Expeditions and the protection of Yellowstone (1869–1890) facts for kids

Yellowstone National Park is a truly amazing place, full of geysers, hot springs, and incredible wildlife. But how did this special place become a national park? It wasn't always known to everyone. From 1869 to 1890, brave explorers, scientists, and even a president ventured into the Yellowstone region. Their journeys helped people understand how wonderful Yellowstone was, leading to its creation as the world's first national park in 1872. These expeditions also helped protect its natural treasures for future generations.

Contents

Early Explorations: Before the Park (1869-1871)

Before Yellowstone became a national park, its rivers, waterfalls, lakes, mountains, and geysers were mostly unknown. A few important trips helped share its wonders with the world.

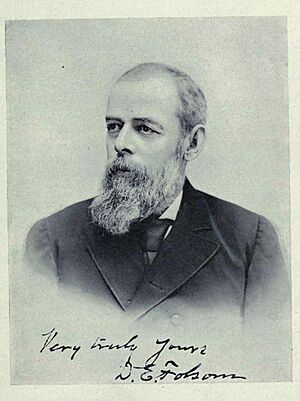

Cook–Folsom–Peterson Expedition (1869)

The Cook-Folsom-Peterson Expedition in 1869 was the first organized group to explore the area that became Yellowstone National Park. This trip was paid for by private citizens: David E. Folsom, Charles W. Cook, and William Peterson. They were from a gold mining town in Montana. Their written journals and stories inspired others to organize more expeditions, especially the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition the next year.

Washburn–Langford–Doane Expedition (1870)

The Washburn Expedition of 1870 explored the region that would soon become Yellowstone National Park. It was led by Henry D. Washburn and Nathaniel P. Langford. The U.S. Army provided an escort led by Lt. Gustavus C. Doane. This group followed a similar path to the Cook–Folsom–Peterson Expedition from the year before.

During their journey, the explorers made detailed maps and notes about Yellowstone. They explored many lakes, climbed mountains, and observed wildlife. They visited the Upper and Lower Geyser Basins. After watching one geyser erupt regularly, they named it Old Faithful, because it erupted about once every hour.

The first widely shared stories about Yellowstone came from this expedition. Langford gave talks about the trip in the eastern United States. He also published his famous article, Wonders of the Yellowstone, in Scribners magazine in May 1871. Lt. Doane also shared his official report with the Department of War.

Hayden Geological Survey (1871)

The Hayden Geological Survey of 1871 explored the Yellowstone region just before it became a national park. This important survey was led by geologist Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden. In the spring of 1871, Hayden chose 32 people for his team. This group included William Henry Jackson, a photographer, and Thomas Moran, an artist.

This survey was the first one funded by the U.S. government to explore and document Yellowstone's features. The amazing photos and paintings from this trip played a big part in convincing the U.S. Congress to create the park. Nathaniel P. Langford, who was part of an earlier expedition and became Yellowstone's first superintendent, later wrote about the importance of Hayden's work. He said that the park's creation was thanks to the Cook-Folsom expedition, the Washburn expedition, and the Hayden expedition.

Heap-Barlow Expedition (1871)

Another important expedition in 1871 was the Heap-Barlow Expedition. This survey also contributed to the growing knowledge of the Yellowstone area.

Later Expeditions: Protecting the Park (1872-1890)

Even after Yellowstone became a park, much of it was still unexplored. Protecting its resources was also a big challenge. These later expeditions helped people learn more about the park and led to stronger laws to keep it safe.

Hayden Geological Surveys (1872 and 1878)

Geologist Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden continued his important work in Yellowstone with more surveys in 1872 and 1878. These follow-up expeditions helped to further map and understand the park's unique geology.

Belknap Tour (1876)

In 1876, William W. Belknap, who was the U.S. Secretary of War, visited Yellowstone National Park. He spent two weeks exploring the park, following the same route as the 1870 Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition. Lt. Gustavus C. Doane, who had guided the Washburn party, was his guide again.

After his trip, Secretary Belknap became concerned about damage happening in the park. A letter from a Montana official in 1876 mentioned that "spoliations in the park are great" and that "several of the geysers are now nearly ruined." This showed the urgent need for better protection.

Snake River Expedition (1876)

In the fall of 1876, Lt. Gustavus C. Doane planned an exploration of the Snake River regions south of Yellowstone. He hoped this trip would bring him recognition for his discoveries. Doane decided to take his soldiers over the Yellowstone plateau in early winter.

The expedition faced many challenges. They traveled through deep snow and brutal cold. Their boat was damaged on Yellowstone Lake and later completely wrecked on the Snake River. The group ran critically short of supplies and faced extreme conditions. They eventually reached safety, but the expedition did not achieve its goals due to the harsh winter weather and difficult terrain. This was Doane's last major exploration in the Yellowstone area.

President Chester A. Arthur's Expedition (1883)

In 1883, President Chester A. Arthur was encouraged to take a break from his busy job. Senator George Vest suggested a trip to the new Yellowstone National Park. In August, President Arthur visited the park for two weeks without any journalists. He was the first sitting U.S. President to visit Yellowstone. Frank Jay Haynes, who later became the park's official photographer, was chosen to photograph the trip.

Senator Vest was very concerned about businesses trying to take unfair control of park services. He helped pass laws that required the Secretary of Interior to get Senate approval for park contracts. This helped prevent corruption. Senator Vest was known as the "Self-appointed Protector of Yellowstone National Park." His encouragement of President Arthur's trip brought national attention to Yellowstone and helped protect it.

Hague Geologic Surveys (1883-1889)

In 1883, Arnold Hague, a geologist, became the lead geologist for the Yellowstone National Park survey. He started his fieldwork in August with a large team of assistants. This team included geologists, a physicist, a chemist, and a photographer, William Henry Jackson. The completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad that summer brought more attention to the park's natural wonders.

Hague played a very important role in developing and protecting Yellowstone. He pushed government officials in Washington to understand the park's importance. He advised on how to manage the park to preserve its features, protect wildlife, and maintain it as a forest reserve and a source for major rivers. He strongly believed in keeping the park's natural beauty untouched. He also fought against plans to build a railroad inside the park. His detailed geological studies of the geysers and hot springs helped us understand the region's unique volcanic rocks. His fieldwork continued for seven seasons, from 1883 to 1889.

Schwatka Winter Expedition (1887)

In December 1886, Arctic explorer Frederick Schwatka planned a winter tour through Yellowstone. This expedition was supported by the New York World newspaper and The Century Magazine. The group started their journey on skis and snowshoes in January 1887. They pulled sleds filled with gear.

While Schwatka had to turn back due to the extreme cold and high elevation, Frank Jay Haynes and three other guides decided to continue. They visited the lower and upper geyser basins and Yellowstone Falls. They faced extreme weather challenges, getting stuck for 72 hours in a blinding snowstorm with little food or shelter. Despite the difficulties, Haynes returned with 42 photographs of Yellowstone in the middle of winter. These were the first-ever winter photos of the park.

Major Protective Measures Enacted

When Yellowstone National Park was created in 1872, there were no specific laws to protect its wildlife. In the early years, people could hunt animals freely. In January 1883, Columbus Delano, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, issued rules that stopped the hunting of most park animals. However, these rules did not apply to animals like wolves, coyotes, bears, or mountain lions.

When the U.S. Army took over managing the park on August 20, 1886, Captain Moses Harris, the first military superintendent, banned all public hunting. He also made sure that only park staff could control predators.

The Lacey Act of 1894: Protecting Park Wildlife

In March 1894, a poacher named Edgar Howell was caught by Captain G. L. Scott of the U.S. Army for killing Bison in the park. However, there were no laws to prosecute Howell, so he could only be temporarily held and removed from the park.

Soon after, park photographer Frank Jay Haynes, author Emerson Hough, and guide Billy Hofer met Captain Scott and Howell. Haynes took photos of the encounter, and Hough sent a story to his publisher, Forest and Stream. This story prompted George Bird Grinnell, the editor of Forest and Stream, to ask Congress for a law to punish crimes in Yellowstone. This led to the creation of the Lacey Act of 1894.

Congressman John F. Lacey was a strong supporter of Yellowstone National Park. In 1894, he sponsored a law to give the Department of Interior the power to arrest and prosecute people who broke laws in the park. In May 1894, Congress passed An Act To protect the birds and animals in Yellowstone National Park, and to punish crimes in said park, and for other purposes. This law became the foundation for all future law enforcement in the park. It also led to the appointment of John W. Meldrum as the first U.S. Commissioner in Yellowstone, a position he held for many years.

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |