Harwell computer facts for kids

The Harwell Dekatron computer

|

|

| Also known as | Wolverhampton Instrument for Teaching Computing from Harwell (WITCH) |

|---|---|

| Developer | Atomic Energy Research Establishment in Harwell, Berkshire |

| Release date | May 1952 |

| Discontinued | 1973 |

| Power | 1.5 kW |

| CPU | Relays for sequence control and valve-based (vacuum tube) electronics for calculations |

| Memory | 20 (later 40) eight-digit dekatron registers |

| Storage | Paper tape |

| Display | Either a Creed teleprinter or a paper tape punch |

| Weight | 2.5 tonnes |

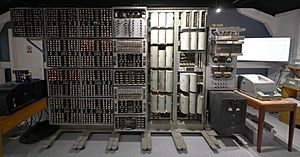

The Harwell computer, also called the Harwell Dekatron computer, was an early British computer from the 1950s. It was later known as the Wolverhampton Instrument for Teaching Computing from Harwell (WITCH). This amazing machine used old-fashioned electronic parts like valves (like light bulbs) and relays (electronic switches).

From 2009 to 2012, experts carefully rebuilt the computer at the The National Museum of Computing. In 2013, the Guinness Book of World Records officially named it the world's oldest working digital computer. It had held this title before, until it stopped working in 1973. Today, the museum uses the Harwell computer to teach students about how computers work. Its special dekatron tubes light up, showing how it stores information.

Contents

Building the Harwell Computer

This huge computer weighs 2.5 metric tons (2.8 short tons), which is about the same as two cars! It was built at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment in Harwell, England. Work on the computer began in 1949. It started running in April 1951 and was used until 1957.

How the Harwell Computer Worked

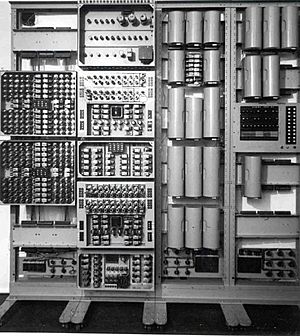

The Harwell computer used 828 dekatrons. These were special glass tubes that stored information, much like RAM in computers today. It also used paper tape to put in information and store programs. The machine had 480 relays to control its steps and 199 valves to do calculations.

The computer was very big, standing 2 meters (about 6.5 feet) tall, 6 meters (about 20 feet) wide, and 1 meter (about 3 feet) deep. It used a lot of electricity, about 1.5 kilowatts. It showed its answers on a Creed teleprinter (like an old typewriter) or by punching holes in paper tape.

This computer worked with numbers in a decimal system (like we do, using base 10). It could store 20 numbers, each with eight digits. Later, this was increased to 40 numbers. These parts were often found in British telephone exchanges.

A Slow but Reliable Machine

Compared to today's computers, the Harwell computer was very slow. It took 5 to 10 seconds just to multiply two numbers! But it was incredibly reliable. One of its designers, Ted Cooke-Yarborough, said a slow computer needed to run for a long time without needing help.

From May 1952 to February 1953, it ran for an average of 80 hours every week. Dr. Jack Howlett, who was in charge of the computer lab, said it could be left alone for long periods. He remembered one Christmas holiday when it ran by itself for over ten days!

The computer's main strength was its ability to work tirelessly. Human mathematicians, called "hand-computers," could calculate at a similar speed. But they couldn't keep going for as long as the machine. Dr. Howlett told a story about a hand-computer named Bart Fossey. Bart tried to race the machine with his own calculator. He kept up for about half an hour but then got tired. The machine, however, just kept going.

The WITCH Computer

In 1957, the Harwell computer was no longer needed at Harwell. The Oxford Mathematical Institute held a competition. They wanted to give the computer to the college that could show the best plan for its future use.

The Wolverhampton and Staffordshire Technical College won the competition. This college later became Wolverhampton University. The computer was used there to teach computing until 1973. At this time, it was given a new name: the WITCH, which stood for the Wolverhampton Instrument for Teaching Computing from Harwell.

After its time at the college, the WITCH computer was given to the Museum of Science and Industry, Birmingham in 1973. When that museum closed in 1997, the computer was taken apart and stored safely.

Bringing the WITCH Back to Life

In September 2009, the WITCH computer was moved to The National Museum of Computing. This museum is located at Bletchley Park, a famous historical site. A group called the Computer Conservation Society started a project to restore the computer.

The museum, which is a charity, asked people and companies to help pay for the restoration. They could buy one of 25 "shares" for £4,500 each. In 2012, the restoration was finished, and the computer was working again!

See also

- List of vacuum-tube computers

- Electromechanical computer

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |