Climate change in New Zealand facts for kids

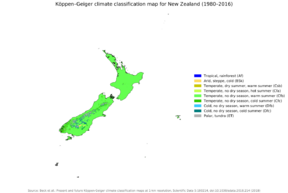

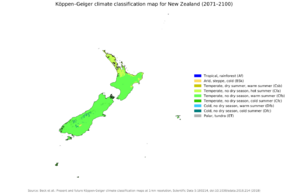

Climate change in New Zealand is about how the country's weather is changing, and what New Zealand is doing about it. Around the country, summers are getting longer and hotter. Some of New Zealand's famous glaciers have shrunk, and some have even melted away completely.

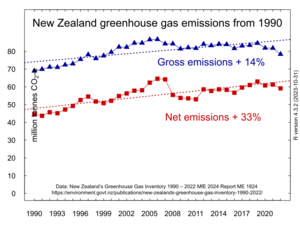

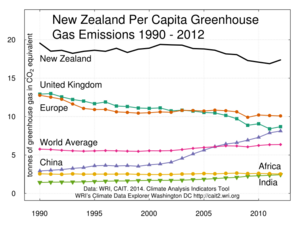

While New Zealand is a small country, it produces a significant amount of greenhouse gases for its size. This is mainly because of its large farming industry. On a per person (per capita) basis, New Zealand is one of the higher emitters among developed countries.

The government and people of New Zealand are responding to climate change in many ways. The country has an emissions trading scheme to help reduce pollution. In 2019, the government passed the Zero Carbon Act. This law created a Climate Change Commission to advise the government on how to lower emissions.

New Zealand has set some important goals. It aims to have net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and to plant one billion trees. In 2020, the Prime Minister declared a climate change emergency. This led to a promise that the government would become carbon neutral by 2025. This means buying electric cars for government use and making government buildings more environmentally friendly.

What are New Zealand's greenhouse gas emissions?

Greenhouse gases are gases in the Earth's atmosphere that trap heat. They are a bit like the glass in a greenhouse, which is where they get their name. The main greenhouse gases are carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane, and nitrous oxide.

New Zealand's mix of emissions is different from many other countries. This is because a large part of its economy is based on farming.

| NZ GHG Emissions Profile by Sector 2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sector | percent | |||

| Agriculture | 53% | |||

| Energy | 37% | |||

| Industry | 6% | |||

| Waste | 4% | |||

| NZ GHG Emissions Profile by Gas 2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| greenhouse gas | percent | |||

| Carbon Dioxide | 40% | |||

| Methane | 49% | |||

| Nitrous Oxide | 9% | |||

| HFCs PFCs and SF6 | 2% | |||

Where do the emissions come from?

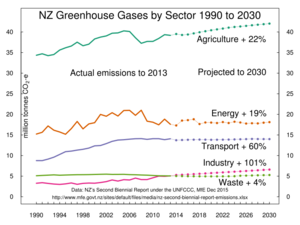

- Farming: Over half of New Zealand's emissions come from agriculture. This is mostly methane gas from sheep and cows. When these animals burp, they release methane. The use of fertilisers on farms also releases another greenhouse gas called nitrous oxide.

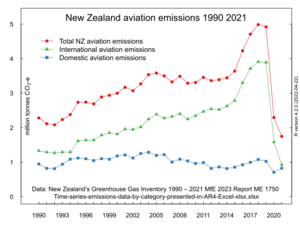

- Energy and Transport: About 37% of emissions come from the energy sector. This includes the fuel we use for cars, trucks, and planes. Because New Zealanders drive a lot and often use larger cars, transport is a big source of emissions.

- Industry and Waste: The rest of the emissions come from industrial processes and from waste breaking down in landfills.

Carbon Dioxide

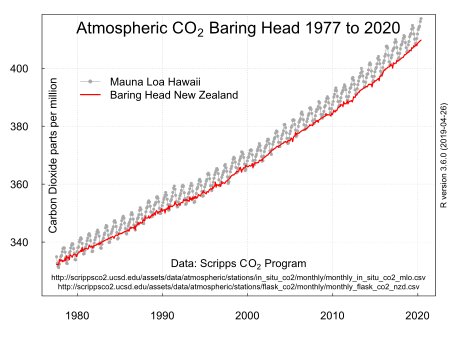

Scientists have been measuring carbon dioxide (CO₂) at Baring Head near Wellington since the 1970s. These measurements show that the amount of CO₂ in the air has been steadily increasing. This rise is similar to what has been seen in other parts of the world. Carbon dioxide mainly comes from burning fossil fuels like coal, oil, and gas for energy and transport.

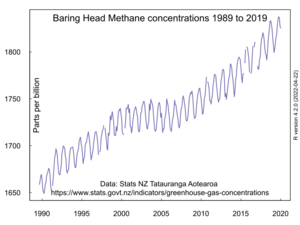

Methane

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas. In New Zealand, most methane comes from farm animals. Because New Zealand has millions of sheep and cattle, these emissions are very significant. Scientists are researching ways to reduce methane from livestock, such as by adding special seaweed to their food.

How is the environment changing?

Hotter weather

New Zealand's temperature has been rising. Records show that the country has warmed by about 1.37°C since 1909. The year 2022 was the warmest year ever recorded in New Zealand.

Scientists predict that temperatures will continue to rise. This will lead to more heatwaves and more extreme weather events like heavy rain and droughts. Hotter summers also increase the risk of wildfires, like the large Pigeon Valley fire near Nelson in 2019.

Effects on native wildlife

Climate change is a threat to New Zealand's unique plants and animals.

- Warmer temperatures can cause forests to produce large amounts of seeds, an event called a mast. This leads to a boom in the number of pests like rats and stoats, which then attack native birds like the kiwi.

- The tuatara, a special reptile, is also at risk. The temperature of the sand where its eggs are buried determines if the babies are male or female. Warmer nests mean more males will hatch, which could threaten the species' survival.

- Rising sea levels and storms can damage the coastal homes of seabirds like the hoiho (yellow-eyed penguin).

Melting glaciers

New Zealand has over 3,000 glaciers, but they are melting quickly. In the last 40 years, the total amount of ice in these glaciers has shrunk by about a third.

New Zealand's largest glacier, the Tasman Glacier, is retreating by about 180 metres every year. A large lake has formed at the bottom of the glacier as the ice melts. Scientists expect that one day, the Tasman Glacier will disappear completely. The loss of glaciers affects tourism and can also change the amount of water flowing into rivers, which is important for farming and electricity generation.

Rising sea levels

As the world gets warmer, ice sheets and glaciers melt, and the ocean water expands. This causes sea levels to rise. In New Zealand, this means that coastal communities are at greater risk of flooding and erosion. Low-lying areas in cities like Auckland, Wellington, and Dunedin could be regularly flooded in the future. This puts homes, roads, and important cultural sites like marae and urupā (burial grounds) at risk.

How does climate change affect people?

Farming and the economy

Farming is a huge part of New Zealand's economy. Climate change can make farming more difficult. More frequent droughts will mean less water for crops and animals, especially in eastern parts of the country. On the other hand, western regions might see more floods. Pests and diseases that like warmer weather could also become a bigger problem for farmers.

Health and wellbeing

Climate change can also affect people's health. More hot days can lead to heat stress, especially for the elderly and young children. For many people, especially young people, thinking about the future of the planet can cause feelings of worry and anxiety. Experts say that taking positive action to help the environment is one of the best ways to cope with these feelings.

Indigenous peoples

Māori communities are especially vulnerable to climate change. Many marae, urupā, and other culturally important sites (wāhi tapu) are located on the coast. Rising sea levels and erosion are already threatening these special places. Climate change also affects traditional food sources from the land and sea.

What is New Zealand doing about climate change?

International agreements

New Zealand works with other countries to fight climate change. It signed the Paris Agreement in 2015. In this agreement, countries promised to work together to keep the global temperature rise well below 2 degrees Celsius.

Under the Paris Agreement, New Zealand set a goal to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. The country regularly reports on its progress and sets new targets to make sure it is doing its part.

The Zero Carbon Act

In 2019, the New Zealand government passed an important law called the Zero Carbon Act. The main goal of this law is for New Zealand to have 'net-zero' carbon emissions by the year 2050. This means the country will try to remove as much carbon dioxide from the air as it puts in.

The law also created a group of experts called the Climate Change Commission. Their job is to advise the government on the best ways to reach this goal and to check on the country's progress.

Planting trees

Trees are great at absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The government started a program with the goal of planting one billion trees. This project aims to help New Zealand become carbon neutral and also helps prevent soil erosion and improve water quality.

The political debate

New Zealand's political parties generally agree that climate change is a serious issue that needs to be addressed. However, they sometimes disagree on the best way to do it.

Some parties want to make very fast changes to reduce emissions, even if it costs more. Other parties want to make changes more slowly to protect jobs and the economy. This debate is about finding the right balance between protecting the environment and making sure life is still affordable for New Zealanders.

Society and activism

School strikes for climate

Many young people in New Zealand are passionate about fighting climate change. Inspired by the Swedish activist Greta Thunberg, thousands of students have taken part in school strikes. They march in the streets to ask the government to take stronger and faster action to protect the planet for their future. These protests show that young New Zealanders are very concerned and want to be part of the solution.

Declaring a climate emergency

Many city councils across New Zealand, including Auckland, Wellington, and Christchurch, have declared a "climate emergency." This is a way of saying that climate change is a very serious problem that needs urgent action.

In 2020, the New Zealand Parliament also officially declared a climate emergency. This sent a strong signal that the government sees climate change as one of the biggest challenges facing the country.

See also

- Agriculture in New Zealand

- Climate Change Commission

- Energy in New Zealand

- Environment of New Zealand

- Generation Zero

- Pollution in New Zealand