Enrique de Villena facts for kids

Enrique de Villena (born 1384, died 1434) was a Spanish nobleman, writer, and poet. He was also known as Henry de Villeine and Enrique de Aragón. Enrique was the last true member of the House of Barcelona, a powerful royal family in Aragon. When he couldn't get political power, he focused on writing instead. Some people, including King Alfonso V of Aragon and King John II of Castile, were suspicious of him because they thought he was a necromancer (someone who practiced magic).

Contents

Enrique's Early Life and Family

Enrique de Villena was born in Torralba de Cuenca, a town in Castile. After his father, Pedro de Aragón y Villena, passed away, Enrique moved to the court of Aragon. There, his grandfather, Alfonso de Aragón, raised him. Alfonso was the first marquess of Villena, a high-ranking noble title. He claimed to be a descendant of King James II of Aragon.

At court, Enrique met many smart people and learned a lot about mathematics, chemistry, and philosophy. The queen of Aragon, Violant of Bar, noticed how talented he was. She invited him to study at the royal court in Barcelona. This helped Enrique meet important Catalan writers and set him up for a promising future.

Challenges and New Paths

Towards the end of the 1300s, Enrique's grandfather started to lose his power in the Castilian court. By 1398, Alfonso was no longer the marquess of Villena. This upset both Alfonso and Enrique. Alfonso spent years trying to get his grandson back into that important position. Meanwhile, Enrique simply called himself the Marquess of Villena on official papers, even though it wasn't legally correct.

Historians believe Enrique traveled to Castile in the early 1400s. He settled there and married María de Albornoz, a wealthy woman from Cuenca. Enrique continued to rise in society. His cousin, King Henry III of Castile, gave him the titles of count of Cangas and Tineo.

In 1404, Enrique decided to leave the court and travel the world. That same year, he tried to become the leader of the Order of Calatrava. This was a very respected religious and military group. To join, Enrique divorced his wife and gave up his title as count. He officially became a friar (a type of monk) of Calatrava. The King of Castile ordered the commanders of Calatrava to make Enrique their master. However, this job didn't suit Enrique well. He was smart, but not good at politics. Soon, he was removed from his leadership role.

Later Years and Focus on Writing

Enrique had a stroke of good luck when his cousin, Infante Ferdinand of Castile, became King of Aragon in 1412. Enrique enjoyed several peaceful years working as Ferdinand's personal assistant. But when King Ferdinand I died in 1416, Enrique went back to Castile. He spent the next few years at his wife's family estates in Cuenca, taking care of family business.

He gained the lordship of Miesta. Realizing he wasn't suited for fighting or political life, he dedicated himself to literature. He had two daughters born outside of marriage. One of them, Elionor Manuel, later became a nun named Isabel de Villena in a convent in Valencia. She became an abbess (the head of a convent) in 1463 and wrote a book called Vita Christi.

From 1420 to 1425, Enrique wrote Arte cisoria and other important papers. In 1426, King Alfonso the Magnanimous took away Enrique's promised inheritance as Duke of Gandía. Instead, he gave the position to his own brother. Because of this, Enrique faced money problems and depended on his nephew for support until he died in 1434.

Enrique's Reputation and Interests

Enrique de Villena had many different talents and interests, which you can see in his writings. In his book Arte de Cisoria (The Art of Carving), he carefully described the tools, steps, and rules for carving meat at the table. He learned this from watching and working at the courts of his cousin, King Henry III of Castile, and his nephew, King John II of Castile.

His understanding of 15th-century medicine is clear in his work Tratado de la fascinación o de aojamiento (Treatise on the Evil Eye). In this book, he talked about where the evil eye came from. He also shared traditional and "modern" ways to prevent, diagnose, and cure this illness. More medical knowledge is found in his Tratado de la lepra (Treatise on Leprosy). In Tratado de la consolación (Treatise on Consolation), we see his understanding of psychology.

It's said that Enrique spent a lot of time studying alchemy (an old form of chemistry), astrology (studying how stars affect people), philosophy, and mathematics. This led to his widespread reputation as a necromancer (someone who practices magic, often involving talking to the dead). Like other famous figures, he was rumored to have built a brazen head that could answer his questions.

After Enrique died in 1434, the king ordered Bishop Lope de Barrientos to check his library. The bishop had many of Enrique's books burned. This made the public even more sure that Enrique was involved in witchcraft. A few of the remaining books went to the poet Santillana, and the rest went to the king.

Enrique's Writings

Enrique de Villena's literary works were quite varied. Perhaps his most popular book among Spanish readers was his version of Los doce Trabajos de Hércules (The Twelve Works of Hercules). This book used ideas from Greek mythology but also added Christian meanings. Enrique combined these ideas throughout the work.

First written in Catalan and then changed into Castilian, the book had clear moral messages. Enrique felt these messages were important for Spain at the time. Twelve Works is divided into twelve chapters, and each chapter has four parts. Enrique believed that good stories could both entertain readers and encourage them to act virtuously. Written in 1417, Twelve Works of Hercules helped build Enrique's reputation as a writer.

Villena's Arte de Trovar is a book about the rules of troubadour poetry. Troubadour poetry was a type of song and poetry popular in the Middle Ages. This work, like Enrique's other writings, was very detailed and sometimes difficult. It focused on complex rules for versification (how lines of poetry are structured). Enrique saw these poetic structures as a "true and unchanging order of things." He believed a poet's skill was in making their words fit these rules. Arte de Trovar shows the important cultural exchange between Catalonia and southern France, where troubadour poetry came from. It also shows Enrique's fondness for the old, chivalrous world of troubadour stories. Arte de Trovar was finished between 1417 and 1428.

Enrique also translated famous works like Virgil's The Aeneid and Dante's Divine Comedy into Castilian. He was one of the first to translate Dante's poem into another everyday language and Virgil's epic poem into a Romance language (1427–28). He faced the challenge of keeping the deep meaning of The Aeneid while making it understandable to readers who weren't scholars. Along with advice for new readers, his translation explained how the ancient stories could still apply to Castilian society. His translations of these classical works were widely read by a growing group of noble readers, and Enrique was a very important person in this group.

Astrology and Esoteric Studies

Enrique de Villena's works on hidden or secret knowledge include his Treatise on Astrology (1438) and Treatise on the Evil Eye (1425). In the first book, Enrique used ideas from the Bible to support astrology and magic. He even said that Moses was an astrologer and used magic with talismans. He argued that Zoroaster was Moses's teacher and the founder of magic. This idea was later explored by other thinkers in the 15th century.

In his Treatise on the Evil Eye, Enrique also defended Jewish practices like Kabbalah (a mystical tradition) for curing the evil eye. This was many years before other European scholars became interested in Kabbalah.

Enrique's Lasting Impact

Enrique de Villena's deep interest in science and his knowledge of astrology and other mystical systems gave him the reputation of a necromancer during his lifetime. This made some people question his works. However, today, experts see Enrique as one of the most important thinkers in Castile during the 15th century.

Enrique showed characteristics of humanism (a way of thinking that focuses on human values and achievements) through his translations of classical works. He helped bring Italian humanist ideas and Latin culture into Castile. This started a movement to translate classical works into modern languages. This way, more people, not just Latin scholars, could read and enjoy them.

Enrique strongly believed that poetry was important for creating smart and educated leaders. He tried to teach his readers about different aspects of morality in his texts. He wanted to influence the Castilian court and nobles to be virtuous and polite.

His most important classical translation was Virgil's Aeneid, finished in 1428. It was one of the first complete translations of this work into a Romance language. He translated the work and added comments to help readers understand difficult parts. He also gave simple explanations to teach Castilian society proper behaviors for courtiers.

The accusations of magic and the strong influence of Italian Humanism made Enrique a bit controversial. This controversy actually made him more popular, as later authors became interested in him. Enrique often appears as a character in literature. For example, in El doncel de don Enrique el Doliente, Mariano José de Larra shows Enrique as an evil character. But in Lope de Vega's Porfiar hasta morir, Enrique is shown as a hero who works for justice. There isn't one clear picture of what Enrique was really like. His literary achievements have lasted through time, but the mystery around his life remains. Still, he is seen as a pioneer in thinking who showed good civic values and wrote with beautiful poetry.

| Preceded by Gonzalo Núñez de Guzmán |

Grand Master of the Order of Calatrava 1404–1407 |

Succeeded by Luis González de Guzmán |

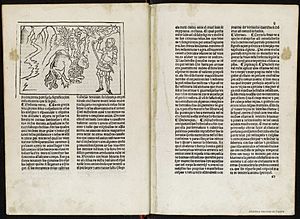

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Enrique de Villena para niños

In Spanish: Enrique de Villena para niños