Cincinnati riots of 1841 facts for kids

The Cincinnati riots of 1841 happened in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States. This was after a long dry spell caused many people to lose their jobs. Over several days in September 1841, white people who were out of work attacked black residents. The black residents fought back to defend themselves. Many black people were then gathered up and held in a protected area, and later moved to jail. The authorities said this was to keep them safe.

Contents

Why the Riots Happened

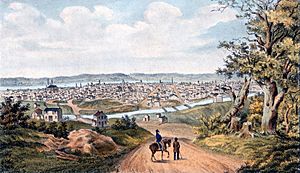

By 1840, Cincinnati had grown a lot. It was the sixth largest city in the U.S. It was a busy city with both rich areas and poor, crowded neighborhoods. Many people from Europe and black people from the South moved there for job chances.

Many city leaders wanted to keep good relationships with the slave-owning states south of the Ohio River. They did not like abolitionists (people who wanted to end slavery) or black people. Even though Ohio was a free state, its laws made it hard for black people. They could not vote. The state also had "Black Laws" from 1804 and 1807. These laws added more rules. For example, black children could not go to public schools. But black property owners still had to pay taxes to support these schools. Black people moving to Ohio had to register and pay a fee. They could not be on a jury or speak in court cases involving a white person. They also could not join the army.

The number of black people in Cincinnati grew from 690 in 1826 to 2,240 by 1840. The city also had many people from other countries, almost 40%. Irish immigrants often competed with black people for jobs and homes. As the city got more crowded, tensions grew. By 1850, Cincinnati had more black residents than any other city in the Old Northwest. Many black people found jobs on steamboats and along the river. By this time, many had become skilled workers or tradesmen, earning good money. Many also owned their own homes.

How Tensions Grew

On August 1, 1841, black leaders held events to celebrate the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. This law ended slavery in British colonies. Many white people did not like this celebration. That month, the city had a drought and a heat wave. The Ohio River got very low, which meant many men who worked on the river lost their jobs. These men were idle and hot, and they became angry and ready to argue.

Tensions increased, and there were several small fights between white and black people in their crowded neighborhoods. On the evening of Tuesday, August 31, a group of Irish men fought with some black people. The fight continued on Wednesday. A group of white men with clubs attacked a black boarding house. The fight spread to nearby homes and lasted almost an hour. Many people were hurt, but no one called the police. No one was arrested. Another fight happened on Thursday. Two white young men were badly hurt, possibly with knives. That day, angry groups of white people roamed the city. A witness said black people were "attacked wherever found in the streets." These attacks were so violent they could cause death.

The Main Attack: September 3rd

On Friday, there were rumors that bigger fights were planned. The Cincinnati Daily Gazette, which reported on the riots, did not mention any special police plans to stop trouble.

John Mercer Langston, who was twelve years old at the time, later became an important educator and politician. He said that black elders armed themselves with guns to plan their defense. They chose Major J. Wilkerson, a mulatto man, as their leader. Wilkerson was born a slave in Virginia in 1813. He bought his freedom and became an elder at the AME church in Cincinnati. This church was the first independent black church in the U.S.

Langston later said Wilkerson was a "champion of his people's cause." He would "maintain his own rights as well as those of the people he led." Wilkerson made sure women and children were moved to safe places. Then he placed the men in defensive spots on roofs, in alleys, and behind buildings.

An armed group, organized by people from Kentucky, gathered in Fifth Street Market. They carried clubs and stones. They marched toward Broadway and Sixth streets and destroyed a black-owned candy shop on Broadway. The crowd grew larger and ignored calls from city officials, including the mayor, to leave. When they moved to attack the black neighborhood, the mob was met with gunfire and had to retreat.

In more attacks, people on both sides were hurt, and some were reported killed. In the middle of the night, a group of white people brought a cannon. It was loaded with metal pieces and pointed down Sixth Street from Broadway. By this time, many black people had run away, but the fighting continued. The cannon was fired several times.

Around 2 a.m., soldiers arrived and stopped the fighting. The soldiers created a barrier around several blocks of the black neighborhood. They held the people inside captive. The soldiers also rounded up other black people in the city. They marched them into the blocked-off area. These people were held until they paid a fee.

After the First Attack: September 4th

Mayor Samuel W. Davies called a public meeting the next morning (Saturday) at the Court House. They met to discuss how to stop more violence. The meeting decided to find and arrest the black people who had hurt the two white boys. This group blamed the black community for the violence. But in truth, the black people had only defended themselves from large attacks by white people.

The mayor's group strongly criticized abolitionists. However, they promised not to allow mob violence. The authorities said they would take action to make unwanted black people leave the city. They said they would use the black law of 1807 and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 (laws about runaway slaves). They promised to protect African Americans and their property until they either paid a fee or left the city.

Black leaders met at Bethel AME church. They promised the mayor they would stay calm, stop lawbreaking, and not carry weapons. At a special City Council meeting, new rules were passed. They asked regular citizens, officers, watchmen, and firefighters to help keep the peace. They allowed the mayor to have up to five hundred deputies. They also called for the county soldiers to be used.

The soldiers and temporary police (some of whom might have been rioters) were sent throughout the city. They had orders to arrest every black man they found. Many black people had left the city for Walnut Hills to the north, or gone into hiding. But about 300 were rounded up and put in jail. A mob followed the prisoners to jail, making fun of them. Extra guards were brought in to protect the prisoners. Newspapers said that people from Kentucky could visit the jail to look for runaway slaves.

Even with these actions, city officials learned that the mob planned to attack again on Saturday night. The Mayor sent out peacekeeping forces. These included the military, firefighters, and authorized citizens. They also had a group of horses and several companies of volunteer soldiers.

The mob organized and split up to attack different parts of the city. They broke into the building that held the printing press of the Philanthropist newspaper. They broke the press and threw it into the river. They also broke into and destroyed several black-owned homes, shops, and a church. Finally, they left around dawn. The authorities arrested about forty people from the mob.

What Happened Next

The editor of the Cincinnati Daily Gazette said the riot could have been stopped earlier. He wrote, "A strong group of fifty or one hundred men would have scattered the crowd."

Langston said the mob's rioting was "the darkest and most terrible moment in Cincinnati's history."

Because of the damage from the riots, the black community started several self-help groups in the next few years. These included the United Colored Association, the Sons of Enterprise, and the Sons of Liberty. The writer Harriet Beecher Stowe lived in Cincinnati at the time. She was greatly affected by stories of violence she heard from people escaping the riot area.

Images for kids

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |