Eliza Haywood facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Eliza Haywood

|

|

|---|---|

Playwright and novelist Eliza Haywood, by George Vertue, 1725.

|

|

| Born |

Eliza Fowler

1693 |

| Died | 25 February 1756 |

| Resting place | Saint Margaret's Church near Westminster Abbey in Westminster |

Eliza Haywood (around 1693 – 25 February 1756) was an English writer, actress, and publisher. Her birth name was Elizabeth Fowler. She wrote and published over 70 works during her lifetime. These included novels, plays, poems, and magazines.

Today, Eliza Haywood is known as one of the most important writers who helped create the modern novel in English during the 18th century. People started to become more interested in her work again in the 1980s.

Contents

About Eliza Haywood

Scholars know very little for sure about Eliza Haywood's early life. The only exact date everyone agrees on is when she died. Haywood herself gave different stories about her life. This means her beginnings are still a bit of a mystery.

She was born "Eliza Fowler," but the exact date of her birth is not known. This is because old records are missing. Experts believe she was likely born in 1693. This guess comes from her death date and her age at the time she died. She passed away on February 25, 1756, and was said to be sixty years old.

We don't know much about her family, how much education she had, or her social standing. Some people think she might be related to Sir Richard Fowler. Others believe she was probably from London. But there is no clear proof for any of these ideas.

Her first public record shows up in Dublin, Ireland, in 1715. It lists her as "Mrs. Haywood." She was acting in a play called Timon of Athens; or, The Man-Hater. Haywood later said she was a "widow" and that her marriage was "unfortunate." However, no record of her marriage has ever been found.

Haywood had a long and busy writing career. It started in 1719 with her first novel, Love in Excess. It ended in the year she died with books about good manners. She wrote in almost every type of writing style. She often published her works without using her real name.

Today, Eliza Haywood is seen as a leading female author and businesswoman of her time. She was very hardworking. She wrote novels, poems, plays, and edited magazines. In the early 1720s, "Mrs. Haywood" was very popular in London's novel market.

Eliza Haywood became ill in October 1755. She died on February 25, 1756. She was still publishing works right up until her death. She was buried in Saint Margaret's Church near Westminster Abbey. Her grave does not have a marker.

Acting and Plays

Eliza Haywood started her acting career in 1715. She performed at the Smock Alley Theatre in Dublin. Records from that year show her acting in a play. It was called Timon of Athens; or, The Man-Hater.

By 1717, she was working at Lincoln's Inn Fields for a man named John Rich. Rich asked her to rewrite a play called The Fair Captive. Her first play, A Wife to be Lett, was performed in 1723.

In the late 1720s, Haywood kept acting. She moved to the Haymarket Theatre. There, she joined Henry Fielding in plays that spoke out against the government. In 1729, she wrote a play called Frederick, Duke of Brunswick-Lunenburgh. This play honored Frederick, Prince of Wales. Frederick was the son of King George II. He did not agree with his father's government. So, praising him was a way to show disagreement.

Haywood's biggest success at the Haymarket came in 1733. It was a play called The Opera of Operas. This play was based on Fielding's Tragedy of Tragedies. It had music by J. F. Lampe and Thomas Arne).

After the Licensing Act of 1737 was passed, it became harder to stage new and daring plays. This law limited what could be performed in theaters.

Novels and Stories

Eliza Haywood, along with Delarivier Manley and Aphra Behn, were known as "the fair triumvirate of wit". They were important writers of romantic stories. Haywood's many works changed over time. In the early 1720s, she wrote exciting romance novels. Later, in the 1720s and 1730s, her books focused more on "women's rights and position."

In the 18th century, authors were paid only once for a book. They did not get extra money (royalties) each time a book sold. Because of this, Haywood's novels often had many parts or volumes. A second volume meant a second payment for the author.

Magazines and Non-Fiction

Besides writing popular novels, Eliza Haywood also worked on magazines and books about social behavior. The Female Spectator (1745–1746) was a monthly magazine. Haywood wrote it as a response to another popular magazine called The Spectator.

In The Female Spectator, Haywood wrote using four different characters. She shared her ideas on marriage, children, reading, and education. This was the first magazine written for women by a woman. It is considered one of her most important contributions to women's writing.

She also wrote The Parrot (1746). This magazine led to her being questioned by the government. They were concerned about political statements she made about Charles Edward Stuart. Haywood also wrote Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots (1725). This was a non-fiction work that used storytelling techniques. Her books The Wife and The Husband (1756) were guides for partners in a marriage.

Haywood also wrote interesting stories about a deaf-mute prophet named Duncan Campbell. These included A Spy Upon the Conjurer (1724).

Political Writings

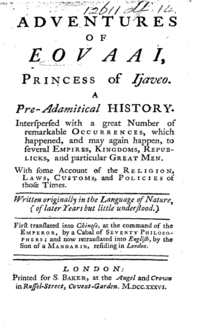

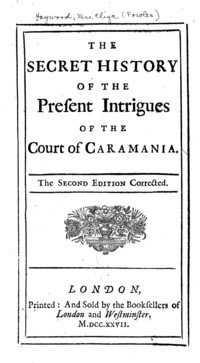

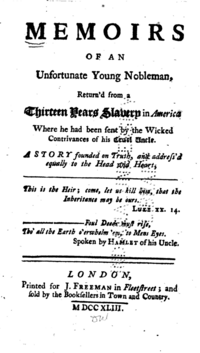

Eliza Haywood was involved in politics throughout her career. She wrote a series of "secret histories." These included Memoirs of a Certain Island, Adjacent to Utopia (1724). Another was The Secret History of the Present Intrigues of the Court of Caramania (1727). Her book Memoirs of an Unfortunate Young Nobleman (1743) told a fictionalized story based on the life of James Annesley.

In 1746, she started another magazine, The Parrot. She was questioned by the government because of political statements in it. These were about Charles Edward Stuart, right after the Jacobite rising of 1745. This happened again with A Letter from H---- G----g, Esq. (1750). She became even more direct in her political writings later on. These included The Invisible Spy (1755) and The Wife (1756).

Translations

Haywood translated eight popular romance novels from other countries. These included Letters from a Lady of Quality (1721). She also translated La Belle Assemblée (1724–1734). With William Hatchett, she translated The Sopha (1743).

As a Publisher

Haywood not only wrote books but also helped publish them. She sometimes worked with William Hatchett. At least nine works were published under her own name. Most of these were sold at her shop, the Sign of Fame, in Covent Gardens.

Some works published by Eliza Haywood include:

- Anti-Pamela by Eliza Haywood (1741)

- The Virtuous Villager by Eliza Haywood (1742)

- A Letter from H[enry] G[orin]g by Eliza Haywood (1749)

In the 18th century, a "publisher" could also mean someone who sold books. Haywood was definitely a bookseller. Many different books were available at her shop.

Works by Haywood

Collections by Eliza Haywood published before 1850:

- The Danger of Giving Way to Passion (1720–1723)

- The Works (3 volumes, 1724)

- Secret Histories, Novels and Poems (4 volumes, 1725)

- Secret Histories, Novels, Etc. (1727)

Individual works by Eliza Haywood published before 1850:

- Love in Excess (1719–1720)

- Letters from a Lady of Quality to a Chevalier (1720) (translation of Edme Boursault's novel)

- The Fair Captive (1721)

- The British Recluse (1722)

- The Injur'd Husband (1722)

- Idalia; or The Unfortunate Mistress (1723)

- A Wife to be Lett (1723)

- Lasselia; or The Self-Abandon'd (1723)

- The Rash Resolve; or, The Untimely Discovery (1723)

- Poems on Several Occasions (1724)

- A Spy Upon the Conjurer (1724)

- The Lady's Philosopher's Stone (1725) (translation of Louis Adrien Duperron de Castera's historical novel)

- The Masqueraders; or Fatal Curiosity (1724)

- The Fatal Secret; or, Constancy in Distress (1724)

- The Surprise (1724)

- The Arragonian Queen: A Secret History (1724)

- The Force of Nature; or, The Lucky Disappointment (1724)

- Memoirs of the Baron de Brosse (1724)

- La Belle Assemblée (1724–1734) (translation of Madame de Gomez's novella)

- Fantomina; or Love in a Maze (1725)

- Memoirs of a Certain Island Adjacent to the Kingdom of Utopia (1725)

- Bath Intrigues: in four Letters to a Friend in London (1725)

- The Unequal Conflict (1725)

- The Tea-Table (1725)

- The Dumb Projector: Being a Surprising Account of a Trip to Holland Made by Duncan Campbell (1725)

- The Fatal Fondness (1725)

- Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots (1725)

- The Mercenary Lover; or, the Unfortunate Heiresses (1726)

- Reflections on the Various Effects of Love (1726)

- The Distressed Orphan; or, Love in a Madhouse (1726)

- The City Jilt; or, The Alderman Turn'd Beau (1726)

- The Double Marriage; or, The Fatal Release (1726)

- The Secret History of the Present Intrigues of the Court of Carimania (1726)

- Letters from the Palace of Fame (1727)

- Cleomelia; or The Generous Mistress (1727)

- The Fruitless Enquiry (1727)

- The Life of Madam de Villesache (1727)

- Love in its Variety (1727) (translation of Matteo Bandello's stories)

- Philadore and Placentia (1727)

- The Perplex'd Dutchess; or Treachery Rewarded (1728)

- The Agreeable Caledonian; or, Memoirs of Signiora di Morella (1728)

- Irish Artifice; or, The History of Clarina (1728)

- The Disguis'd Prince (1728) (translation of Madame de Villedieu's 1679 novel)

- The City Widow (1728)

- Persecuted Virtue; or, The Cruel Lover (1728)

- The Fair Hebrew; or, A True, but Secret History of Two Jewish Ladies (1729)

- Frederick, Duke of Brunswick-Lunenburgh (1729)

- Love-Letters on All Occasions Lately Passed between Persons of Distinction (1730)

- The Opera of Operas (1733)

- L'Entretien des Beaux Esprits (1734) (translation of Madame de Gomez's novella)

- The Dramatic Historiographer (1735)

- Arden of Feversham (1736)

- Adventures of Eovaai, Princess of Ijaveo: A Pre-Adamitical History (1736)

- Alternative title The Unfortunate Princess, or The Ambitious Statesman (2nd edition, 1741)

- The Anti-Pamela; or Feign'd Innocence Detected (1741)

- The Virtuous Villager (1742) (translation of Charles de Fieux's work)

- The Sopha (1743) (translation of Claude Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon's novel)

- Memoirs of an Unfortunate Young Nobleman (1743)

- A Present for a Servant Maid; or, the Sure Means of Gaining Love and Esteem (1743)

- The Fortunate Foundlings (1744)

- The Female Spectator (4 volumes, 1744–1746)

- The Parrot (1746)

- Memoirs of a Man of Honour (1747)

- Life's Progress through the Passions; or, The Adventures of Natura (1748)

- Epistle for the Ladies (1749)

- Dalinda; or The Double Marriage (1749)

- A Letter from H---- G-----, Esq., One of the Gentlemen of the Bedchamber of the Young Chevalier (1750)

- The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless (1751)

- The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy (1753)

- The Invisible Spy (1754)

- The Wife (1756)

- The Young Lady (1756)

- The Husband (1756)

- See also: The Female Spectator (4 vols., 1744–1746). 5th ed., v.3 (London: 1755); 7th ed. (London: 1771)

See also

- List of early-modern British women playwrights

- List of early-modern British women poets