Emancipation of the British West Indies facts for kids

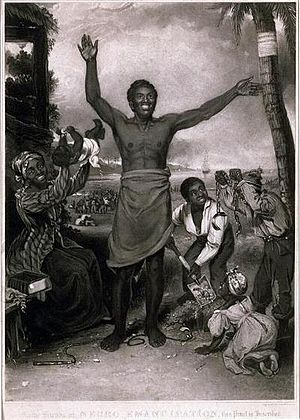

The emancipation of the British West Indies was when slavery ended in Britain's colonies in the West Indies during the 1830s. The British government passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. This law freed all enslaved people in the British West Indies.

After this, a system called "apprenticeship" began. Enslaved people had to keep working for their former owners for four to six years. They received food and housing in return. This system ended in 1838 because the British public demanded it. This completed the process of freedom for enslaved people.

Contents

Why Slavery Ended

Many things led to Britain ending slavery across its empire.

Fighting for Freedom

Enslaved people in the Caribbean often fought back. They rebelled, stopped working, or resisted in other ways. These actions made colonial leaders think about ending slavery. They wanted peace and stability in the colonies.

The Haitian Revolution was a very successful slave uprising in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. This event made British leaders worried about similar revolts in their own colonies.

New Ideas and Activism

New ideas from the Age of Enlightenment and religious groups made many British people question if slavery was right. During the 1700s and 1800s, more and more people wanted to end slavery.

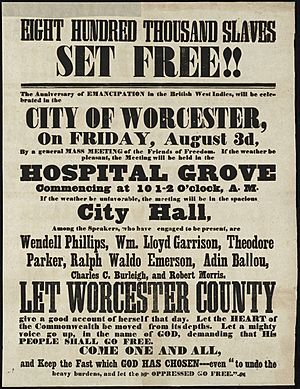

Religious leaders were very important in this fight. Groups like the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society shared pamphlets. These papers showed how cruel slavery was. Millions of signatures were sent to the British Parliament. Many of these came from women's groups. These people put pressure on the British government to end slavery.

Some historians also believe that as capitalism grew, slavery became less profitable. This might have also helped increase support for ending it.

Laws Against Slavery

In 1807, British abolitionists had a partial success. The government passed the Slave Trade Act. This law stopped the buying and selling of enslaved people. But it did not end slavery itself.

Reformers kept pushing for full abolition. The British government finally ended slavery in its colonies with the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. This law started in August 1834. All enslaved people in the British Empire were then considered free.

The British government agreed to pay West Indian plantation owners £20 million. This was to help them change from using enslaved labor to free labor. However, the enslaved people themselves received no money.

In most places, the law turned enslaved people into "apprentices." But in Antigua and Bermuda, the local governments chose to free everyone completely in 1834.

The Apprenticeship System

The Slavery Abolition Act created a system called "apprenticeship." This meant that newly freed people had to keep working for their former owners.

How Apprenticeship Worked

This system was meant to make the change from slavery to freedom easier. But it was also largely about keeping sugar production going in the West Indies.

- Field workers had to be apprentices for six years.

- Household workers had to work for four years.

- Children under six years old were freed right away.

All apprentices' names were put on a list. This list showed how long they had to serve.

Apprentices had to work up to 45 hours a week without pay. If they worked more, they got paid for those extra hours. The idea was that this paid work would teach them how to be good workers. In return for their unpaid work, they received food, housing, clothes, and medical care. They were not allowed to work on Sundays. If an apprentice could afford it, they could buy their freedom early.

The British government appointed special magistrates to oversee this system. These officials were supposed to protect the interests of the freed people. However, colonial leaders were worried about how former slaves would react. So, they created police districts to keep order.

Workhouses were set up in each district. These were run by magistrates and justices of the peace, who were often plantation owners. Freed people could be sent to workhouses if they refused to work or broke other rules. The law banned plantation owners from using whips. The government was now in charge of punishing workers. But owners could still send apprentices to workhouses to control them.

Conditions in workhouses were very harsh. Apprentices faced hard labor and physical punishment. Treadmills were common. These were like large wheels with steps. Prisoners had to step on them for hours. This machine did not produce anything. Officials said it was to "reform" and "discipline" prisoners. Plantation owners also supported treadmills. They believed former slaves would not work hard without harsh punishment. Even women were sent to workhouses and forced onto treadmills.

Apprentices' Resistance

When news of the Abolition Act reached the colonies, enslaved people celebrated. But they soon realized that freedom would be gradual. They protested the apprenticeship system. They demanded immediate freedom. They had worked under slavery and were doing the same tasks now. They felt they did not need a supervised system.

Freed people wanted to live their own lives and spend time with family. They wanted to choose their own work hours, employers, and types of jobs. Many apprentices across the West Indies refused to work. They went on strike. For this, many were arrested, whipped, and sent to prison.

Women often faced special challenges. Before emancipation, owners encouraged pregnant women to have children. This was because children of enslaved women became the owner's property. Under apprenticeship, owners no longer had rights to women's children. So, they stopped offering special help to pregnant women or new mothers. Women were expected to work even when pregnant or with small children. Other freed people demanded that these women be excused from hard field work.

Sometimes, apprentices' protests led to changes. In Trinidad, apprentices got a five-day work week. Masters had to care for freed children. Workers were paid for work done on Saturdays.

A few apprentices tried to buy their freedom. Some succeeded. Courts set high prices for freedom. This made it hard for most apprentices to buy their way out. But as the end of apprenticeship got closer, some plantation owners agreed to lower prices. This way, they still got some money. They also hoped it would encourage apprentices to keep working after they were fully free.

James Williams' Story

A Narrative of Events, since the First of August, 1834, by James Williams, an Apprenticed Labourer in Jamaica is a rare firsthand account by a former slave. It was published in 1837. This pamphlet was sold and reprinted across Britain and Jamaica.

The story was very important in the campaign against apprenticeship. This campaign was led by Joseph Sturge and other abolitionists. They believed apprenticeship was just slavery in another form. In 1836, Sturge went to Jamaica. He wanted to learn about the labor system. There, he met James Williams, an apprentice. Williams shared his experiences. Sturge had Williams' story written down and published it. He hoped to show the British public what was happening and gain support for immediate freedom.

Williams' story described his harsh experiences in Jamaica. He explained how he was treated unfairly by his master. He told how workhouse prisoners were tied to treadmills. They were forced to "dance" on the machine after long workdays and were severely whipped. Williams also talked about how forced labor hurt families. He mentioned that officials could not control the system well. He also described the poor living and working conditions.

The book was popular and widely read in Britain. But it also caused a strong reaction in the West Indies. A pro-plantation newspaper in Jamaica called it propaganda. In response, anti-apprenticeship groups published other apprentice interviews. This helped support Williams' claims.

Williams' story was very helpful because it named specific people and places. This made his claims easy to check. In 1837, the Colonial Office asked Sir Lionel Smith, the governor of Jamaica, to investigate Williams' claims. A commission was set up to interview apprentices, magistrates, and workhouse overseers. This commission confirmed many of Williams' claims. Their findings were published in a special report.

Apprenticeship Ends

Williams' story, other bad reports, and investigations into the workhouses led to change. Local fears of rebellion and pressure from the British public also played a part. Because of this, colonial assemblies ended the apprenticeship system early. By 1838, it was completely abolished.

Full Freedom

After 1838, the political rights of newly freed people were discussed. Britain's colonial secretary, Lord Glenelg, wanted social and political equality. He suggested that colonial governors check laws to remove any that were unfair. However, local plantation owners still had a lot of power. They often did not want to give many rights to the freed people.

Changes in Society

Missionaries and religious leaders tried to change the culture of former slaves. They believed slavery had made them "backward." They encouraged freed people to get legally married and adopt European family styles. They thought this would help them gain respect. This meant men should be heads of households and provide for their families. Women were expected to raise children and do housework.

Freed men and women did adopt some of these ideas. Marriage between former slaves increased. But they also valued their wider family ties, like brothers, sisters, and parents. Having children outside of marriage was not uncommon or seen as bad.

Missionaries also started schools. They encouraged freed people to become Christians and attend church. Most people did not adopt all European ways. Instead, they mixed parts of the European model with their own African traditions. Former slaves often enjoyed dancing, carnivals, and gambling. Authorities did not like these activities. They thought these were against their reform efforts. Historians suggest that freed people enjoyed these activities to "test the limits of their freedom."

Land and Work

Sugar and other crops were still very important to the economies of the British West Indies. Farming needed many workers. Former slaves were expected to do this work. But some freed people did not want to work on their old plantations. They wanted to work on their own terms. Plantation owners thought this meant they were lazy. But many workers refused to work because of low wages. Others wanted different jobs, like skilled trades.

Many freed West Indians wanted to become independent farmers. They wanted to grow food for their families and sell some for profit. They bought, rented, or settled on land whenever possible. Some officials and missionaries supported this. They thought land ownership would make former slaves independent.

However, in some areas, colonial officials stopped freed people from getting land. They used laws, high taxes, and rules that required buying large amounts of land. Most former slaves could not afford this. Freed people who lived on government land without permission were forced off. Their small farms, used for food or selling crops, were sometimes burned or taken away. Local laws said that anyone not farming was a "vagrant" and could be jailed. These rules limited independent farming. They forced many former slaves to work for wages on plantations.

The need for cheap labor also led plantation owners to bring in new workers. They imported indentured laborers from India. British abolitionists tried to stop this practice, but they were not as successful as they had been before.

Women and Work

After emancipation, many black women stopped working in the plantation fields for wages. Some left completely, while others worked less. This shows that freed people did adopt some gender roles. However, this did not mean women avoided all work outside the home. Their extra income was vital for their families. So, women often grew food at home and sold it in the market. Meanwhile, their male relatives worked on the plantations.

Legacy

By the mid-1800s, just years after emancipation, the Caribbean's economy began to struggle. Sugar prices dropped, and plantations in places like Jamaica closed down. In Jamaica, sugar production in 1865 was half of what it was in 1834. These changes led to huge unemployment, high taxes, and low wages. Poverty increased. Living conditions on the islands did not improve much for many decades.

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |