German phosgene attack (19 December 1915) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids German phosgene attack (19 December 1915) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Local operations December 1915 – June 1916 Western Front, in the First World War | |||||||

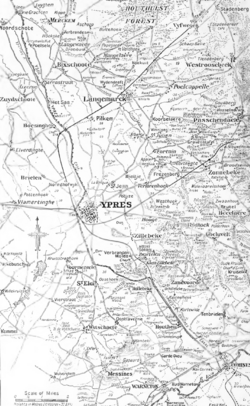

Map of the Ypres district |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Erich von Falkenhayn | Douglas Haig | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Elements of 2 corps specialist Pioneer regiment |

2 divisions | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Gas: 1,069 | |||||||

On 19 December 1915, the German army launched its first attack using a deadly new gas called phosgene against British soldiers. This attack happened near Wieltje, a town north-east of Ypres in Belgium. It was part of the fighting on the Western Front during the First World War.

Earlier in 1915, Germany had already used chlorine gas. This happened on 22 April 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres. The surprise gas attack helped the Germans capture a lot of land around Ypres. However, the effectiveness of gas as a weapon soon decreased. This was because French and British troops quickly developed ways to protect themselves, like special helmets.

German scientists then looked into adding phosgene to chlorine. Phosgene was much more dangerous. This new gas mix was first used in May 1915 against French and Russian troops. In December 1915, the German 4th Army used this mix against British troops in Belgium. The British had actually captured a German soldier who told them about the plan. This warning helped them prepare.

During the attack, German raiding parties tried to cross no-man's land (the area between enemy trenches). But British soldiers fought them off with small-arms fire. The British had taken steps to prevent panic. Even though their gas helmets were not fully designed for phosgene, their preparations helped. Only one British division, the 49th (West Riding) Division, had many gas casualties. This happened because some soldiers in the back lines did not get the warning in time. In total, 1,069 British soldiers were affected by the gas, and 120 of them died. After this attack, the Germans realized that gas alone could not win a battle.

Contents

Why Gas Was Used in World War I

Early Chlorine Gas Attacks

On the evening of 22 April 1915, German soldiers released chlorine gas from cylinders. These cylinders were placed in trenches at the Ypres Salient. The gas cloud floated into the positions of French and Algerian soldiers. Many of these troops ran away from the deadly cloud. This created a gap in the Allied lines. If the Germans had pushed forward more, they might have captured Ypres. However, the German attack was meant to distract the enemy, not to break through. They did not have enough soldiers ready to follow up on their success. When German troops tried to move into areas not affected by the gas, Allied guns stopped them.

The gas attack was a big surprise for the French. They had no protection against it. The gas also had a strong psychological effect. Bullets and shells followed a clear path, but gas was different. It changed speed and spread in unpredictable ways. Soldiers could hide from bullets, but gas would follow them. It seeped into trenches and dugouts, slowly choking people. One British soldier described it as "asphyxiating horror." He said men were "struggling for air as if they were drowning."

British scientists quickly identified the gas as chlorine. By the first week of May, they had developed an anti-gas helmet. This helmet was a flannel bag soaked in special chemicals. It was called the British Smoke Helmet. By July, all British troops in France had one. An improved helmet, the P Helmet, came out in November.

The Deadlier Mix: Chlorine and Phosgene

Scientists like Fritz Haber studied how to use chlorine as a weapon. Later, the Nernst–Duisberg Commission looked into adding phosgene to chlorine gas. This would make the gas much more lethal, meaning it could kill more people. Another scientist, Richard Willstätter, helped supply the German army with protective gear. This allowed them to use the deadlier phosgene mix without risking their own soldiers.

The German army started using phosgene from May 1915. They used it on the Western Front against French troops. They also used it on the Eastern Front against Russian soldiers. In one attack, 12,000 cylinders of gas were released. This gas was 95 percent chlorine and 5 percent phosgene. The attack did not stop all Russian artillery. The Germans thought the attack was not very effective. But the Russians suffered 8,394 casualties, with 1,011 deaths.

The first attack on British troops with this new gas mix was planned for 19 December. It was to happen near Wieltje in Belgium. In late 1915, the German army high command approved the plan. A special Gas Pioneer regiment was sent to help. This was the first time the chlorine and phosgene mix would be used against British troops. Phosgene was much deadlier than chlorine.

A German general named Richard von Schubert did not like the plan. He worried that if the attack worked, the front line would move into very muddy ground just before winter. He wanted to attack near Wieltje with Ypres as the main goal. But there were not enough resources for such a big attack. By mid-November, the plan was to place gas cylinders along the front lines of two German army corps.

Getting Ready for the Attack

German Plans and Preparations

Gas cylinders filled with the chlorine and phosgene mix were placed along the German front lines. Because the trenches were not straight, it was hard to place the cylinders in a continuous line. The Germans planned to fire artillery shells, but no big infantry attack would follow. After releasing the gas, small German patrols would go out. Their job was to see how the gas affected the enemy. They also hoped to capture British prisoners and equipment.

British Anti-Gas Measures

After the chlorine gas attacks earlier in 1915, strict rules were put in place. An officer in each army corps watched the wind direction. If the wind was right for a gas release, a "Gas Alert" was given. A guard was placed near every alarm horn or gong. This was done at every dugout and signal office. Gas helmets and alarms were checked every twelve hours. All soldiers wore their helmets ready to put on quickly. Special oil was given for weapons in the front lines.

December 1915 Warnings

On the night of 4/5 December, a German non-commissioned officer was captured near Ypres. He told the British that gas cylinders had been buried along the German front. He also said a gas attack had recently been delayed. Other information suggested a gas attack would happen after 10 December if the weather was good. The British also learned that a German division had arrived from the Eastern Front.

A special warning was sent out to British troops. From 15 December, when the wind was good for a gas attack, the "Gas Alert" was issued. British artillery fired shells at the German lines. They hoped to destroy the gas cylinders. But there was a shortage of ammunition. Each howitzer could only fire about three shells per day. The shelling damaged the German trenches but did not destroy the gas cylinders. The British shelling was still going on when the gas attack began.

The Gas Attack on 19 December

At 5:00 a.m., a strange flare rose from the German lines. At 5:15 a.m., red rockets went up along the German front. British guards immediately gave the alarm. Soon after, a hissing sound was heard, and a strange smell filled the air. In some areas, the space between the enemy trenches was only 20 yards wide. German soldiers fired their rifles before the gas was released. In other areas, the trenches were about 300 yards apart. Rifle fire started with the gas release and increased after fifteen minutes.

Sentries sounded the gas warning with gongs and klaxons. Soldiers quickly manned the trench walls. Some battalions fired their rifles and machine guns, while others waited. British artillery began firing shrapnel shells. No large German infantry attack followed. However, many German soldiers were seen on their trench walls. A British aircraft flying low overhead also faced heavy rifle fire.

Only small groups of German soldiers advanced. In one place, about twelve men moved forward. In another, about 30 soldiers attacked. One group reached the British trench wall before being stopped. The rest were shot down in no-man's land. In one area, German shrapnel shelling made defenders think no infantry attack was coming, so they took cover. Tear gas and high explosive shells were fired at British positions and roads. But no systematic wire-cutting was seen. Heavy German howitzers also shelled towns behind the British lines. The British brought up their reserve troops to prepare for a possible attack.

The German gas release was followed by twenty small raiding parties. They were supposed to observe the gas effects and capture prisoners or equipment. German reports said only two patrols reached the British lines. Several parties suffered many losses from British return-fire. The gas formed a white cloud about 50 feet high. It lasted for thirty minutes before the wind blew it away. The gas spread over a large area, about 8 miles behind the front lines. The gas cloud traveled for about 10 miles, almost reaching the town of Bailleul. Around 6:15 a.m., green rockets were fired from the German front. Then, the British lines were shelled with gas shells. These shells moved quietly and exploded with a "dull splash." In one British division, some soldiers in support trenches were asleep. They were gassed before they could wake up. But most soldiers managed to put on their helmets in time.

On 20 December, a German observation balloon and several airplanes flew over the front lines. After the gas shelling, German artillery returned to firing high explosive shells. The shelling continued on and off until the evening of 21 December.

What Happened Next

Casualties and Effects

A British study found that 1,069 soldiers were affected by the gas. Of these, 120 died. Most of the casualties (75 percent) were from the 49th (West Riding) Division. Food exposed to the gas became tainted, and soldiers who ate it vomited. Some gassed men died suddenly about twelve hours later, especially if they exerted themselves. This happened even if they had shown few signs of illness before.

Later Gas Attacks

The next major German gas attacks against the British happened from 27 to 29 April 1916. These attacks were near the German-held village of Hulluch. During the first attack on 27 April, the gas cloud and artillery fire were followed by raiding parties. These parties briefly entered the British lines. Two days later, a second gas attack happened at Hulluch. This time, the wind changed direction. It blew the gas cloud back over the German lines. This caused many German casualties. British troops also fired at the German soldiers as they ran in the open. The mix of chlorine and phosgene was strong enough to get through the British PH helmet.

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |