George Teamoh facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

George Teamoh

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the Virginia Senate from the Norfolk County and Portsmouth district |

|

| In office October 5, 1869 – December 5, 1871 |

|

| Preceded by | George W. Grice |

| Succeeded by | Matthew P. Rue |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1818 Norfolk, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | after 1887 |

| Political party | Republican |

| Occupation |

|

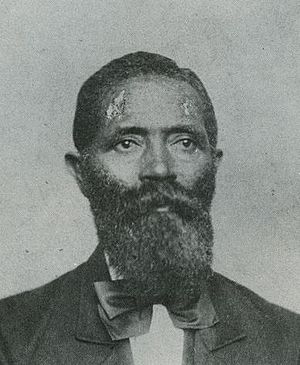

George Teamoh (born 1818 – died after 1887) was an amazing American who was born into slavery in Norfolk, Virginia. He worked in tough conditions at places like the Fort Monroe and the Norfolk Naval Yard before the American Civil War. He bravely escaped to freedom in New York and later moved to Massachusetts around 1853.

After the war, Teamoh returned to Virginia. He became an important community leader. He was part of the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1868. Later, he served in the Virginia Senate during the Reconstruction era. In his later years, he became an author. Teamoh's autobiography is special because he clearly spoke out against the use of enslaved workers by the military. He also criticized the government for allowing slavery and not protecting newly freed Black people.

Teamoh wrote about his experiences: "I have worked in every Department in the Navy Yard and Dry-Dock, as a laborer, and this during very long years of unrequited toil, and the same might be said of the vast numbers, reaching to thousands of slaves who have been worked, lashed and bruised by the United States government ..."

His story also shares important details about Virginia after the Civil War. He was elected to and worked in the state government during Reconstruction. He openly talked about the role of African American delegates at the state convention. He also shared his efforts as a state senator to make work policies fair at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard. He even discussed the disagreements within the Republican party that led to him losing his election.

Contents

George Teamoh's Early Life and Education

George Teamoh was born into slavery in 1818 in Norfolk, Virginia. His owners were Josiah and Jane Thomas. When he was about ten, he moved with the Thomas family to Portsmouth, Virginia. He didn't share much about his parents, but he mentioned his mother's name was Winnie. She died when he was very young.

In 1832, while working in a brickyard, Teamoh taught himself to read and write. He listened to white children and learned by singing the alphabet. He also identified words on posters. Later, he found a dictionary that helped him learn many new words. He loved William Shakespeare's plays and enjoyed going to the theater. He also became very familiar with the Church of England and its Book of Common Prayer.

Teamoh was very proud of his ability to read and write. He wrote "written by himself" on the covers of his autobiography notebooks. His literacy made other Black people ask him to read or write for them. However, it also made many white people uneasy or suspicious.

Working as an Enslaved Person

From the 1830s to the 1840s, George Teamoh's owner, Jane Thomas, hired him out. He worked as a laborer, caulker, and ship-carpenter. He worked at the Norfolk Navy Yard, Fort Monroe, and for private businesses. By the 1830s, the Norfolk Navy Yard (then called Gosport Navy Yard) needed skilled ship caulkers. Caulking was hard and dirty work. It involved sealing the seams of ships to make them waterproof. This job was often done by enslaved or free Black people.

When Teamoh first started at the shipyard, white workers were not happy about enslaved labor. They worried that free Black people might encourage enslaved people to rebel. Despite the difficulties, Teamoh learned his trade well. He worked with a master ship caulker named Peter Teabo. Teamoh was paid about $1.62 a day, while white caulkers usually got $2 a day. Even so, Teamoh was able to save some money.

The Navy Department tried to stop the practice of white mechanics renting out their enslaved workers. However, enslaved labor continued at the Norfolk Navy Yard. The atmosphere there was often tense. Sometimes, enslaved workers were listed as "Ordinary Seamen" on the shipyard's employment lists. This was a trick to hide that they were enslaved. Teamoh himself was listed this way. He worked on the ship USS Constitution for about two years. He even received a discharge paper in 1845. But Teamoh knew it was just a way to keep using enslaved labor.

Family Life and Escape to Freedom

In 1841, George Teamoh married an enslaved woman named Sallie. They had at least one son, John, and two daughters, Jane (also called Lavinia) and Josephine. In 1853, Sallie and their children were sold to a slave dealer. This happened despite Teamoh's pleas. Sallie was eventually bought by someone in Richmond, Virginia.

In 1853, Jane Thomas had promised to free Teamoh someday. However, Virginia's laws made it hard and costly to free enslaved people. So, Jane Thomas helped Teamoh by listing him as a carpenter on a merchant ship called Currituck. The ship was going to Bremen, Germany. On the way back, Teamoh decided to escape in New York City. He hired a lawyer to get his back pay and declared himself free. Then, he moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts around December 1853.

As a runaway and a free man, Teamoh got some help from people involved with the Underground Railroad. However, he soon found that life as a free man was still very hard. New Bedford had many other runaways also looking for work. He found work as a caulker for a short time. But during a tough winter, he was laid off. The competition for jobs was high. He ended up shoveling snow and loading coal without proper winter clothes. Because of this, he moved to Boston, Massachusetts. There, he found work with his half-brothers, John William and Thomas.

A Leader in Politics

After Union soldiers took control of Portsmouth in 1862, Teamoh returned to work at the shipyard. He quickly became an important leader in the African American community in Portsmouth. He fought for fair wages for his fellow shipyard workers. He was also able to find his wife Sallie and daughter Josephine.

After reuniting with his family, Teamoh quickly got involved in state politics. He became a delegate at the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1868. This was a meeting to write a new state constitution after the Civil War. Then, he served one term as a state senator from 1869 to 1871.

In January 1871, Teamoh spoke in favor of a bill to stop whipping as a punishment. He pointed out that many formerly enslaved people like himself had suffered from such punishments. He worked hard to make sure that workers at the Norfolk Navy Yard received fair pay and work hours. Teamoh and other representatives helped secure an eight-hour workday. However, the Navy Department cut wages by 20%, saying that fewer hours meant less pay. President Ulysses S. Grant had to step in. He ordered that government workers' wages should not be cut because of reduced hours. The eight-hour workday for federal workers began in 1868.

Later Life and Legacy

George Teamoh saw the end of the Reconstruction era government. He also lost his home because of a bad loan. He blamed a trust company and a local minister for this. The end of Reconstruction was a big blow. This was when Southern Democrats, called "Redeemers," regained power. They opposed Black people's right to vote and reversed much of the progress made. By 1877, U.S. Army troops left the South. This ended Reconstruction and removed protection for newly freed Black people.

In his last two decades, Teamoh focused on writing and improving his autobiography. He said he wrote it because many friends asked him to. His book was finally published in 1990, with help from his family.

George Teamoh died sometime after 1887. The exact time or place is not known. His name last appeared on local tax records in 1887. His wife Sallie died on September 2, 1892.

See also

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |