Elisabeth Kübler-Ross facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Elisabeth Kübler

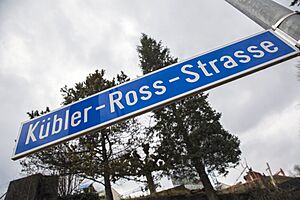

July 8, 1926 Zürich, Switzerland

|

| Died | August 24, 2004 (aged 78) Scottsdale, Arizona, U.S.

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | University of Zürich (MD) |

| Known for | Kübler-Ross model |

| Spouse(s) |

Emanuel Ross

(m. 1958; div. 1979) |

| Children | Ken Ross Barbara Ross |

| Awards | National Women's Hall of Fame, Time "Top Thinkers of the 20th Century", Woman of the Year 1977, New York Public Library's: Book of the Century, 20 Honorary degrees |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychiatry, hospice, palliative care, bioethics, grief, author |

| Institutions | University of Chicago |

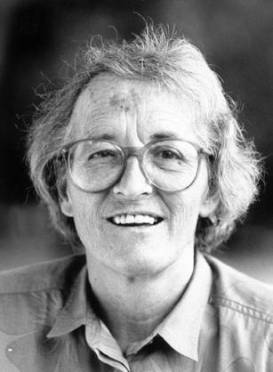

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (July 8, 1926 – August 24, 2004) was a Swiss-American psychiatrist. She was a leader in studying near-death experiences. She also wrote the famous book On Death and Dying (1969). In this book, she first shared her idea of the five stages of grief. This idea is also known as the "Kübler-Ross model".

In 1970, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross gave an important speech at Harvard University. It was about her book "On Death and Dying." By 1982, she had taught 125,000 students about death and dying. She taught in colleges, hospitals, and medical schools. In 1999, her book was named one of the "Books of the Century" by the New York Public Library. Time magazine called her one of the "100 Most Important Thinkers" of the 20th century. She received over 100 awards and twenty honorary degrees. In 2007, she joined the National Women's Hall of Fame. Her writings are kept at Stanford University's Green Library.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Early Life and Education

Elisabeth Kübler was born on July 8, 1926, in Zürich, Switzerland. She grew up in a Christian family. She was one of three triplets, and two of them were identical. Elisabeth was born very small, weighing only 2 pounds. She said her mother's love helped her survive.

At age 5, Elisabeth got pneumonia and went to the hospital. Her roommate there died peacefully. This was Elisabeth's first experience with death. These early events made her believe that death is a natural part of life. She felt people should face it with dignity and peace.

During World War II, when she was only 13, Elisabeth worked in a lab for refugees in Zürich. From a young age, she wanted to be a doctor. Her father wanted her to be a secretary for his business. But she refused and left home at 16. She worked as a housemaid and met a doctor who helped her. Then, she became an apprentice for a scientist named Dr. Braun. She remembered getting her first lab coat with her name on it.

On May 8, 1945, at age 18, she joined the International Voluntary Service. This group worked for peace. Two days later, she left Switzerland for the first time. Her first job was to help rebuild a French town called Ecurcey. For the next four years, she did relief work in many European countries.

In 1947, she visited the Majdanek concentration camp in Poland. This visit deeply changed how she saw kindness and human strength. The sad stories of survivors left a lasting mark on her. They inspired her to help and heal others. She was especially touched by drawings of hundreds of butterflies on the walls of the children's barracks. These drawings were made by children facing death. They stayed with Kübler-Ross for years. They greatly shaped her ideas about caring for people at the end of their lives.

Later in 1947, she lived briefly with Romany people near the Polish/Russian border. She had to leave quickly because the borders were closing. Luckily, she met U.S. officers who helped her fly from Poland to Berlin.

After returning to Zürich, she worked for a dermatologist. Then, she worked many jobs to support herself. She gained hospital experience while helping refugees. After this, she studied medicine at the University of Zurich. She graduated in 1957.

Career Highlights

Starting Her Medical Work

After graduating in 1957, Kübler-Ross moved to New York in 1958. She wanted to work and study more.

She started her psychiatry training at the Manhattan Psychiatric Center in 1959. She began creating her own treatments. These were for patients with schizophrenia and those called "hopeless patients." This term was used for people who were terminally ill. Her programs aimed to give patients back their dignity and self-respect. Kübler-Ross also tried to reduce the strong medications that made patients too sleepy. She found ways to help them connect with the outside world.

She was shocked by how badly psychiatric patients were treated. Dying patients were often ignored by hospital staff. This made her want to make a difference. She created a program that focused on individual care for each patient. This program worked very well. It led to big improvements in the mental health of 94% of her patients.

In 1962, she started working at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. There, Kübler-Ross was a junior teacher. She gave her first interview with a young terminally ill woman. She did this in front of many medical students. She wanted to show a human being who wanted to be understood. She wanted to show how the illness affected her life. She told her students:

Now you are reacting like human beings instead of scientists. Maybe now you'll not only know how a dying patient feels but you will also be able to treat them with compassion – the same compassion that you would want for yourself

Kübler-Ross finished her psychiatry training in 1963. She moved to Chicago in 1965. She sometimes questioned the usual ways of psychiatry. She also had 39 months of psychoanalysis training in Chicago. She became a teacher at the University of Chicago's Pritzker School of Medicine. There, she started weekly seminars. These included live interviews with terminally ill patients. Her students took part, even though many medical staff resisted.

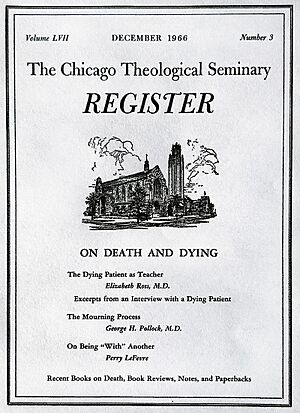

By 1966, Kübler-Ross gave regular weekly talks about dying patients. In late 1966, she wrote an article called "The Dying Patient as Teacher." It was for The Chicago Theological Seminary Journal. She worried about her English, but the editor told her it was fine. A copy of her article reached an editor at Macmillan Publishing Company. On July 7, 1967, Macmillan offered her a contract. They wanted her to turn her work into a book. The book was called "On Death & Dying." It was published in November 1969. It quickly became a best-seller. This changed Elisabeth's life greatly.

In November 1969, Life magazine wrote an article about Kübler-Ross. This made her work known to the public. The response was huge. It made Kübler-Ross decide to focus her career on helping the terminally ill and their families. She stopped teaching at the university. She chose to work privately on what she called "the greatest mystery in science"—death.

During the 1970s, Kübler-Ross became a leader in the worldwide hospice movement. She traveled to over twenty countries. She started many hospice and palliative care programs. In 1970, she spoke at the important Ingersoll Lecture at Harvard University. Her topic was death and dying. In 1972, she spoke to the United States Senate Special Committee on Aging. She promoted the "Death With Dignity" movement. In 1977, Ladies' Home Journal named her "Woman of the Year." In 1978, Kübler-Ross helped start the American Holistic Medical Association.

Healing Center in California

Kübler-Ross was a key person in the hospice care movement.

In 1977, she started "Shanti Nilaya" (Home of Peace) in California. It was on forty acres of land. Here, Kübler-Ross held "Life, Death, and Transition (LTD) workshops." These workshops helped people deal with "unfinished business" in their lives. She also wanted it to be a healing center for dying people and their families.

In the late 1970s, she became interested in out-of-body experiences. She also explored ways to try to contact the dead. This led to a problem with the Shanti Nilaya Healing Center. She was tricked by someone named Jay Barham. She announced that she was ending her connection with Jay Barham and his wife in June 1981.

Research on Near-Death Experiences

Kübler-Ross also studied near-death experiences (NDEs). She supported spiritual guides and the idea of an afterlife. She was on the board of the International Association for Near-Death Studies (IANDS).

Kübler-Ross first wrote about her interviews with dying patients in her book On Death and Dying: What the Dying Have to Teach Doctors, Nurses, Clergy, and Their Own Families (1969). This book originally had a chapter on NDEs. But her colleagues told her to remove it. They thought it would make the public less accepting of the book. So, she took it out before the book was printed.

Kübler-Ross later wrote several books about NDEs. Her book On Life After Death (1991) was made from three of her speeches. The English version sold over 200,000 copies. The German version also sold hundreds of thousands of copies.

Another book, The Tunnel and The Light (1999), was also made from her past speeches.

Her Work with Children

Kübler-Ross worked a lot with children. She wrote three books about how children understand death. These books were The Dougy Letter (1979), Living with Death and Dying (1981), and On Children and Dying (1983).

She wrote Living with Death and Dying because many people asked for more details. They wanted to know how terminally ill children express their needs. She said that children understand death more than we think. They talk about it more easily than we assume. The way children talk about death is special, depending on their age.

Young children often use "Nonverbal Symbolic Language." This means they use drawings, pictures, or objects to show what they understand about death. They might not know the words to use. Older children and teens use "Verbal Symbolic Language." They use detailed stories and strange questions to share their feelings about death. Children might be afraid to ask direct questions about their own death. So, they might make up stories or odd questions to get their needs met.

AIDS Work

During a time when people with AIDS were often rejected, Kübler-Ross welcomed them. She held many workshops around the world. These workshops were about life, death, grief, and AIDS. She taught about the disease and worked to reduce the unfair treatment connected to it.

In December 1983, she moved her home and workshop center to her farm in Head Waters, Virginia. This helped her travel less. Later, she created a workshop just for patients with AIDS. Most people with AIDS at that time were gay men. But women and children also got the disease. She was surprised by how many children and babies had AIDS. She noted that babies usually got the disease from their mother or father, or from infected blood transfusions.

During this time, Kübler-Ross became interested in hospice care in prisons. In the mid-1980s, a prison in Vacaville, California, became a main place for healthcare for prisoners. In 1984, Kübler-Ross sent one of her staff members to check on conditions there. Later, she asked Nancy Jaicks Alexander to help improve end-of-life care for AIDS patients in the Vacaville prison. Nancy and her husband started the first prison hospice in 1992. Kübler-Ross also worked on prison projects in Hawaii, Ireland, and Scotland. In June 1991, she held her first workshop inside a prison in Edinburgh, Scotland.

One of her biggest wishes was to build a hospice for abandoned babies and children with HIV. She wanted to give them a loving home until they died. Kübler-Ross tried to set this up in the late 1980s in Virginia. But local residents feared infection. They stopped the necessary zoning changes. In October 1994, she lost her house and many belongings in a fire. It is thought that people who opposed her AIDS work started the fire.

Lasting Impact

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross changed how the world viewed terminally ill people. She was a pioneer in hospice care, palliative care, and bioethics. She also led research into near-death experiences. She was the first to bring the lives of dying people to public attention. Kübler-Ross pushed for doctors and nurses to "treat the dying with dignity."

Balfour Mount, the first palliative care doctor in Canada, said Kübler-Ross inspired his interest in end-of-life care. Kübler-Ross wrote over 20 books about death and dying. These books have been translated into 44 languages. Near the end of her life, she co-wrote two books with David Kessler. One was On Grief and Grieving (2005). In 2018, Stanford University got Kübler-Ross's writings from her family. They are building a digital library of her papers and interviews.

After working with many dying patients, Kübler-Ross published On Death and Dying in 1969. In this book, she introduced her famous "five stages" model. These stages are denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. This model is now widely accepted. In her book, Kübler-Ross also mentioned other feelings. These include shock, partial denial, hope, and sadness.

Some experts have criticized the five-stage model. They argue that it should not be applied to everyone in grief. They also say that grief does not always happen in a set order. Kübler-Ross herself, with David Kessler, warned that the stages "are not stops on some linear timeline in grief. Not everyone goes through all of them or in a prescribed order."

In the 1980s, more companies started using the five stages model. They used it to explain how people react to change and loss. This is now known as the "Kübler-Ross Change Curve." Many large companies use it today.

The Elisabeth Kübler-Ross Foundation continues her work. It has chapters around the world. She received many awards and honors. These include honorary degrees from different universities. She is also featured in a photo exhibit at the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. In 2019, American Journal of Bioethics dedicated an entire issue to her book On Death and Dying. For example, bioethicist Mark G. Kuczewski wrote that Kübler-Ross helped create modern bioethics. She showed the importance of listening to patients to understand their needs.

Personal Life

In 1958, Elisabeth married Emanuel "Manny" Ross. He was an American medical student. They moved to the United States. They both did their internships at Glen Cove Community Hospital in New York. They had their first child, a son named Kenneth, in 1960. Their daughter, Barbara, was born in 1963. Their marriage ended in 1979. Elisabeth and Emanuel remained friends until he died in 1992.

Final Years and Death

Kübler-Ross had several strokes between 1987 and 1994. None of them caused lasting physical problems. After a house fire in Virginia in 1994, she moved to Scottsdale, Arizona. Her healing center in Virginia closed. The next month, she bought a home in Arizona. After a bigger stroke in May 1995, she used a wheelchair. She wished she could choose her time of death.

In 1997, Oprah Winfrey interviewed Kübler-Ross in Arizona. They talked about whether Kübler-Ross herself was going through the five stages of grief. In July 2001, she traveled to Switzerland. She celebrated her 75th birthday with her triplet sisters. After the events of September 11, Time magazine brought her to New York City. They wanted her to talk about the city's grief. In a 2002 interview, she said she was ready for death. She even welcomed it.

From 2002 until August 2004, she lived in a nursing home. She received hospice care there. Kübler-Ross died in Scottsdale on August 24, 2004, at age 78. Her two children were with her. She died of natural causes. She was buried at Paradise Memorial Gardens Cemetery in Scottsdale.

After Elisabeth died, Muhammad Ali shared his thoughts. He said, "Elisabeth taught us that self-realization is an important part of understanding the meaning of life… It is not coincidence… that the woman who taught us so much about death and dying as a process was truly the campaign of life.”

In 2005, her son, Ken Ross, started the Elisabeth Kübler-Ross Foundation. It is in Scottsdale, Arizona. Her children manage her name and writings through a family partnership.

Impact on Popular Culture

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross has had a big impact on popular culture. This is especially true in music since her death. Many artists and bands have honored her in their work. Songs named "Kübler-Ross" include those by Chuck Wilson (2010) and Elephant Rifle (2010). Other artists like Dominic Moore (2015) and Alp Aybers (2020) also have songs with her name. The band Kübler-Ross (2020) and Norro (2024) have also used her name. In 2008, Matt Elliott released "The Kübler-Ross Model." In 2006, The Gnomes released a song called “Elisabeth Kübler-Ross has Died.”

Many music albums have also been named after her. These include "Kübler-Ross" by Chine Drive (2023) and "Kübler-Ross Soliloquies" by Deadbeat (2023). Other albums are "Kübler-Ross" by Coachello (2024) and "Kübler-Ross (Five Stages of Grief)" by Saint Juvi (2024). The band Spring Offensive used parts of Kübler-Ross's voice in their song "The First of Many Dreams About Monsters" (2010). This song is about grief and death.

Some artists have named albums after Kübler-Ross’s books. "Beyond the Shores (On Death & Dying)" by Shores of Null (2020) is one example. Marina's 2019 album "Love & Fear" was directly inspired by Kübler-Ross's ideas.

Her influence also extends to band names. KÜBLER ROSS is a Swedish punk band started by a former nurse. Another band, Kübler-Ross, is from Glasgow, Scotland. Their album “Kübler-Ross” was nominated for Album of the Year in Scotland in 2021.

See also

In Spanish: Elisabeth Kübler-Ross para niños

In Spanish: Elisabeth Kübler-Ross para niños