Georges Simenon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Georges Simenon

|

|

|---|---|

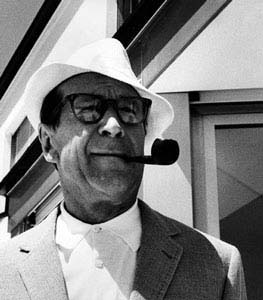

Simenon in 1963

|

|

| Born | Georges Joseph Christian Simenon 12 February 1903 Liège, Wallonia, Belgium |

| Died | 4 September 1989 (aged 86) Lausanne, Romandy, Switzerland |

| Pen name | G. Sim, Monsieur Le Coq |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Language | French |

| Nationality | Belgian |

| Alma mater | Collège Saint-Louis, Liège |

| Years active | 1919–1981 |

| Notable awards | Académie royale de Belgique (1952) |

Georges Joseph Christian Simenon (12/13 February 1903 – 4 September 1989) was a famous Belgian writer. He is best known for creating the fictional detective Jules Maigret. Simenon was one of the most popular authors of the 20th century. He wrote about 400 novels, 21 books of memories, and many short stories. His books sold over 500 million copies worldwide!

Besides his detective stories, he also wrote serious novels he called romans durs (hard novels). Many famous writers, like André Gide, admired his work. Gide even said, "I consider Simenon a great novelist, perhaps the greatest, and the most genuine novelist that we have had in contemporary French literature."

Simenon was born and grew up in Liège, Belgium. He lived in France for many years (1922–1945), then in the United States (1946–1955), and finally in Switzerland (1957–1989). Many of his stories were inspired by his own life. This included his childhood in Liège, his travels, and his experiences during wartime.

Critics like John Banville have praised Simenon's novels. They liked how he showed deep understanding of people's thoughts and feelings. They also admired how he brought different times and places to life in his stories. Some of his most famous books include The Saint-Fiacre Affair (1932) and The Cat (1967).

Contents

Early Life and School

Georges Simenon was born at 26 Rue Léopold (now number 24) in Liège. His parents were Désiré Simenon and Henriette Brüll. His father worked in an accounting office for an insurance company. Georges was born either late on February 12, 1903, or just after midnight on February 13. The date on his birth certificate might have been changed due to old superstitions.

The Simenon family had roots in Walloon and Flemish areas of Belgium. His mother's family had Flemish, Dutch, and German ancestors. One of his mother's ancestors was Gabriel Brühl, who lived in Limburg in the 1700s. Simenon later used Brühl as one of his many pen names.

In 1905, when Georges was two, his family moved to 3 rue Pasteur (now 25 rue Georges Simenon) in Liège. His brother Christian was born in 1906. Simenon felt that his mother preferred Christian, which made him feel a bit jealous. However, young Simenon looked up to his father. He later said that he partly based Inspector Maigret's personality on his dad.

Georges learned to read at age three at the Ecole Guardienne. From 1908 to 1914, he went to the Institut Saint-André.

In 1911, the Simenons moved to 53 rue de la Loi. Here, they rented rooms to students from Eastern Europe, including Jewish people and political refugees. This gave young Simenon a chance to learn about different cultures and the wider world. These experiences later appeared in his novels, like Pedigree (1948) and Le Locataire (The Lodger) (1938).

When World War I started in August 1914, the German army occupied Liège. Simenon's mother took in German officers as lodgers, which his father did not like. Simenon later said that the war years were some of the happiest times of his life. He also remembered that "my father cheated, my mother cheated, everyone cheated."

In October 1914, Simenon began studying at the Collège Saint-Louis, a Jesuit high school. After a year, he moved to Collège St Servais, where he studied for three years. He was very good at French but his grades in other subjects dropped. He read many classic books from Russia, France, and England. He often skipped school and sometimes took small things to buy treats.

In 1917, the Simenon family moved to a former post office building. Simenon left school in June 1918, before his final exams, using his father's heart condition as an excuse. After working briefly in a bakery and a bookshop, Simenon was unemployed when the war ended in November 1918. He saw difficult scenes in Liège as people accused of helping the Germans were punished. These events stayed with him and he wrote about them in Pedigree.

Early Career as a Writer (1919–1922)

In January 1919, 15-year-old Simenon started working as a junior reporter for the Gazette de Liège. This was a Catholic newspaper. Within a few months, he was promoted to crime reporting, signing his articles "Georges Sim." By April, he had his own opinion column, signed "Monsieur Le Coq." He also interviewed important people like Hirohito, the Crown Prince of Japan. In 1920-1921, he took a course on forensic science at the University of Liège to learn more about police methods.

In May 1920, Simenon began publishing short stories in the Gazette. In September, he finished his first novel, Au Pont des Arches, which he published himself in 1921. He wrote two other novels while at the Gazette, but these were never published.

In June 1919, Simenon joined a group of young artists called "Le Caque." They met at night to talk about art and ideas. In early 1922, a member of the group, Joseph Kleine, died. Simenon was deeply affected by his death.

Through "Le Caque, " Simenon met Régine Renchon, a young painter. They started a relationship in early 1921 and soon got engaged. They decided Simenon should finish his military service before they married.

Simenon's father passed away in November 1921. Simenon called this "the most important day in a man's life." Soon after, he began his military service. After a short time in Germany, he was moved to Liège and was allowed to keep writing for the Gazette.

When Simenon's military service ended in December 1922, he left the Gazette. He moved to Paris to prepare a home for himself and Régine, whom he called "Tigy."

Life in France (1922–1945)

Learning to Write (1922–1928)

In Paris, Simenon found a small job with a political group. In March 1923, he went back to Liège to marry Régine. Even though neither of them was very religious, they married in a Catholic church to please Simenon's mother.

The newlyweds moved to Paris. Régine tried to become a painter, while Simenon continued to work and write articles for magazines. He also wrote short stories for popular magazines, but he didn't sell them very often.

In the summer of 1923, Simenon became a private secretary for the Marquis de Tracy. This meant he spent nine months a year at the Marquis's country homes. Régine soon moved to a village near the Marquis's main estate.

While working for the Marquis, Simenon started sending stories to Le Matin newspaper. The editor, Colette, told him to make his writing "less literary." Simenon understood this to mean he should use simple descriptions and common words. He followed her advice and quickly became a regular writer for the paper.

With a steady income from his writing, Simenon left the Marquis's job in 1924. He and Régine found an apartment in Paris. Simenon was writing and selling short stories very quickly, sometimes 80 typed pages a day. He then started writing popular novels. His first, Le roman d'une dactylo (The Story of a Typist), sold quickly. From 1921 to 1934, he used 17 different pen names and wrote 358 novels and short stories.

In the summer of 1925, the Simenons met Henriette Liberge, an 18-year-old, during a holiday in Normandy. Régine offered her a job as their housekeeper in Paris, and Henriette accepted. Simenon called her "Boule," and she became a part of their household for the next 39 years.

The Simenons grew tired of their busy life in Paris. In April 1928, they set off with Boule on a six-month trip through the rivers and canals of France in a small boat called the Ginette. Simenon's writing increased, and he published 44 popular novels in 1928.

Maigret's Debut and Break (1929–1939)

In spring 1929, the Simenons and Boule traveled through northern France, Belgium, and Holland in a larger, custom-built boat, the Ostrogoth. Simenon had started writing detective stories for a new magazine called Détective. He also continued to publish popular novels.

During this northern trip, Simenon wrote three popular novels featuring a police inspector named Maigret. Simenon began working on one of these novels in September 1929, while the Ostrogoth was being repaired in the Dutch city of Delfzijl. This city is now known as the birthplace of Simenon's most famous character.

When he returned to Paris in April 1930, Simenon finished Pietr-le-Letton. This was the first novel where Commissioner Maigret of the Paris crime brigade was a fully developed character. The novel was published in parts in a magazine later that year. It was the first time Simenon used his real name for a fictional work.

The first Maigret novels were launched as books in February 1931 at a special party with a police and criminals theme. The party was widely reported, and the novels received good reviews. Simenon wrote 19 Maigret novels by the end of 1933. The series eventually sold 500 million copies.

In April 1932, the Simenons and Boule moved to La Rochelle in southwest France. Soon after, they went to Africa, where Simenon visited his brother. Simenon also visited other places in Africa and wrote articles that were critical of colonialism. He used his African experiences in novels like Le Coup de Lune (Tropic Moon) (1933).

In 1933, the Simenons visited Germany and Eastern Europe. Simenon also interviewed Leon Trotsky in Turkey. When he returned, he announced he would not write any more Maigret novels. He signed a contract with the well-known publisher Gallimard for his new work.

Maigret, written in June 1933, was meant to be the last book in the series. It ended with the detective retiring. Simenon called the Maigret novels "semi-literary" and wanted to be seen as a serious writer. He aimed to win the Nobel Prize for Literature by 1947.

Simenon's important novels from the 1930s, written after Maigret's temporary retirement, include L'homme qui regardait passer les trains (The Man who Watched the Trains Go By) (1938). André Gide and François Mauriac were among his biggest fans at this time.

In 1935, the Simenons went on a world tour. They visited the Americas, the Galapagos Islands, Tahiti, Australia, and India. Then they moved back to Paris, where they lived a very comfortable life.

They moved back to La Rochelle in 1938. In April of the next year, Simenon's first child, Marc, was born.

World War II (1939–1945)

Simenon was in a café in La Rochelle when France declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939. In May 1940, Germany invaded Belgium, and La Rochelle became a place for Belgian refugees. The Belgian government made Simenon the Commissioner for Refugees. He helped organize housing, food, and health care for about 55,000 war refugees. By August, all Belgian refugees had returned home, and Simenon went back to his normal life.

Later in 1940, a doctor told Simenon he had a serious heart problem. Simenon started writing his memories, Je me souviens (I remember), as a letter to his son. Later, another doctor said his heart was fine.

Simenon started writing Maigret stories and novels again, completing two in 1940 and three in 1941. He also wrote longer novels like Pedigree. Since he was a popular author who was not Jewish and avoided war themes, he had few problems getting his books published during a time of censorship.

Some of his major works written during the war years include La veuve Couderc (The Widow Couderc) (1942). Simenon also wrote letters to other writers, like André Gide.

During the war, Simenon sold the film rights for five of his novels to Continental Films. This company was funded by the German government and did not allow Jewish people to work there. One film based on Simenon's Les inconnus dans la maison (Strangers in the House) had strong anti-Semitic themes that were not in the book. Underground newspapers started criticizing Continental Films and anyone who worked with them.

In 1942, a French government office told Simenon they thought he might be Jewish. They gave him one month to prove he wasn't. Simenon was able to get the necessary birth and baptism certificates through his mother. Soon after, the Simenons moved to a more isolated village.

In November 1944, after the Germans left, Simenon, Marc, and Boule moved to a hotel. Régine went back to their house near La Rochelle. In January 1945, Simenon was placed under house arrest by the police because they suspected he had helped the Germans. After three months of investigation, he was cleared of all charges.

Simenon went to Paris in May 1945. He decided to move to America. The rest of his family soon joined him in Paris. Simenon used his connections to get the travel documents for America. However, Régine said she would only go to America with Marc if Boule stayed in France. Simenon agreed to Régine's request.

United States and Canada (1945–1955)

The Simenons arrived in New York in October 1945. They soon moved to Canada, settling in Ste-Marguerite du Lac Masson. In November, Simenon met Denyse Ouimet, a 25-year-old French-Canadian, and hired her as his secretary. Denyse moved into the Simenon home in January 1946. Simenon wrote about his experiences with Denyse in his novels Trois chambres à Manhattan (Three Bedrooms in Manhattan) (1947) and Lettre à mon juge (Act of Passion) (1947).

The Simenons and Denyse drove to Florida in the summer of 1946. Then they visited Cuba to arrange for permanent visas for the United States. Simenon wrote Lettre à mon juge in Florida, which is considered one of his important works.

In June 1947, the Simenons moved to Arizona. Boule joined them there in 1948. Simenon continued to write quickly, working from 6 am to 9 am daily, and writing about 4,500 words a day. In Arizona, Simenon wrote two Maigret novels and several romans durs (hard novels). These included La neige était sale (The Snow Was Dirty) (1948), another major work. The 1951 American paperback edition of this novel sold 2 million copies.

Denyse became pregnant in early 1949, and Simenon asked Régine for a divorce. Denyse gave birth to Jean Dennis Chrétien Simenon (known as John) on September 29. Régine had moved to California with Marc and Boule. Simenon, Denyse, and the baby soon moved to Carmel-by-the-Sea to be close to Marc. The divorce was finalized in Nevada on June 21, 1950. Simenon married Denyse the next day.

The newlyweds moved to Lakeville, Connecticut. They also rented a house nearby for Régine, Marc, and Boule. In the five years he lived in Connecticut, Simenon wrote 13 Maigret novels and 14 romans durs. These included important works like La mort de Belle (Belle) (1952) and L'horloger d'Everton (The Watchmaker of Everton) (1954).

While living in Connecticut, Simenon's book sales grew to an estimated 3 million a year. He was also elected president of the Mystery Writers of America. Simenon and Denyse visited Europe twice, in 1952 and 1954. On the 1952 trip, Simenon became a member of the Royal Belgian Academy. In February 1953, Denyse gave birth to a daughter, Marie-Georges Simenon (known as Marie-Jo). By this time, Boule had moved in with Denyse and Simenon.

By 1955, Simenon felt disappointed with America. Denyse wanted to live in Europe and seemed to be growing distant from him. In March, Simenon, Denyse, and Boule left for a European holiday and never returned to live in America.

Return to Europe (1955–1989)

The Simenons settled in France at Mougins, near Cannes. Régine and Marc lived in a hotel nearby. Simenon wrote two Maigret novels and two romans durs during his first six months on the French Riviera. He was still looking for a permanent home. In July 1957, the Simenons and Boule moved to the Château d'Echandens near Lausanne, Switzerland. They stayed there for seven years.

In May 1959, Denyse gave birth to a son, Pierre. He became very ill but survived his difficult first year. In December 1961, Simenon and Denyse hired Teresa Sburelin, a young Italian woman, as a maid. Teresa soon became Simenon's companion and stayed with him for the rest of his life.

Simenon continued to write three to five novels a year at Enchandens. These included two of his most notable works, Le président (The Premier) (1958) and Les anneaux de Bicêtre (The Patient) (1963).

However, the relationship between Denyse and Simenon was getting worse. In June 1962, Denyse went to a mental health clinic for several months. In 1961, the Simenons had decided to build a new house in Epalinges, above Lausanne. The house was finished in December 1963, but Denyse only lived there for a few months before returning to the clinic.

Denyse left Epalinges for the last time in April 1964. In November, Simenon let Boule go, and she went to live with Marc, who was now married with children.

Although Simenon never divorced Denyse, he was now living with his companion Teresa and three of his children: John, Marie-Jo, and Pierre. He continued to work steadily, completing three to four books a year from 1965 to 1971. These included important works like Le petit saint (The Little Saint) (1965) and Le chat (The Cat) (1967).

In February 1973, Simenon announced that he was retiring from writing. A few months later, he and Teresa moved into a small house in Lausanne. He did not write any new fiction after that, but he dictated 21 books of his memories.

In May 1978, Simenon's daughter, Marie-Jo, passed away in Paris at the age of 25. In his last book of memories, Mémoires intimes (Intimate memoirs) (1981), he wrote, "One never recovers from the loss of a daughter one has cherished. It leaves a void that nothing can fill."

Simenon had a brain operation in 1984 but recovered fully. From late 1988, he used a wheelchair. He died on September 4, 1989, after a fall.

Honors and Legacy

- President of the Mystery Writers of America (1952)

- Member of Royal Academy of French Language and Literature of Belgium (1952)

- Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur (1955) - a high honor in France

- Honorary Member of American Academy of Arts and Letters (1971)

In 2003, a special collection called La Pléiade published 21 of Simenon's novels in two volumes. These novels were chosen by experts from the Centre for Georges Simenon Studies at the Université de Liège. A third volume of 8 novels and two autobiographical works was published in 2009.

Film Adaptations

Many of Simenon's works have been made into movies and television shows. He is credited on at least 171 productions. Some notable films include:

- Night at the Crossroads (France, 1932), starring Pierre Renoir as Maigret

- The Strangers in the House (France, 1942)

- Panic (France, 1946)

- The Man on the Eiffel Tower (1949), starring Charles Laughton as Maigret

- The Man Who Watched Trains Go By (UK, 1952)

- Maigret Sets a Trap (France, 1958), starring Jean Gabin as Maigret

- Maigret (UK, TV series, 1960–1963), starring Rupert Davies as Maigret

- Le chat (France, 1971)

- The Widow Couderc (France, 1971)

- The Clockmaker (France, 1974)

- Monsieur Hire (France, 1989)

- Maigret (France, TV series, 1991–2005), starring Bruno Cremer as Maigret

- Maigret (UK, TV series, since 2016), starring Rowan Atkinson as Maigret

- Maigret (France, 2022), featuring Gérard Dépardieu as Maigret

Stage Adaptations

- The Red Barn, a play based on the novel La Main (English title The Man on the Bench in the Barn). It was directed by Robert Icke at the Lyttelton Theatre, London, in October 2016.

See also

In Spanish: Georges Simenon para niños

In Spanish: Georges Simenon para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |