Edith Pechey facts for kids

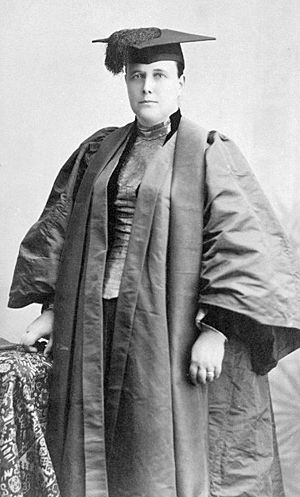

Mary Edith Pechey (born October 7, 1845 – died April 14, 1908) was a very important woman in British history. She was one of the first women doctors in the United Kingdom. She also fought for women's rights, like the right to vote.

Edith spent over 20 years working in India as a top doctor at a hospital for women. She also helped with many other social causes there.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Edith Pechey was born in Langham, Essex, England. Her mother, Sarah, was a lawyer's daughter who had studied Greek. This was very unusual for women back then. Her father, William, was a Baptist minister with a degree in theology.

Edith was taught at home by her parents. They both loved learning very much. Before she decided to study medicine, she worked as a governess and a teacher.

The Fight to Study Medicine

In 1869, a woman named Sophia Jex-Blake wanted to study medicine at the University of Edinburgh. When her application was turned down, she asked other women to join her. Edith Pechey was one of the first to reply.

Edith worried if she was smart enough. But she wrote that she had "moderate abilities and a good share of perseverance." She also had "a real love of the subjects of study."

Edith became one of the Edinburgh Seven. This was a group of seven brave women who were the first female medical students at any British university. The other women were Mary Anderson, Emily Bovell, Matilda Chaplin, Helen Evans, Sophia Jex-Blake and Isabel Thorne.

Edith quickly showed how smart she was. In her first year, she got the best grade in the chemistry exam. This meant she should have won a special award called the Hope Scholarship.

The Hope Scholarship Problem

The Hope Scholarships were awards given to the top four students in chemistry. These students got to use the university lab for free. Edith Pechey came in first place, so she should have received the scholarship.

However, the chemistry professor, Dr Crum Brown, was worried. Male students were becoming angry because the women were doing so well. Many professors also didn't like having women in the university.

So, Dr. Crum Brown decided not to give the scholarship to Edith. He gave it to male students who had lower grades. He said it was because women were taught in separate classes.

Appealing for Fairness

Because women were in separate classes, Dr. Crum Brown also refused to give them the usual certificates for their chemistry lessons. He gave them special "ladies' class" certificates instead. These were not accepted for a medical degree. Sophia Jex-Blake called them "Strawberry Jam Labels" because they were useless.

The women complained to the university's main committee, the Senatus Academicus. Edith Pechey demanded her scholarship. The other women asked for the proper chemistry certificates.

On April 9, 1870, the committee met. After much discussion, they agreed to give the women the correct certificates. But they still refused to give Edith the Hope Scholarship.

National Attention for the Edinburgh Campaign

The story of the Hope Scholarship became very famous. Newspapers across the UK wrote about the problems these women faced while studying medicine in Edinburgh. Most of the articles supported the women.

The Times newspaper praised Miss Pechey. They said she showed women's intelligence and handled her disappointment with grace.

The Spectator newspaper made fun of the university. They pointed out how unfair it was to make women attend separate, more expensive classes, and then use that as an excuse to deny them awards.

Becoming a Doctor

In 1873, the women had to stop their fight to graduate from Edinburgh. Edith Pechey then wrote to the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland. She asked to take exams to become a licensed midwife.

She worked at a hospital in Birmingham for a while. Even without an official degree, her good grades and recommendations helped her get the job. Next, she went to the University of Bern in Switzerland. She passed her medical exams in German in 1877 and earned her medical degree.

Soon after, the Irish College started allowing women doctors. Edith passed their exams in Dublin in May 1877. She was finally a qualified doctor!

For the next six years, Edith practiced medicine in Leeds, England. She taught women about health and gave lectures on medical topics. She was even asked to give the first speech when the London School of Medicine for Women opened.

In 1883, an American businessman named George A. Kittredge was looking for women doctors to work in India. He wanted to help Indian women, who often could not see male doctors. Edith was suggested for a job at a new hospital in Bombay (now Mumbai).

Working in India

Edith arrived in Bombay on December 12, 1883. She quickly learned Hindi. Besides working at the Cama Hospital, she also managed another clinic for women. After a few years, she started a successful training program for nurses at Cama.

Edith worked hard to fight against unfair ideas about women. She argued for equal pay and chances for female medical workers. She also campaigned for bigger social changes, like ending child marriage. She often gave talks about education for women.

Many important groups invited her to be their first woman member. These included the University of Bombay and the Royal Asiatic Society.

In March 1889, she married Herbert Musgrave Phipson. He was a reformer and also helped with the "medical women for India" fund. After marriage, she used the name Pechey-Phipson.

Five years later, due to her health, she stopped working at the hospital. But she continued to see private patients. In 1896, when bubonic plague hit Bombay, she helped with public health efforts. Her ideas helped manage a later cholera outbreak. She also helped Rukhmabai, who became one of the first Indian women doctors.

Later Years

Edith Pechey-Phipson and her husband returned to England in 1905. She quickly became involved in the suffrage movement. This movement fought for women's right to vote. She represented suffragists from Leeds at a big meeting in Denmark in 1906.

She was also part of the "Mud March" protest in 1907. This was a large demonstration organized by the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. However, she was becoming ill and needed treatment for breast cancer.

Edith died from her illness on April 14, 1908, at her home in Folkestone, Kent. Her husband set up a scholarship in her name at the London School of Medicine for Women. In India, a sanatorium (a type of hospital) for women and children in Nasik was named after her until 1964.

Recognition

The Edinburgh Seven, including Edith Pechey, were given special honorary medical degrees by the University of Edinburgh on July 6, 2019. Current medical students accepted the degrees for them. This event was part of the university's efforts to remember the achievements of these pioneering women.

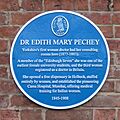

In July 2021, a special Blue Plaque was put up at 8, Park Square, Leeds. This is where Edith Pechey had her medical practice.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Edith Pechey para niños

In Spanish: Edith Pechey para niños