Ferrer Center and Colony facts for kids

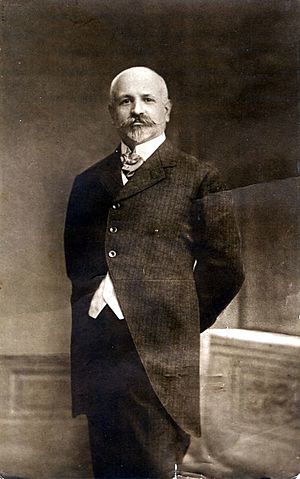

The Ferrer Center and Stelton Colony were special places created to honor Francisco Ferrer. He was a teacher who believed in freedom and new ways of learning. The goal was to build a school in the United States based on his ideas, called the Escuela Moderna.

After Ferrer's death in 1909, many people around the world were upset. A group of people in New York who believed in freedom and justice formed the Ferrer Association in 1910. Their main place was the Ferrer Center. It was a lively spot for art, talks, and performances. It also housed the Ferrer Modern School. This school was different because it let children learn freely, without strict rules or old-fashioned lessons. The Center moved several times in New York City to find a good place for kids to play. After some trouble and police involvement, some members decided to move the school to the countryside.

In 1914, the school moved to what became the Ferrer Colony in Stelton, New Jersey. This was about 30 miles from New York City. The colony was built around the school. People could buy their own plots of land. This meant they were free to sell their land and leave the colony whenever they wanted. They hoped this colony would inspire a national movement for free and open education. The school had some challenges at first. It changed leaders a few times. Elizabeth and Alexis Ferm led it for the longest time. The school finally closed in 1953. It had been a model for other short-lived Ferrer schools across the country and was one of the longest-lasting.

Contents

The Ferrer Center

In 1909, Francisco Ferrer, a teacher and thinker who believed in freedom, was executed in Spain. This made him a hero to many. His ideas led to new schools being started around the world. These schools were like his Escuela Moderna. One such school was started in New York.

On June 12, 1910, 22 people who believed in freedom and justice started the Francisco Ferrer Association in New York City. They created a "cultural center" and an "evening school." This grew into a special "day school" for children. Eventually, it led to a colony outside New Brunswick, New Jersey. The association lasted over 40 years. It had three main goals: to share Ferrer's writings, to hold meetings on the anniversary of his death, and to start schools like his across the United States.

The Ferrer Center, the Association's main building, was a hub of activity. It hosted many cultural events. There were talks about books, debates on important topics, and performances of new art. People also enjoyed social dances and classes. The Center was open to new ideas. Even though many teachers didn't like formal school rules, they still taught regular subjects. Famous people taught there. Painters Robert Henri and George Bellows taught drawing. Will Durant taught the history of ideas. The Center also had evening English classes. These often discussed history and current events. One group even studied Esperanto, a language created to be easy to learn. Weekend talks featured speakers like journalist Hutchins Hapgood and poet Edwin Markham. A talk by lawyer Clarence Darrow brought in hundreds of people. Other well-known people connected to the Center included Jack London and Upton Sinclair.

In late 1914, a folklorist named Moritz Jagendorf started a "Free Theatre" at the Center. This group performed new plays, including one by Lord Dunsany. They also put on their own plays that explored social themes. The theater had very little money. Some performers found it hard to speak English. Other theater groups from Greenwich Village also performed there.

The Center was a friendly and diverse place. A historian named Laurence Veysey said it was one of the most open and exciting small places in the country. People from many different countries came together there. The Center's focus on freedom and justice made it a safe place for people who wanted to change society. It helped children from the 1912 Lawrence textile strike. It also supported efforts to help people who didn't have jobs. The Center started when many people were becoming interested in new ideas about society. This was a time of hope. By 1914, hundreds of adults were members of the Center. Jewish people made up the largest group of its many nationalities. The Ferrer movement in New York brought together Jewish immigrants, who valued education, and Americans who were eager to teach.

Most of the early leaders of the Association and the Modern School were Americans born in the country. Only Joseph J. Cohen was an immigrant, and he joined later. Others included Leonard Abbott, who was the first president, and Harry Kelly. The Center inspired journalist Hutchins Hapgood to write about Yiddish culture. Art dealer Carl Zigrosser said the Center helped him understand New York society better than books ever could.

Some members of the association decided to move the school to the countryside.

The Center inspired other schools across the United States. There were Ferrer schools in Chicago, Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, and Seattle. But most of these schools closed after a few years. The schools in Stelton and Mohegan, however, lasted for decades.

The New York Modern School

As planned, the Ferrer Association opened a day school for children in the Ferrer Center in October 1911. The New York Ferrer Modern School was inspired by Ferrer's memory. It wasn't a copy of his exact methods. The school's founders were driven by their strong feelings about Ferrer's death. They believed his ideas could bring freedom. But they didn't try to copy everything he did. The American movement for new ways of teaching, called progressive education, likely influenced them more. Also, education was very important in Jewish culture. People who had moved from Europe believed that schools could help change the future. They wanted their children to share their values.

The school's early style was flexible and open. The Association wanted to "rebuild society based on freedom and justice." So, the founders wanted their school to let children grow freely. They believed this freedom would help children develop a sense of social fairness. The Association believed in free expression and sharing ideas. The school was meant to be a safe place from typical American ideas. It was also a force to help bring about cultural and social change.

The Association members didn't always agree on school rules. But they all believed that education was about helping children discover their natural talents. It was not about forcing them to believe certain things. The founders didn't have much experience teaching or parenting. They had taught in some Sunday schools. But they didn't trust traditional authority. They would have long debates that didn't always lead to decisions. Some members even got involved in the classrooms, which bothered others. Teachers were not expected to follow any religious or social rules. Instead, they needed to "have the spirit of freedom" and answer children's questions honestly. Teachers were paid little and often left. No principal stayed longer than a year between 1911 and 1916.

The Ferrer Modern School also faced challenges with its buildings. The Center's first location at 6 St. Mark's Place was chosen quickly. It wasn't good for a day school because it lacked outdoor play space. So, it moved to 104 East Twelfth Street in 1911. This new place had an outdoor play area. But the building still lacked standard school equipment. It was also harder for families who believed in freedom to reach. So, in October 1912, the school moved again. This time it went to an older building in East Harlem, at 63 East 107th Street. This area had more immigrant families. It was also just three blocks from Central Park. The three-story building had a ground floor that couldn't be used. The second floor had a large room where two classes met at once. The third floor had a small office and kitchen where the adults gathered.

More children joined the school despite these conditions. By 1914, the school taught 30 children. It had to turn away half of the children who wanted to join. Historian Laurence Veysey says this was because students and teachers shared a lot of warmth and love. Also, new Jewish immigrants, whose families valued education, met Americans who wanted to teach them. Most students came from immigrant families who worked in the garment industry. These families believed in freedom and justice. Like the Association, the early principals of the day school were born in America. Many had degrees from top universities and were not Jewish. They might have been driven by a desire to challenge the usual way of doing things. They also wanted to help poor people and were curious about life in the city's diverse neighborhoods.

The school moved several times and finally closed in 1953.

Students often learned to read later, sometimes at ten or twelve years old.

The Stelton Colony

Choosing the Location

Harry Kelly helped arrange the move to Stelton, New Jersey. This was about 30 miles from New York City. Kelly, a printer and Association member, chose the spot. It was a farm within two miles of a train station. The group bought the land. Then, they sold plots to people who wanted to live in the colony at a fair price. They also set aside land for the school. The colonists believed in freedom. They didn't have one strict rule about property. Plots were owned by individuals. This meant anyone could sell their land and leave the colony whenever they wished. They hoped the colony would become the center of a national movement for free education.

The Stelton Modern School

The school at Stelton opened in 1914. It struggled a bit in its first few years. In 1916, William Thurston Brown became the principal. He had experience running modern schools.

Lessons at Stelton were not forced. The school had no strict rules or set lessons, just like in New York City. Students took part in crafts and outdoor activities. Besides children from the colony families, between 30 and 40 children lived at the school in what used to be a farmhouse. Next to the farmhouse, Stelton built an open-air dormitory. Winters there were cold.

Nellie and James Dick ran the boarding house for children, called the Living House. This couple had opened Ferrer schools in England and other parts of the United States before. They believed in freedom and natural learning. In their dorms, the Dicks taught children to be responsible for themselves.

In 1920, Elizabeth and Alexis Ferm became the co-principals of Stelton. This couple had run schools in New York City before. Their teaching focused on hands-on work and crafts. This included pottery, gardening, carpentry, and dance. These activities took place in the schoolhouse workshops. Students could also study in the library with James Dick. The Ferms left the school in 1925. This was after disagreements with some parents. The parents wanted more focus on reading and social issues. The Ferms did not want to change their teaching style.

The school had a difficult time between 1925 and 1928. Then, the Dicks returned as co-principals. They fixed up the children's dorms, which were in poor condition. They also brought back the children-run newspaper. And they added many activities for adults. The Dicks left in 1933. They wanted to open their own Modern School in Lakewood, New Jersey.

The Ferms were asked to return in the mid-1930s. At this time, fewer children were attending the school. This was because families had less money during the Great Depression. The American government also built a military base next to the colony, which had a negative effect. Elizabeth Ferm died in 1944. Her husband retired four years later. The school had only 15 students at that time. The school closed in 1953.

Legacy

Laurence Veysey described the Ferrer Association as "one of the most notable—though unremembered—attempts to create a different way of life in America." He noted its achievements. These included bringing together college-educated Americans with new Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. It also connected thinkers with workers. Veysey called the Ferrer Modern School one of the few "truly advanced" American progressive schools of the 1920s. The Friends of the Modern School was started in 1973. It became a non-profit organization around 2005. Its goal is to preserve the history of the Stelton Modern School. Former students continued to have regular reunions until the late 2010s. Recordings of these reunions are available at the Rutgers archives. The records of the Friends, and the Modern School itself, can be found at Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers.