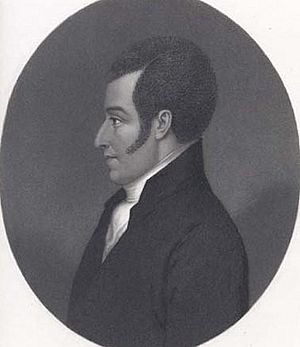

Daniel Coker facts for kids

Daniel Coker (1780–1846), originally named Isaac Wright, was an important African American leader. He was born into slavery in Maryland but later gained his freedom. He became a Methodist minister and spoke out against slavery. In 1816, he helped create the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME Church). This was the first independent church for Black people in the United States.

In 1820, Coker and his family moved to the British colony of Sierra Leone in Africa. He was the first Methodist missionary from a Western country there. Coker founded the West Africa Methodist Church. He and his family became important leaders among the Creole people in Sierra Leone.

Contents

Early Life and Freedom

Daniel Coker was born Isaac Wright in 1780. His mother, Susan Coker, was a white woman, and his father, Edward Wright, was an enslaved African American. Because his father was enslaved, Isaac was also considered a slave under the laws at the time.

Isaac grew up in Maryland. He even went to primary school with his white half-brothers. He served as their helper, and one of his half-brothers supposedly wouldn't go to school without him.

As a teenager, Isaac ran away to New York. There, he changed his name to Daniel Coker and joined the Methodist Episcopal Church. He received permission to preach from Francis Asbury, a British missionary.

Coker later returned to Baltimore. Friends helped him buy his freedom from his master. This made his legal status secure. As a free Black person, he could teach at a local school for Black children. Baltimore had many free Black people at this time, especially after the Revolutionary War.

A Leader in the Church

In 1802, Daniel Coker became a deacon in the Methodist Episcopal Church. He strongly opposed slavery and wrote pamphlets to protest it. In 1810, he published a pamphlet called Dialogue between a Virginian and an African minister. This writing was known for its quality and was one of the few protest pamphlets published in the Southern states where slavery was common.

While working at Sharp Street Church, Coker felt that Black Methodists should have their own church. He started the African Bethel Church, which later became known as Bethel A.M.E. Church.

In 1807, Coker also founded the Bethel Charity School for Black children. One of his students was William J. Watkins, who later became a strong opponent of slavery.

In 1816, Coker went to Philadelphia. He worked with Richard Allen to organize the national African Methodist Episcopal Church. Several churches, mostly from the mid-Atlantic area, joined together to form this first independent Black church in the United States. Coker was chosen to be the first bishop, but he let Richard Allen take the role instead. Allen had founded the first AME Church in Philadelphia, called Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church.

After returning to Baltimore, Coker faced some challenges. In 1818, church leaders removed him for a short time. He was allowed back the next year but could only preach with a local minister's approval. Even though he kept teaching, it was hard to support his family. In 1820, he decided to move with his family to Africa as a missionary. He traveled with the help of the American Colonization Society.

Journey to Western Africa

In early 1820, Daniel Coker sailed to Africa on a ship called the Elizabeth. He was one of 86 African Americans helped by the American Colonization Society (ACS). This group wanted to help free Black Americans move to West Africa. Some people believed free Black people faced too much unfairness in the United States. Others thought free Black people might cause problems for slave societies in the South.

The people on the Elizabeth were the first African-American settlers in what is now Liberia. Their descendants became known as the Krio people.

Coker was one of four AME missionaries on the ship. During the journey, he started the first international branch of the AME Church.

The ACS planned to start a colony at Sherbro Island, which is now part of Sierra Leone. This area was a British colony at the time. The new settlers were not used to the local diseases. The area was swampy, with many mosquitoes that carried illnesses. Most of the white colonists and one-third of the African Americans died. This included three of the four missionaries. Just before he died, the expedition's leader asked Coker to take charge. Coker helped the remaining settlers through their sadness and helped them survive.

Coker led the group to find a new place on the mainland. He and his family settled in Hastings, Sierra Leone. This was a new village about 15 miles from the first settlement of Freetown. Hastings was for Liberated Africans. These were people freed by the British Navy from illegal slave ships, as the transatlantic slave trade had been banned. Hastings was one of several new villages started by the Church Missionary Society. Coker became the head of an important Creole family, the Cokers. Daniel Coker Jr., his son, became a leader in Freetown. Coker's family members still live in Freetown and are well-known Creole families. Other members of the expedition settled in what became Liberia.

In 1891, Henry McNeal Turner, another A.M.E. Church bishop, spoke about Coker's achievements. He wrote that Coker played a big part in the early settlement of Liberia. He also said that Coker played a huge role among the early settlers of Sierra Leone, and that his children and grandchildren were still there.

See also

- Liberia

- Sierra Leone

- Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church

- Sharp Street Memorial United Methodist Church and Community House

- Paul Cuffe

- Henry McNeal Turner

- David Brion Davis

- Lott Cary

Images for kids