Florence Shotridge facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Florence Scundoo Shotridge

|

|

|---|---|

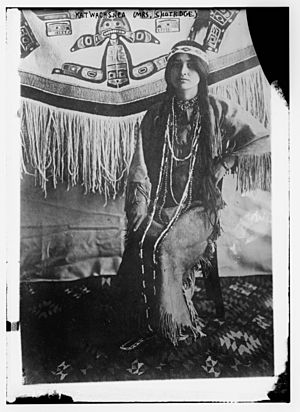

Florence Scundoo Shotridge sitting with her Chilkat blanket.

|

|

| Born | 1882 |

| Died | 1917 (aged 34–35) |

| Occupation | Ethnographer museum educator weaver |

Florence Scundoo Shotridge (1882–1917) was a Native Alaskan Tlingit woman. She was an ethnographer, a museum educator, and a talented weaver. An ethnographer is someone who studies different cultures. From 1911 to 1917, she worked at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, also known as the Penn Museum.

In 1905, Florence showed how to do Chilkat weaving at a big fair called the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon. In 1916, she and her husband, Louis Shotridge, led a trip to southeast Alaska. They collected important cultural items for the Penn Museum. This trip was paid for by John Wanamaker, a rich businessman and museum supporter.

In 1913, Florence and Louis Shotridge wrote an article together called “Indians of the Northwest.” It was published in the University of Pennsylvania's Museum Journal. In the same magazine, Florence Shotridge also wrote her own article. It was called “The Life of a Chilkat Indian Girl.” In this article, she wrote about Tlingit traditions for young girls growing up. She also shared what the Tlingit people expected from women.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Florence Scundoo, whose Tlingit name was Kaatxwaaxsnéi, was born in Haines, Alaska in 1882. Her father was a respected spiritual leader from the Mountain house clan of Chilkat. Her family belonged to the Raven moiety, which is a type of family group. From her mother, Florence learned how to do Chilkat beading and how to weave blankets.

Florence went to the Presbyterian Mission School in Haines for four years. She was very good at singing and playing the piano. She also learned to speak English well there. At this school, Florence met Louis Shotridge. His family was also important in the Chilkat community. Florence's parents had already arranged for her to marry Louis when she was a child. They got married on December 25, 1902.

The town of Haines, where Florence grew up and later died, became bigger during the Klondike Gold Rush in 1896. Haines was in a special place in Alaska. The Chilkat Tlingit people living there could trade between groups from the coast and groups from inland. When Florence was young, many tourists started visiting Haines. They wanted to buy Native Alaskan crafts. The town's economy also depended on fish canneries. These canneries were catching too many salmon.

The U.S. government bought Alaska from Russia in 1867. After that, they banned the Tlingit language and wanted people to speak English. Presbyterian missionaries started working in Haines in 1878. They helped the U.S. government's goals. They tried to spread Christianity and also promoted English education and American customs. This is why Florence, who went to the mission school for four years, learned English so well. Her husband Louis only went for seventeen months, so his English was not as strong.

Showing Chilkat Weaving at a Big Fair

In 1905, the governor of Alaska, John Green Brady, met Florence Shotridge in Haines. He was looking for a Native woman who was skilled in Chilkat weaving. He wanted her to represent Alaska at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon. He also needed someone who could speak English to the visitors at the fair.

Governor Brady chose Florence Shotridge. She was one of the few Chilkat women who could weave and speak English very well. This was because she had gone to the Presbyterian mission school in Haines.

Florence Shotridge went to the fair with her husband Louis. Louis brought several Tlingit crafts to sell to collectors. In Portland, they met George Byron Gordon, who was the director of the Penn Museum. He was planning a trip to Alaska to buy cultural items. The Shotridges got along well with Gordon. He bought 49 Alaskan objects from them for the Penn Museum.

Working at the Museum

After the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition ended, Florence and Louis Shotridge did not have steady jobs. From 1906 to 1913, they took many temporary jobs. They also hired a teacher to help them improve their English. In 1906, they joined Antonio Apache’s Indian Crafts Exhibition in Los Angeles. They also took part in other Indian craft fairs. In 1911, they performed with a traveling Indian opera company. Florence played the piano and Louis sang. They also went to the World in Cincinnati Exposition in 1912.

In 1912, Florence and Louis Shotridge visited New York and then Philadelphia. They stayed with Frank Speck, an anthropologist from the University of Pennsylvania. The Penn Museum director, George Byron Gordon, hired Louis Shotridge for a temporary job. Later, in 1915, he gave Louis a full-time job. Louis became an Assistant Curator and cataloguer for the American section of the Penn Museum.

Florence worked at the museum as a volunteer. She helped Louis with his work. She also led groups of schoolchildren on tours of the museum. She often dressed in Plains (not Northwest) Indian clothing. This was to make the tours more interesting for visitors, who called her the “Indian Princess.” Meanwhile, Louis took classes at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. He wanted to learn business skills that he could use in Alaska.

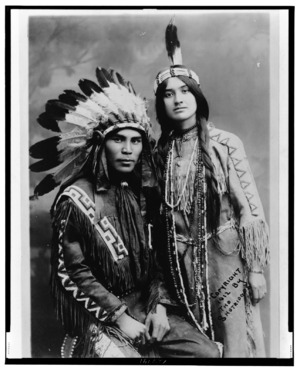

The Penn Museum was trying to reach more people at this time. Florence and Louis Shotridge performed Native American traditions for museum visitors. Photos show that Florence and Louis Shotridge sometimes wore Plains Indian outfits. These outfits had leather, beads, and feathers. They were very different from the Tlingit clothing of Alaska. Florence often led groups of schoolchildren through the museum while dressed in these Native American outfits.

In 1916, Florence and Louis Shotridge went to Alaska for a collecting trip. This trip was paid for by John Wanamaker, a wealthy businessman from Philadelphia. The Shotridge Expedition was the first anthropology trip led by Native Americans. Louis and Florence were trusted to collect cultural objects. They also gathered detailed information about myths and religious beliefs. Florence had been sick with tuberculosis for years. She was very ill during this trip. She eventually died in Haines, Alaska, in a house that the Shotridges had built.

The Chilkat Blanket

Florence Shotridge was a very skilled weaver, beader, and basket maker. She learned traditional Chilkat weaving arts from her mother. In 1905, while living in Haines, Alaska, she met John Green Brady. He was the governor of Alaska from 1897 to 1906. He was looking for Native Alaskans to show the state's cultural traditions at the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon.

Brady asked Florence Shotridge to show Chilkat weaving. She was the only one in her tribe who spoke English. He also invited her husband Louis to describe Tlingit masks and dyes.

At this fair, the Shotridges met George Byron Gordon, the director of the Penn Museum. He later hired Louis in Philadelphia in 1912. Louis Shotridge lived 22 years longer than Florence. He published many articles about Native cultures. He also became the subject of many studies. However, as anthropologist Elizabeth P. Seaton said, “It was in fact Florence’s skill at weaving which started the Shotridges’ connection with the world of anthropological trade.”

Florence Shotridge started weaving a special blanket in Portland. She finished it in Los Angeles at the Indian Crafts Exhibition. She made the blanket from cedar bark and wool. The wool came from five wild mountain goats. The black dye came from the bark of the spruce tree. The bright yellow color came from a yellow moss found only in Alaska. This moss is hard to get, so the dye is rare and expensive. The pattern on the blanket was like her father’s family symbol, or totem.

Later, in an interview with The North American newspaper, she said she spent eight months weaving the blanket. She worked on it for about six hours every day. She also said the blanket was worth $1,500.

In 1911, Louis Shotridge asked the Penn Museum’s director, George Byron Gordon, to buy Florence’s Chilkat blanket. Gordon said no. But in 1914, anthropologist Edward Sapir bought Florence’s blanket instead. Sapir had worked at the Penn Museum until 1910. At that time, Sapir was in charge of the anthropology section at Ottawa’s Victoria Memorial Museum. This museum is now called the Canadian Museum of History. It keeps Florence Shotridge’s blanket, which is called “Chilkat Robe”, Artifact VII-A-131. The same museum also has a description of the blanket, called “The Tina Blanket,” that Florence wrote. In her writing, she described its pictures, which included the grizzly bear symbol of her father’s house.

The Penn Museum does have an unfinished Chilkat blanket that Florence Shotridge started to weave. It is made of wool and cedar bark, and it is from 1912.

Later Life and Impact

By the time Florence and Louis Shotridge went on the Wanamaker-funded trip to Alaska in 1916, Florence Shotridge was very sick. She had been ill with tuberculosis for many years. She died several months later in Haines in 1917. A Philadelphia newspaper wrote an obituary saying, “Minnehaha Is Dead.” They called her by the name of a character from a famous poem.

Filmmaker Pablo Helguera made a video documentary about the Penn Museum in 2010. It was called What in the World. In it, he showed that Florence Shotridge’s work was mostly for people who were not Native American. Helguera said that Florence and her husband Louis were “playing to others’ expectations as to what constitutes Indian-ness.” This means they were acting in ways that fit what non-Native people expected Native Americans to be like.

In 2001, anthropologist Elizabeth Seaton wrote about Florence Shotridge. She said that during her short time at the Penn Museum after 1912, Florence was like a “‘museum Indian’ – a living ethnographic exhibit.” This means she sometimes showed Native American life in a way that fit old ideas about Native Americans. She showed a general idea of Native American life for museum visitors. She also collected Native Alaskan art and cultural items for a museum far away. Because of this, her career as an ethnographer and performer is sometimes seen as complex and even debated.

Images for kids