Dziga Vertov facts for kids

Dziga Vertov (born David Abelevich Kaufman, and also known as Denis Kaufman; 2 January 1896 – 12 February 1954) was a Soviet pioneer in making documentary films and newsreels. He was also a film thinker. His ideas and ways of making movies greatly influenced a style of documentary filmmaking called cinéma vérité. This style focuses on showing real life as it happens.

Vertov's famous film Man with a Movie Camera (1929) was voted one of the greatest films ever made by critics in a 2012 poll. His younger brothers, Boris Kaufman and Mikhail Kaufman, were also well-known filmmakers. His wife, Yelizaveta Svilova, was also a filmmaker.

Contents

Dziga Vertov: A Film Pioneer

Early Life and Dreams

Vertov was born David Abelevich Kaufman into a Jewish family in Białystok, which was then part of the Russian Empire. His family moved to Moscow in 1915 to escape the German Army. They later settled in Petrograd, where Vertov started writing poetry and science fiction.

From 1916 to 1917, Vertov studied medicine. In his free time, he experimented with "sound collages," which are like mixing different sounds together. He later chose the name "Dziga Vertov," which means 'spinning top' in Ukrainian.

Making Movies: Newsreels and New Ideas

After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, when he was 22, Vertov started editing for Kino-Nedelya. This was Russia's first weekly newsreel series. While working there, he met Yelizaveta Svilova, who would become his wife and a close filmmaking partner. She worked with him as an editor and later as a co-director on films like Man with a Movie Camera.

Vertov worked on Kino-Nedelya for three years. He helped set up a special film-car on a "propaganda train" during the Russian Civil War. These trains traveled to battlefronts to boost the spirits of soldiers and encourage revolutionary ideas. Vertov's car had equipment to film, develop, edit, and show movies.

In 1922, Vertov, his wife Elizaveta Svilova, and his brother Mikhail Kaufman formed a group called the "Council of Three." They wrote articles about their ideas on filmmaking. Vertov was very interested in how machines worked, and this led him to think about how cameras could show the world in new ways.

What is "Kino-Pravda"?

In 1922, Vertov started a film series called Kino-Pravda, which means "film truth." His main goal was to capture "film truth"—to show parts of real life that, when put together, reveal a deeper truth that people might not see with their own eyes.

In Kino-Pravda, Vertov filmed everyday life. He showed marketplaces, schools, and people going about their day. Sometimes he used a hidden camera. He usually avoided acting or staged scenes. The films were simple and focused on showing things as they were.

Twenty-three issues of Kino-Pravda were made over three years. Each one was about twenty minutes long and usually covered three topics. For example, one film showed how a trolley system was being fixed, and another showed farmers joining together in groups. Vertov wanted his audience to think actively about what they saw.

Vertov believed that traditional stories in movies were like "an opiate for the masses." He wanted to break away from films that told fictional stories. He felt that movies should show real life and help people understand the world better.

The Man with a Movie Camera

In 1929, Vertov made one of his most famous films, Man with a Movie Camera. He said he was trying to "clean up film-language" and make it completely different from theater or books. This film was made in Ukraine.

Some people thought that certain scenes in the film were staged, which seemed to go against Vertov's idea of "life as it is." However, Vertov had two ideas: "life as it is" meant recording life without the camera changing it. "Life caught unawares" meant recording life when it was surprised by the camera.

Vertov used many special camera techniques in this film, like slow motion and fast motion. His brother Mikhail Kaufman explained that these techniques were used to break down and understand images. For example, in the film, two trains appear to almost melt into each other. Vertov wanted to show how two passing trains actually look to the eye, even if it seems unusual.

The film was also meant to help people in the Soviet Union become more efficient. Vertov wanted to show a peaceful connection between human actions and machine actions, almost as if they were one.

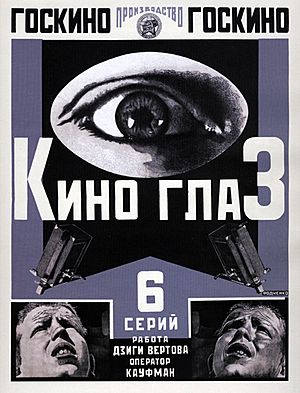

The "Cine-Eye" Idea

Vertov developed a filmmaking idea called "Cine-Eye" (Kino-Glaz). He believed that the "Cine-Eye" would help people become better and more precise, like machines. He said, "I am the Cine-Eye. I am the mechanical eye. I the machine show you the world as only I can see it. I emancipate myself henceforth and forever from human immobility. I am in constant motion... My path leads towards the creation of a fresh perception of the world. I can thus decipher a world that you do not know."

Vertov thought that films were too "romantic" and "theatrical" because they were influenced by books, plays, and music. He wanted to move away from these "fictional" ways of making movies. He wanted films to be based on the rhythm of machines and to bring people closer to machines.

He surrounded himself with other filmmakers who believed in his ideas. These were the Kinoks, who helped him try to make "Cine-Eye" a success. In May 1927, Vertov moved to Ukraine, and the Cine-Eye movement changed.

Later Films and Legacy

Vertov continued making successful films into the 1930s. Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass (1931) looked at Soviet miners. It was called a 'sound film' because it used sounds recorded on location, woven together like a symphony.

Three years later, Three Songs About Lenin (1934) showed the Russian Revolution through the eyes of farmers. This film was released in the Soviet Union in November 1934. Later, a new version was made in 1938 to include more about Joseph Stalin's achievements.

After 1934, Vertov had to change his filmmaking style to fit the official art style of the Soviet Union, called socialist realism. He ended up mostly editing newsreels. Lullaby, released in 1937, was one of his last films where he could fully express his artistic vision.

Dziga Vertov passed away from cancer in Moscow in 1954.

Family Connections

Vertov's brother Boris Kaufman was a cinematographer who worked on famous films like L'Atalante (1934) and later won an Oscar for his work on On the Waterfront. His other brother, Mikhail Kaufman, also worked with Vertov before becoming a documentary director himself. Mikhail Kaufman's first film as a director was In Spring (1929).

In 1923, Vertov married his long-time filmmaking partner, Elizaveta Svilova.

Influence and Legacy

Vertov's ideas are still important today. His work influenced the cinéma vérité movement of the 1960s, which was named after his Kino-Pravda series. Many filmmakers and directors, like Jean Rouch, were inspired by Vertov's theories. Rouch even used Vertov's ideas when making Chronicle of a Summer.

Movements like the Free Cinema in the United Kingdom, Direct Cinema in North America, and the Candid Eye series in Canada all owe a lot to Vertov's pioneering work.

In the 1960s and 1970s, there was a new interest in Vertov's films and ideas around the world, including in the Soviet Union. His reputation was restored, and books were written about him. In 1984, the first American showing of Vertov's films took place in New York.

Some modern thinkers, like Lev Manovich, see Vertov as one of the early pioneers of "database cinema," which is a way of making films using many different pieces of information.

Films by Dziga Vertov

- 1918 Kino Nedelya (Cinema Week)

- 1918 Anniversary of the Revolution

- 1921 History of the Civil War

- 1922 Kino-Pravda

- 1924 Soviet Toys

- 1924 Kino-Eye

- 1926 A Sixth Part of the World

- 1928 The Eleventh Year

- 1929 Man with a Movie Camera

- 1931 Enthusiasm

- 1934 Three Songs About Lenin

- 1937 In Memory of Sergo Ordzhonikidze

- 1937 Lullaby

- 1938 Three Heroines

- 1942 Kazakhstan for the Front!

- 1944 In the Mountains of Ala-Tau

- 1954 News of the Day

Lost Films

Some of Vertov's early films were lost for many years. For example, only a small part of his 1918 film Anniversary of the Revolution was known. In 2018, a Russian film historian found the lost parts and put the film back together. In 2022, he also reconstructed another lost film, The History of the Civil War (1921), using old materials.

See also

In Spanish: Dziga Vértov para niños

In Spanish: Dziga Vértov para niños

- Soviet montage theory

- Cinéma vérité

- Pure cinema

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |