Ewald Hering facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ewald Hering

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 5 August 1834 Alt-Gersdorf, Kingdom of Saxony

|

| Died | 26 January 1918 (aged 83) Leipzig, Kingdom of Saxony

|

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | Leipzig University |

| Known for | Canals of Hering Hering illusion Hering–Breuer reflex Hering–Hillebrand deviation Hering's law of visual direction Hering's law of equal innervation Traube–Hering–Mayer waves Hyperacuity Opponent-process theory Organic memory+ |

| Awards | Pour le Mérite (1911) ForMemRS (1902) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physiology |

Karl Ewald Konstantin Hering (born August 5, 1834 – died January 26, 1918) was a German scientist. He was a physiologist, which means he studied how living things work. Hering did a lot of important research on how we see. This included how we see colors, how our two eyes work together, and how our eyes move. He also studied something called hyperacuity, which is about seeing very fine details.

In 1892, he came up with a famous idea called the opponent color theory. This theory explains how our brains process colors in pairs. Hering was born in a place called Alt-Gersdorf in the Kingdom of Saxony. He later studied at the University of Leipzig. He also became the first leader of the German Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Studies

Ewald Hering was born in Altgersdorf, Germany. He grew up in a family that probably didn't have much money. His father was a Lutheran pastor. Hering went to high school in Zittau. In 1853, he started studying at the University of Leipzig. There, he learned about philosophy, animals (zoology), and medicine. He earned his medical degree in 1860.

It's not completely clear how Hering learned to do scientific research. At that time, Johannes Peter Müller was a very famous physiologist in Germany. Hering tried to study with him but was turned down. This might have made him dislike Hermann von Helmholtz, who was Müller's student. However, in Leipzig, other scientists like E. H. Weber and G. T. Fechner were doing new studies. These studies helped create a field called psychophysics, which looks at how our minds and bodies connect. Even though Hering didn't officially study with them, he later said he was a "student of Fechner."

After finishing his studies, Hering worked as a doctor in Leipzig. He didn't have much time or money for research. But he still started studying binocular vision. This is how our two eyes work together to see. He also looked at the "horopter." This is a special curved line in space where objects appear to be at the same distance from both eyes. Hering surprised everyone when he published his own mathematical way to figure out the horopter. He did this on his own, even though he wasn't well-known. Another famous scientist, Hermann von Helmholtz, had also worked on this. Hering even pointed out some small math mistakes in Helmholtz's work!

University Positions

After his early success, Hering became a professor of physiology. He taught at a military academy in Vienna until 1870. With better tools and resources there, he did important studies. These included research on the heart and breathing systems. In 1870, he moved to the University of Prague. He took over from another famous scientist, Jan Evangelista Purkinje. Hering stayed in Prague for 25 years.

While in Prague, he got involved in arguments between Czech and German professors. The Czechs wanted the university to be taught in their language. In 1882, a separate German university was created. It was called the Charles-Ferdinand University. Hering became its first leader.

Later in his life, Hering returned to Germany. In 1895, when he was 61, he became a professor at the University of Leipzig. He retired in 1915 and passed away three years later from tuberculosis.

Research

How We See with Two Eyes

Hering studied many things about vision. His work on binocular vision was especially important. He figured out the shape of the horopter, almost at the same time as Helmholtz. Hering's method was more modern and elegant. Even Helmholtz said Hering's approach was "very elegant." Later, Hering tested the horopter in real life. He, Helmholtz, and Hillebrand noticed that the real horopter didn't exactly match the theoretical one. This difference is now called the Hering–Hillebrand deviation.

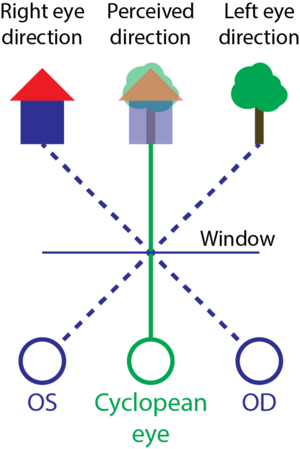

Hering is also known for his Law of Visual Direction. This law explains how we figure out where an object is in space, based on our own position. Other scientists like Alhazen (in 1021) and Wells (in 1792) had similar ideas, but Hering's was unique.

Seeing Fine Details (Hyperacuity)

Hering did important work on what we now call hyperacuity. This is our amazing ability to see tiny details that are even smaller than the light-sensing cells in our eyes. In 1899, he wrote about this in his paper "On the Limits of Visual Acuity." He looked at data from other scientists. They found that in some vision tasks, like seeing if two lines are perfectly aligned, we can see details much smaller than our receptor cells.

Hering explained this using a model. He showed how our eyes combine information from many receptor cells. Even with tiny, quick eye movements called microsaccades, our brain can figure out the exact location of things with super high precision. This idea is still believed to be true today.

How Our Eyes Move

Hering also studied how our eyes move. He came up with Hering's law of equal innervation. This law says that when our eyes move, the signal sent to both eyes is always equal in strength. However, the eyes don't always move in the same direction.

For example, our eyes can move together in the same direction. This happens during saccades (quick jumps) or smooth pursuit (following a moving object). Or, they can move in opposite directions. This happens during vergence eye movements, like when your eyes turn inward to look at something close.

Hering's law is best shown with something called Müller's stimulus. Imagine a target that moves for one eye but not the other. You might think only the eye that saw the target move would adjust. But Hering's law predicts that both eyes will move together first. Then, they will adjust to focus on the target. This means the eye that didn't see the target move will actually move away and then back to it! This prediction was proven true by experiments. However, scientists now know there can be some differences from Hering's law.

How We See Colors

Hering had different ideas about color vision than other leading scientists like Thomas Young, James Clerk Maxwell, and Hermann von Helmholtz. Young thought that color vision was based on three main colors: red, green, and blue. Maxwell showed that you could make any color by mixing these three. Helmholtz thought this meant humans had three types of color receptors in their eyes. He believed white and black just showed how much light there was.

Hering, however, believed our visual system works using a system of color opponency. He found evidence for this from experiments where people adapted to colors. He also noticed that in language, you can't combine certain color names. For example, you don't say "reddish-green" or "yellowish-blue." In Hering's model, we see colors through three pairs of opposite colors: red-green, yellow-blue, and white-black.

Later, in 1905, Johannes von Kries came up with the zone theory. This theory combined both ideas. It said that the Young-Helmholtz theory explains how light interacts with our eye's receptors. And Hering's theory explains how our brain processes that information. In 1925, Erwin Schrödinger also wrote about how these two theories are connected.

Both theories have strong scientific proof. The puzzle was solved when scientists found special "color-opponent" cells in our eyes and brains. We now know that our eyes have three types of color-sensitive receptors, just as Young, Maxwell, and Helmholtz suggested. Then, these receptors send signals that are combined into three color-opponent channels, just as Hering proposed. So, both Hering's and Young-Helmholtz's theories are correct!

Other Contributions to Physiology

Hering also made important discoveries in physiology. With his student Breuer, he discovered the Hering–Breuer reflex. This reflex explains how our breathing works. When our lungs fill with air, a signal is sent that makes us breathe out. Then, when our lungs empty, a new signal makes us breathe in. It's like an endless loop! He also showed the Traube-Hering reflex. This reflex means that when our lungs fill with air, our heart beats faster.

Other Interesting Research

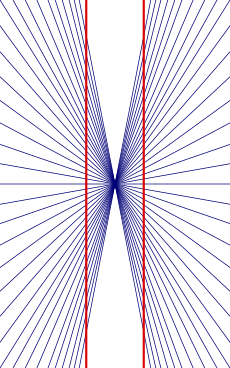

In 1861, Hering described an optical illusion that is now named after him – the Hering illusion. Imagine two straight, parallel lines. If you put them in front of a background that looks like bicycle spokes, the lines will appear to bend outwards. The Orbison illusion is a similar trick, and the Wundt illusion creates a similar, but opposite, effect.

Hering also suggested an idea called organic memory in 1870. He thought that memories could be passed down from parents to children through special cells.

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |