the seismograph is from the epicenter. The epicenter is the spot on the ground directly above where the earthquake starts.

Richter chose the word "magnitude" because of his interest in astronomy. Stargazers use "magnitude" to describe how bright stars are. Gutenberg suggested that the scale should be logarithmic. This means that an earthquake of magnitude 7 is ten times stronger than a 6. It is a hundred times stronger than a 5. And it is a thousand times stronger than a 4. For example, the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake was a magnitude 6.9.

The Richter scale was published in 1935. It quickly became the main way to measure earthquake strength. At first, Richter didn't seem to mind that Gutenberg's name wasn't included. But later, after Gutenberg had passed away, Richter insisted that his colleague should get credit. Gutenberg had helped make the scale work for earthquakes all over the world. Since 1935, other ways to measure earthquake strength have also been developed.

Later Life and Legacy

Charles Richter died on September 30, 1985. He was 85 years old. He passed away in Pasadena, California. He is buried in Altadena, California's Mountain View Cemetery. Richter's work changed how we understand and prepare for earthquakes.

See also

In Spanish: Charles Francis Richter para niños

In Spanish: Charles Francis Richter para niños