History of Buganda facts for kids

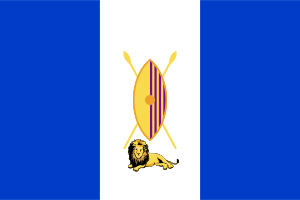

The history of Buganda tells the story of the Buganda kingdom and its people, the Baganda, who are the largest traditional kingdom in what is now Uganda.

Contents

Buganda's Early Days and Growth

The Buganda kingdom is likely much older than people once thought. It started as a small area north of Lake Victoria.

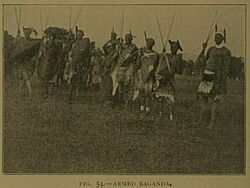

Buganda quickly became very powerful in the 1700s and 1800s. It grew into the strongest kingdom in the region. From the 1840s, Buganda began to expand. They used large groups of war canoes to control Lake Victoria and the lands around it. By taking control of other groups, Buganda became a strong "empire in the making."

First European Visitors

The first time Europeans directly met the Baganda was in 1862. British explorers John Hanning Speke and Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton visited Buganda. They wrote that the kingdom was very well organized.

Muteesa I of Buganda, who was the king (called a Kabaka), met explorers like John Hanning Speke and Henry Morton Stanley. He invited missionaries from the Church Missionary Society to Buganda. One of these missionaries was Alexander Murdoch Mackay. Even though many tried, Muteesa I never changed his religion.

In 1884, Muteesa I died, and his son Mwanga II became the new Kabaka. Mwanga II was removed from power several times but always came back. In 1892, Mwanga signed a treaty with Captain Lord Lugard. This agreement made Buganda a protectorate under the British East Africa Company. The British saw Buganda as a very important place.

How Buganda Became Strong

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Kabakas of Buganda gained more power. They did this by removing rivals and changing old rules about who could be in charge. They also collected more taxes from their people. Buganda's armies also took land from their neighbor, Bunyoro.

The Baganda had a special way of making sure the king's family didn't become too powerful. Children of the Kabaka belonged to their mother's family group, not a royal family group. This also meant the Kabaka could marry into any family in society.

One of the most important advisors to the Kabaka was the Katikkiro. This person was like a prime minister and chief judge. The Katikkiro and other powerful ministers helped the Kabaka make decisions. By the late 1800s, the Kabaka had replaced many traditional family leaders with his own chosen officials. He even called himself the "head of all the clans."

The British were very impressed by Buganda's organized government. Because of this, Buganda became the most important part of the new British protectorate. Many Baganda people got good opportunities in schools and businesses. Baganda officials also helped the British govern other groups in Uganda. This is why much of Uganda's early history was written from the viewpoint of the Baganda and the British. By the time Uganda became independent in 1962, Buganda had the best living standards and the highest number of people who could read and write.

Politics Before Uganda's Independence

As Uganda got ready for independence, many new political parties started. This worried the old leaders in the Ugandan kingdoms. They knew that power would shift to the national government.

A speech in 1953 caused a lot of anger. The British official in charge of colonies talked about possibly joining Kenya, Uganda, and Tanganyika into one big group, like a federation. Many Ugandans knew about the federation in central Africa, where white settlers had a lot of power. Ugandans were very afraid that white settlers in Kenya would control an East African federation. Kenya was also going through a difficult time with the Mau Mau Uprising.

The Kabaka's Exile and Return

Kabaka Mutesa II of Buganda, also known as "King Freddie," was not very interested in his people's well-being at first. But when the British Governor, Sir Andrew Cohen, wanted Buganda to give up its special status for a bigger nation, the Kabaka refused. Instead, he demanded that Buganda be separate from the rest of the protectorate.

Governor Cohen responded by sending the Kabaka away to London. This made the Kabaka a hero to the Baganda people. It also sparked strong feelings against colonial rule and a desire for Buganda to be separate. Cohen's plan failed, and he couldn't find anyone among the Baganda to support his ideas. After two years of strong opposition from the Baganda, Cohen had to bring Kabaka Freddie back.

The talks to bring the Kabaka back were a big win for the Baganda. The Kabaka agreed not to oppose Uganda's independence as a whole country. In return, he got his position back. Also, for the first time since 1889, the Kabaka could choose and remove his own chiefs (government officials in Buganda). This meant he was no longer just a figurehead but a key player in how Uganda would be governed.

A new group of Baganda called "the King's Friends" strongly supported the Kabaka. They were loyal to Buganda as a kingdom. They would only agree to be part of an independent Uganda if the Kabaka was in charge. Baganda politicians who disagreed with them were called "King's Enemies." This meant they were left out politically and socially.

Political Parties Emerge

One important group that was different was the Roman Catholic Baganda. They formed their own party, the Democratic Party (DP), led by Benedicto Kiwanuka. Many Catholics felt left out because Protestants mostly controlled Buganda's government. The Kabaka had to be Protestant, and his coronation was like that of British kings. Religion and politics were closely linked in other Ugandan kingdoms too. The DP had both Catholic and other members and was very well organized.

Elsewhere in Uganda, the Kabaka's growing political power caused immediate anger. Other political parties and groups had their own disagreements, but they all shared one goal: they did not want Buganda to dominate them. In 1960, a politician from Lango, Milton Obote, formed a new party called the Uganda People's Congress (UPC). This party brought together everyone who opposed Buganda's power, except for the Catholic-led DP.

The steps taken to make Uganda independent led to a split between Buganda and those who opposed its power. In 1959, Buganda had 2 million people out of Uganda's total of 6 million. Even without counting non-Baganda living in Buganda, over 1 million people were loyal to the Kabaka. This was too many to ignore, but too few to control the whole country.

At a meeting in London in 1960, it was clear that Buganda wanting to be separate and Uganda wanting a strong central government could not both happen. No agreement was reached, and the decision on the type of government was put off. The British announced elections for March 1961.

In Buganda, the "King's Friends" told people not to vote because their demands for future independence were rejected. So, when people voted across Uganda, only the Catholic supporters of the DP voted in Buganda. They won 20 of Buganda's 21 seats. This gave the DP the most seats in the national assembly, even though they had fewer votes nationwide than the UPC. Benedicto Kiwanuka became the new chief minister of Uganda.

Shocked by these results, the Baganda who wanted to be separate formed a party called Kabaka Yekka. They changed their minds about boycotting the election. They liked the idea of a federal government, where Buganda would have some internal freedom if it joined the national government. The UPC also wanted to remove the DP from power. So, Obote made a deal with Kabaka Freddie and the Kabaka Yekka party. He accepted Buganda's special federal status and even let the Kabaka choose Buganda's representatives to the national assembly. In return, they would work together to defeat the DP. The Kabaka was also promised the mostly ceremonial role of head of state of Uganda, which was very important to the Baganda.

This alliance between the UPC and Kabaka Yekka led to the defeat of the DP government. After the final election in April 1962, Uganda's parliament had 43 UPC members, 24 Kabaka Yekka members, and 24 DP members. The new UPC-Kabaka Yekka team led Uganda to independence in October 1962. Obote became prime minister, and the Kabaka became the head of state.

Buganda After Independence

Uganda became independent on October 9, 1962. Sir Edward Mutesa II, the Kabaka of Buganda, became Uganda's first president. However, the power of the Buganda monarchy and its special freedom were later taken away, along with those of the other four Ugandan kingdoms.

The biggest issue in Ugandan politics at this time was the role of the kings. Even though there were four kingdoms, the main question was how much control the central government should have over Buganda. The king was a strong symbol for the Baganda. This became very clear after the British government sent him away in 1953. When talks for independence threatened Buganda's freedom, important leaders formed a political party to protect the king. They argued that protecting the king was about the Baganda people surviving as a separate nation. Because of this, supporting the kingship got huge support in local Buganda elections just before independence.

The Monarchy is Removed

In 1967, Prime Minister Apollo Milton Obote changed the constitution. He made Uganda a republic, meaning it no longer had a king as head of state. On May 24, 1966, the Ugandan army attacked the royal palace in Mengo. Uganda's first president and king of Buganda, Kabaka Muteesa II, fled his palace during a heavy rain. He escaped to Burundi and then to Britain, where he later died. The Ugandan army turned the king's palace into their barracks and the Buganda parliament building into their headquarters. It was hard to know how many Baganda still supported the king because no one could openly show their support.

On January 25, 1971, Obote was removed from power in a coup by the head of the army, Idi Amin. After a short time considering it, Idi Amin also refused to bring back the kingdoms. By the 1980s, Obote was back in power. By then, more than half of all Baganda had never lived under their king. A small group called the Conservative Party tried to bring back the king in the 1980 elections but got little support.

The Monarchy Returns

In 1986, the National Resistance Movement (NRM), led by Yoweri Museveni, took power in Uganda. While fighting a war against Obote, NRM leaders were not sure if the Baganda would accept their government. The NRM had mixed feelings about the kingship. On one hand, their fight against Obote happened mostly in Buganda. Many Baganda fighters were part of it, and they relied on the strong dislike most Baganda felt for Obote.

On the other hand, many Baganda who joined the NRM believed that political groups should not be based on ethnic loyalty. However, many Ugandans said that Museveni promised to bring back the kingship and allow Ronald Mutebi, the heir to the throne, to become king. Many other Ugandans strongly opposed this, mainly because of the political advantages it would give Buganda.

A few months after the NRM took over in 1986, the leaders of Buganda's clans started a public campaign. They wanted the kingship to be restored, the Buganda parliament building to be returned, and Mutebi to be allowed back in Uganda. The government tried to control the situation. First, the prime minister, Samson Kisekka, who was a Muganda, told people to stop this "foolish talk."

The government then suddenly canceled celebrations for another kingdom's heir. But newspapers reported more demands for Mutebi's return from Buganda's clan elders. The government then said that the question of restoring kings was for the new Constitutional Assembly to decide, not the current government. Three weeks later, the NRM called supporters of the restoration "disgruntled opportunists" and threatened action against anyone who kept pushing the issue.

At the same time, the president agreed to meet with the clan elders, which gave the issue more public attention. Then, in a surprise move, the president convinced Mutebi to return home secretly in mid-August 1986. Ten days later, the government arrested some Baganda, accusing them of a plot to overthrow the government and restore the king. While Museveni managed to calm down Buganda's strong feelings, he had to go to great lengths to do so, and nothing was truly settled. The kingship issue was expected to come up again when a new constitution was discussed.

The monarchy was finally brought back in 1993. Ronald Muwenda Mutebi II, the son of Mutesa II, became the new Kabaka. Buganda is now a constitutional monarchy. This means the Kabaka is the head of the kingdom, but his powers are limited by a constitution. Buganda has its own parliament called the Lukiiko, which meets in a building called Bulange. The Lukiiko has a speaker, members for the royal family, county chiefs, ministers, clan heads, and guests. The Kabaka only attends two sessions each year: when he opens the first session and when he closes the last session.

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |