Edwin Smith Papyrus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Edwin Smith Papyrus |

|

|---|---|

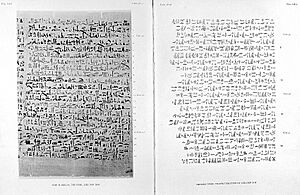

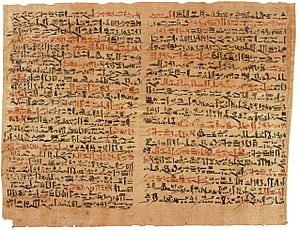

Plates vi & vii of the Edwin Smith Papyrus at the Rare Book Room, New York Academy of Medicine

|

|

| Size | length: 4.68 meters |

| Created | c. 1600 BC |

| Discovered | Egypt |

| Present location | New York City, New York, United States |

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is a very old medical book from ancient Egypt. It's named after Edwin Smith, who bought it in 1862. This papyrus is the oldest known book about injuries and surgery.

This amazing document might have been a guide for military doctors. It describes 48 different cases of injuries, like broken bones, wounds, and dislocations. It was written around 1600 BCE, during a time in ancient Egypt called the Second Intermediate Period.

What makes this papyrus special is its scientific approach. Other ancient Egyptian medical texts, like the Ebers Papyrus, often mixed medicine with magic. But the Edwin Smith Papyrus focuses on practical and logical ways to treat injuries. It shows that ancient Egyptians had a very smart way of thinking about medicine.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is a scroll about 4.68 meters (or 15.3 feet) long. The front side, called the recto, has 377 lines of text. The back side, called the verso, has 92 lines. It's written from right to left in hieratic, which is a cursive (flowing) form of Egyptian hieroglyphs. The main text is in black ink, and important explanations are in red ink.

Most of the papyrus talks about injuries and surgery. The recto side describes 48 different injury cases. Each case explains the injury, how to examine the patient, what the diagnosis and outlook are, and how to treat it. The verso side has eight magic spells and five medical recipes. These spells were probably used only when a patient was very sick and other treatments didn't work.

Contents

Who Wrote the Papyrus?

It's not clear who wrote the Edwin Smith Papyrus. Most of it was written by one scribe, with a few small parts added by another. The papyrus ends suddenly, without saying who the author was.

Many experts believe it's an unfinished copy of an even older book from the Old Kingdom of Egypt (around 3000–2500 BCE). This is because the language and style seem very old. One scholar, James Henry Breasted, wondered if the original author might have been Imhotep. Imhotep was a famous architect, priest, and doctor from the Old Kingdom. But this is just a guess, as there's no real proof.

How Doctors Used It

The papyrus shows a very logical and practical way of treating patients. It describes 48 different injury cases, organized by body part. It starts with head injuries, then moves down to the neck, arms, and torso. This is similar to how modern anatomy books are organized!

Each case has a clear title, like "Practices for a gaping wound in his head, which has penetrated to the bone and split the skull." Doctors would examine the patient carefully. They would look, smell, and feel the injury, and even check the patient's pulse.

After the examination, the doctor would make a diagnosis and give a prognosis (what they thought would happen). They would choose one of three statements:

- "An ailment which I will treat" (meaning they could help)

- "An ailment with which I will contend" (meaning it would be a challenge)

- "An ailment not to be treated" (meaning they couldn't do anything)

Finally, the papyrus suggests different treatments.

Treatments included closing wounds with stitches (for lips, throat, and shoulders), using bandages, splints, and poultices (soft, moist packs). They also used honey to prevent and treat infections, and raw meat to stop bleeding. For head and spinal injuries, keeping the patient still was advised.

The papyrus also contains amazing details about the human body. It has the first known descriptions of parts of the brain, the fluid around the brain, and how the brain pulsates. The medical knowledge in this papyrus was very advanced, even more so than what Hippocrates (a famous Greek doctor) knew 1000 years later!

It even recognized that brain injuries could cause paralysis in other parts of the body. It also noted that crushing injuries to the spine could affect movement and feeling. Because of its practical nature and focus on injuries, many believe this papyrus was a textbook for treating wounds from battles.

History of the Papyrus

The Edwin Smith Papyrus was written between the 16th and 17th Dynasties of ancient Egypt. It likely came from the city of Thebes, which was the capital at that time.

Edwin Smith, an American expert on ancient Egypt, bought the papyrus in 1862. He got it from an Egyptian dealer in Luxor, Egypt.

After Smith's death, his daughter gave the papyrus to the New York Historical Society. In 1920, a scholar named Caroline Ransom Williams realized how important it was. She contacted James Henry Breasted, who was a famous Egyptologist.

Breasted, with help from Dr. Arno B. Luckhardt, finished the first full translation of the papyrus in 1930. This translation completely changed how people understood the history of medicine. It showed that ancient Egyptian doctors used scientific methods, not just magic. They relied on careful observation and examination.

From 1938 to 1948, the papyrus was at the Brooklyn Museum. In 1948, it was given to the New York Academy of Medicine, where it is kept today.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus was displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from 2005 to 2006. During this time, James P. Allen, an expert on Egyptian art, published a new translation. This was the first complete English translation since Breasted's in 1930. It helped people understand the ancient text and medicine even better.

What Injuries Are Listed?

The papyrus lists cases in order, starting from the head and moving down the body:

- Head (27 cases, the first one is incomplete)

- Skull, soft tissue, and brain: Cases 1-10.

- Nose: Cases 11-14.

- Upper jaw area: Cases 15-17.

- Side of the head (temple area): Cases 18-22.

- Ears, lower jaw, lips, and chin: Cases 23-27.

- Throat and Neck (Cervical Vertebrae): Cases 28-33.

- Collarbone (Clavicle): Cases 34-35.

- Upper Arm Bone (Humerus): Cases 36-38.

- Breastbone, overlying soft tissue, and true ribs: Cases 39-46.

- Shoulders: Case 47.

- Spinal Column: Case 48 (incomplete).

See also

- List of ancient Egyptian papyri

- Ancient Egyptian medicine

- Medical literature

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |