Olive-sided flycatcher facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Olive-sided flycatcher |

|

|---|---|

|

|

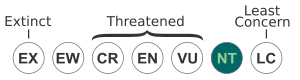

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Contopus

|

| Species: |

cooperi

|

|

|

The olive-sided flycatcher (Contopus cooperi) is a small to medium-sized bird in the Tyrant flycatcher family. It is a migratory bird, meaning it travels long distances. These birds fly from South America to North America to have their babies during the summer. They are great at flying and mostly eat insects they catch in the air. Since 2016, this bird has been considered 'near-threatened' globally by the IUCN. It is also listed as 'threatened' in Canada because its numbers are going down.

Contents

All About the Olive-Sided Flycatcher

How to Identify This Bird

Olive-sided flycatchers are small songbirds that migrate. They are smaller than a robin but bigger than a sparrow. You can spot them by their olive-grey or grey-brown feathers on top. They have a white chest and throat. The olive color on their back and wings is easiest to see in good light. The sides of their chest are grey, making them look like they are wearing a vest.

They have a fairly long beak and long wings for their size. Sometimes, they can raise some feathers on their head, making it look like they have a small crest. Male and female olive-sided flycatchers look alike. These birds often sit upright on top of dead branches or trees.

| Length | 7.1-7.9 inches (18-20 cm) |

| Weight | 1.0-1.4 ounces (28-40.4 grams) |

| Wingspan | 12.4-13.6 inches (31.5-34.5 cm) |

Birds That Look Similar

Olive-sided flycatchers can sometimes be confused with other birds in the Contopus group. These include the Greater Pewee, Western Wood-Pewee, Eastern Wood-Pewee, and the Eastern Phoebe.

Here's how to tell them apart:

- The greater pewee has a plain grey chest, not the vest-like look of the olive-sided flycatcher.

- Olive-sided flycatchers are twice as heavy as the western and eastern wood pewees.

- The eastern phoebe has more white on its belly than the olive-sided flycatcher.

Where They Live and Travel

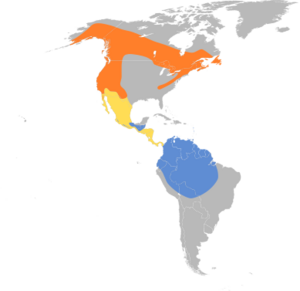

The olive-sided flycatcher lives across North and South America. They have different homes for breeding and for winter.

Their breeding areas stretch from California to New Mexico, all the way up to central Alaska. They also breed across Canada (but not most of the far north) and in parts of the northeastern US.

Their winter homes are mostly in the northern part of South America and a small area in Central America.

Their Favorite Places to Live

When they are breeding, these birds like open areas or the edges of boreal, coniferous forests (like pine or spruce trees), or temperate western forests. They often choose places up to 10,000 feet high, like in the Rocky Mountains. They always like to be near water. Sometimes, they even nest in cities or on farms.

In their winter homes, olive-sided flycatchers use similar places like open areas and forest edges. However, they don't need to be as close to water as they do when breeding. They also like habitats with very tall trees. Two types of forests they use in winter are tropical mountain and tropical lowland evergreen forests.

How They Behave

A study in Canada looked at how olive-sided flycatchers fly near their nests. It showed that some males would fly up to 49 meters away from their nest. They would only sing when they were more than 100 meters away. The study also found that pairs whose nests were in more open areas did not travel as far as those whose nests were deeper in the forest.

What Sounds Do They Make?

Bird vocalizations are the sounds birds make. Songbirds use songs to attract a mate and calls to talk to other birds.

- Song: During breeding season, male olive-sided flycatchers sing to find a mate. Their song sounds like they are saying "Quick, three beers!" It has three high-pitched sounds in a row. The first sound is shorter and not as loud as the other two. Sometimes, males might make growling sounds or squeaks if they are fighting with other males.

- Calls: Birds make calls to communicate with each other. This species' most common call is three quick "pip" sounds.

The amount a male sings changes during the breeding season. This seems to depend on whether he is single, has a mate, or is feeding young birds.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Olive-sided flycatchers usually have one group of babies per year. They lay about 3 to 4 eggs. The eggs hatch after 15 to 19 days. The baby birds stay in the nest for about the same amount of time.

The eggs are about 0.8-0.9 inches long and 0.6-0.7 inches wide. They are creamy white with brownish spots that form a ring on the wider end of the egg. The female chooses where to build the nest. Nests are usually on a horizontal branch of a conifer tree, but they can also be on other types of trees. The lowest nest found was 5 feet high, and the highest was 197 feet! In western areas, olive-sided flycatchers tend to build higher nests than in eastern areas.

The nest is cup-shaped, about 4.6 inches wide on the outside and 2.8 inches wide on the inside. The outside is made of twigs and small branches. The inside is lined with softer materials like grass, lichen, or pine needles. When the babies hatch, they are born naked and helpless. The male bird protects a large area around the nest. Both parents feed the young birds.

What Do They Eat?

Olive-sided flycatchers mostly eat by hawking. This means they catch flying insects in the air. They eat things like bees, wasps, moths, beetles, and grasshoppers. Sometimes, during migration or in winter, they will also eat fruit.

When they are taking care of their babies, olive-sided flycatchers have been seen eating their chicks' waste. Both parents do this for the first week after the babies hatch. After that, they start to remove the waste from the nest. Scientists think this behavior helps the parents get extra nutrients.

Their Long Migration Journey

Of all the flycatcher species that breed in the United States, the olive-sided flycatcher travels the farthest. Some of these birds fly up to 7,000 miles! They travel between central Alaska and Bolivia.

Status and Conservation

The IUCN Red List said in 2016 that the olive-sided flycatcher is a "near threatened" species. This means it's not in immediate danger, but it could become endangered or vulnerable soon. Canada also lists the olive-sided flycatcher as threatened because its population is shrinking.

There are about 1.9 million olive-sided flycatchers in the world. However, their numbers are going down by about 3% each year. In the last 50 years, their population has dropped by 79%.

How Climate Change Affects Them

Climate change is causing big changes in nature. A study in Nova Scotia looked for places where olive-sided flycatchers could survive well despite climate change. The study found that the height of the tree tops was very important for these birds because they need tall trees.

The results showed that good habitats for olive-sided flycatchers had taller tree tops. They also preferred areas with conifer forests and dead wood, which is important for finding food. These birds also seem to like valleys, lowlands, and flat areas that might have wetlands or streams. The study concluded that forests in Nova Scotia could be good places for olive-sided flycatcher populations to handle climate change.

What Threats Do They Face?

Research in Eastern Canada showed that human activities and roads negatively affect olive-sided flycatcher populations in national parks. This study showed how important protected areas are for this bird.

Losing their winter homes might be a main reason for their population decline. Even though they don't seem directly harmed by forest loss, they might be sensitive to it. The biggest threat is thought to be the decline in flying insect populations, likely due to insecticide use.

In their winter homes in the Andes mountains, their populations are highly threatened, but the exact reasons are not yet fully known. Forests that have been burned or recently logged can be good places for olive-sided flycatchers to find food because there are more flying insects. However, they could be harmed by methods used to stop wildfires or by salvage logging (cutting down trees after a fire). Collisions with communication towers also seem to be a cause of death for olive-sided flycatchers.