Commission for Relief in Belgium facts for kids

The Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB), also known as Belgian Relief, was a special group, mostly from America. It helped feed people in Belgium and northern France during World War I. These areas were taken over by Germany and didn't have enough food. A famous American, Herbert Hoover, who later became President of the United States, was the main leader of the CRB.

Contents

How the Idea to Help Started

When World War I began in 1914, Herbert Hoover was living in London. He was an engineer. Many American tourists were stuck in Europe and couldn't get home. Their money wasn't working, and ships weren't sailing. Hoover quickly set up a committee to help these Americans. He loaned them money and helped them find ways to travel. By October 1914, his group had helped about 120,000 Americans get home. This showed how good Hoover was at organizing things.

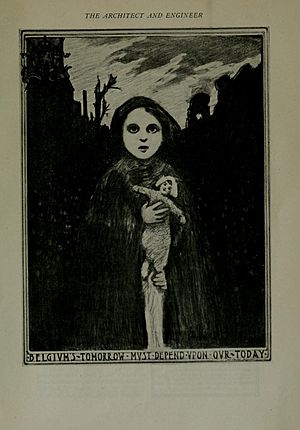

Soon after, Hoover was asked to help with an even bigger problem. In 1914, after Germany invaded Belgium, the country faced a huge food shortage. Belgium was a small country with many cities. It only grew enough food for about 20-25% of its people. The German soldiers were taking the food that was there to feed their own army. This meant the people of Belgium were in danger of starving.

It was hard to get food into Belgium because Great Britain had stopped all trade with Germany and the areas it controlled. This was called an economic blockade. The British worried that if food went into Belgium, the Germans would just take it. An American engineer named Millard Shaler tried to bring food in but faced this problem. He then contacted the American ambassador, Walter Hines Page, who reached out to Hoover for help.

How the Commission Worked

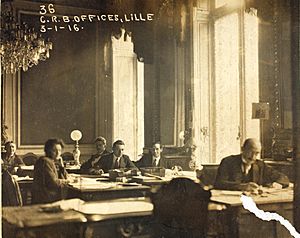

The CRB's job was to get food from other countries and ship it to Belgium. Once the food arrived, CRB workers watched over its distribution. A Belgian group called the Comité National de Secours et d'Alimentation (CNSA), led by Émile Francqui, helped give out the food.

It was important for CRB people to supervise. The Belgian CNSA workers lived under German rule and had to follow German orders. But the CRB workers, who were mostly American, did not. The food brought in by the CRB always belonged to the American ambassador, Brand Whitlock. It stayed his property until it was actually served on a plate. This helped make sure the food went to the people who needed it.

Challenges and Difficulties

The CRB faced problems from both sides of the war. The Germans didn't like having Americans in Belgium. They also blamed the British blockade for the food problems. Many important British leaders, like Lord Kitchener and Winston Churchill, thought Germany should feed the Belgians themselves. They felt that international help was making the war last longer by taking pressure off the Germans.

At different times, both sides tried to stop the relief efforts. German submarines were a constant danger, sinking relief ships, especially when tensions with the U.S. were high. For example, the ship Harpalyce was torpedoed by a German submarine in April 1915. It was returning after delivering food, and 15 people died.

Despite these challenges, the CRB was very successful. It bought and shipped about 5.7 million tons of food. This food went to 9.5 million people who were suffering because of the war. The committee arranged for ships to carry food to Belgian ports safely. This was agreed upon by both British and German leaders.

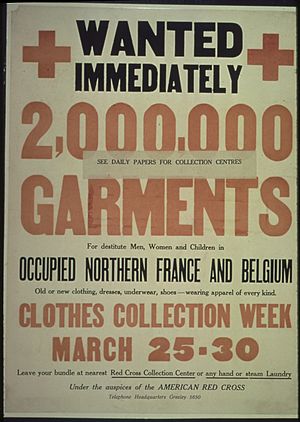

The Famous Flour Sacks

Between 1914 and 1919, the CRB worked completely with volunteers. They fed almost 10 million people in Belgium and northern France. They raised money, got food donations, shipped food past dangerous areas, and made sure it was given out fairly.

The CRB sent huge amounts of flour to Belgium. This flour came in cotton flour sacks from American mills. The CRB carefully watched these empty sacks. Cotton was valuable for making German ammunition. Also, the CRB worried that the sacks might be taken, filled with bad flour, and sold as real relief flour.

So, the empty flour sacks were carefully counted. They were then given to special schools, sewing workshops, convents, and artists. These places used the sacks to make new clothes, accessories, pillows, bags, and other useful items.

Many women embroidered over the mill logos and brand names on the sacks. But some created completely new designs. They would embroider, paint, or stencil these designs onto the fabric. Often, the sacks included messages of thanks to the Americans. They also featured lace, the Belgian and American flags, and symbols like the Belgian lion or American eagle. Artists even used the sacks as canvases for oil paintings.

The designs and messages on the sacks sometimes showed differences between the two main groups of people in Belgium: the Walloons (who spoke French) and the Flemish (who spoke Dutch).

The finished flour sacks were sold in Belgium, England, and the United States. The money raised helped buy more food and support prisoners of war. Many sacks were also given as gifts to CRB members as a thank you from the Belgian people.

Herbert Hoover received hundreds of these flour sacks as gifts. The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library-Museum now has one of the largest collections of World War I flour sacks in the world.

See also

- Belgium in World War I

- Belgian American Educational Foundation

- University Foundation

- Oswald Chew

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |