History of Nigeria before 1500 facts for kids

The history of Nigeria before 1500 tells us about the very early times in this West African country. It covers the Stone Age, when people first lived there, the Iron Age, when they learned to work with metals, and the rise of powerful kingdoms and states.

Long, long ago, between 780,000 and 126,000 years ago, early humans who used special tools called Acheulean tools might have lived all over West Africa. People from the Middle Stone Age probably lived in West Africa continuously for a long time. Some groups, like the Iwo Eleru people, were still in Nigeria as recently as 13,000 years ago.

Hunter-gatherers in West Africa lived in central Africa over 32,000 years ago. They spread across coastal West Africa by 12,000 years ago and moved north into places like Mali and Burkina Faso between 12,000 and 8,000 years ago.

An amazing discovery in northern Nigeria is the Dufuna canoe. This ancient boat, carved from a tree, is about 6,000 to 6,500 years old. It's the oldest known boat in Africa and the second oldest in the world!

Later, after people moved from the central Sahara desert into Nigeria, the Nok people settled in the Nok region around 1500 BCE. Their culture lasted until about 1 BCE. After this, many kingdoms and states grew strong. These included the Kingdom of Nri (Igbo people), the Kingdom of Benin, the Kingdom of Ife (Yoruba people), the Igala Kingdom, the Hausa Kingdoms, and Nupe. Many smaller states near Lake Chad were taken over or moved as the Kanem–Bornu Empire expanded. Bornu, which was once a part of Kanem, became its own independent kingdom in the late 1300s CE.

Early People in Nigeria

Stone Age Discoveries

Early humans, who used tools from the Acheulean period, might have lived across West Africa between 780,000 and 126,000 years ago. This was during the Middle Pleistocene era.

Middle Stone Age Life

People in the Middle Stone Age likely lived in West Africa without interruption for a long time. They probably weren't there before a period called MIS 5. During MIS 5, these West Africans might have moved across the West Sudanian savanna and stayed in that area. Later, in the Late Pleistocene, they started living along the forest and coastal parts of West Africa. By at least 61,000 years ago, they might have moved south from the savanna. By 25,000 years ago, they may have lived near the coast. The Iwo Eleru people continued to live at Iwo Eleru in Nigeria as late as 13,000 years ago.

Later Stone Age Hunter-Gatherers

Over 32,000 years ago, or by 30,000 years ago, Late Stone Age hunter-gatherers lived in the forests of western Central Africa. A very dry period, called the Ogolian period, happened between 20,000 and 12,000 years ago. By 15,000 years ago, as the weather became more humid and the West African forest grew, there were fewer Middle Stone Age settlements and more Late Stone Age hunter-gatherer settlements.

Later Stone Age Africans, who used smaller tools, replaced earlier groups who used larger tools. These new groups moved from Central Africa into West Africa. Between 16,000 and 12,000 years ago, Late Stone Age West Africans began living in the eastern and central forest regions, including Ghana, Ivory Coast, and Nigeria. Some West African hunter-gatherers continued to live in the forest-savanna areas until about 1000 years ago, or even later. Eventually, they mixed with and adopted the ways of larger groups of farmers, similar to how the Bantu-speaking farmers interacted with Central African hunter-gatherers. In northeastern Nigeria, a unique language called Jalaa might be a language that came from the original languages spoken by these early West African hunter-gatherers.

Iron Age Beginnings

Learning how to work with iron, called iron metallurgy, started in many places across Africa, including West, Central, and East Africa. This shows that these iron-working skills were developed by Africans themselves.

Archaeologists have found ancient iron smelting furnaces and waste material (slag) in the Nsukka region of southeastern Nigeria, in what is now Igboland. These sites date back to 2000 BCE at Lejja and 750 BCE at Opi. It's also thought that iron working might have been developed independently by the Nok culture between the 9th and 6th centuries BCE. More recent studies suggest that iron metallurgy happened even earlier in Nigeria, around 2631-2458 BCE at Lejja.

Nok Culture Flourishes

The Nok people and the Gajiganna people might have moved from the central Sahara desert. They brought pearl millet (a type of grain) and pottery with them. They settled in different parts of northern Nigeria, in the regions of Gajiganna and Nok. The Nok culture likely began around 1500 BCE and lasted until about 1 BCE.

The Nok people created amazing terracotta sculptures (sculptures made from baked clay). They made these on a large scale, possibly as part of a complex system of burial rituals that included feasting. The earliest Nok terracotta sculptures might have been made around 900 BCE. Some of these sculptures show figures holding slingshots, bows, and arrows, suggesting that the Nok people hunted or trapped wild animals.

One Nok sculpture even shows two people in a dugout canoe, paddling with their goods. This suggests that the Nok people used dugout canoes to transport goods along rivers, like the Gurara River, which flows into the Niger River. They likely traded these goods in a regional network. Another Nok sculpture shows a figure with a seashell on its head, which might mean their river trade routes reached all the way to the Atlantic Ocean coast.

The Dufuna canoe, found in northern Nigeria, is much older, built about 8,000 years ago. The Nok terracotta depiction of a dugout canoe, made in central Nigeria around 1000 BCE, is the second oldest image of a boat in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Later art traditions in West Africa, such as those from Bura (Niger), Koma (Ghana), Igbo-Ukwu (Nigeria), Jenne-Jeno (Mali), and Ile Ife (Nigeria), might have been influenced by the earlier Nok terracotta tradition. Most Nok settlements are found on mountaintops. At one site, Kochio, a settlement wall was carved from granite. A large stone fence was also built around the enclosed settlement of Kochio. Another site, Puntun Dutse, had a circular stone foundation of a hut.

As mentioned, iron metallurgy may have been developed independently by the Nok culture between the 9th and 6th centuries BCE. Because of similar cultural and artistic styles, the Yoruba, Jukun, or Dakakari peoples, who speak Niger-Congo languages, might be descendants of the Nok peoples. The bronze figures of the Yoruba Ife Empire and the Bini Kingdom of Benin also show stylistic similarities to Nok terracottas, suggesting they continued these ancient traditions.

Rise of Kingdoms and States

Kingdom of Nri (Igbo)

The Kingdom of Nri in the Awka area was founded around 900 AD in north-central Igboland. It is thought to be the oldest kingdom in Nigeria. The Nsukka-Awka-Orlu area is considered the oldest place where Igbo people settled and is their homeland. Nri was a center for spiritual beliefs, learning, and trade. The Nri people were known for promoting peace and harmony, and their influence spread beyond Igboland. Their influence reached southern Igalaland and the Benin Kingdom between the 12th and 15th centuries.

The Nri people were great travelers and business people, involved in long-distance trade across the Sahara desert. The advanced nature of their civilization is clear from the bronze castings found in Igbo Ukwu, an area influenced by Nri. The Benin Kingdom became a challenge to Nri in the 15th century under Oba Ewuare. The Nri kingdom's power declined when the trade in people was at its peak in the 18th century, as they were against it. The Benin and Igala empires, which were involved in this trade, then became the main powers influencing the western and northern Igbo areas, which were once Nri's main areas of operation. After Nri's decline in the 18th century, other Igbo groups, like the Aro Confederacy and Ohafia peoples, became important influences in Igboland through their trading activities.

Edo Kingdom (Benin)

During the 15th century, the Benin Kingdom was one of the first in the region to meet foreign traders.

The Edo people first formed a community east of Ubini, in a Yoruba-speaking area. It became part of the Benin Kingdom in the early 14th century. By the 15th century, Benin became a strong trading power on its own. It blocked the Ife kingdom's access to coastal ports, just as Oyo had cut off Ife from the savanna. Political and religious power in Benin rested with the oba (king), who was traditionally believed to be a descendant of Oduduwa, the first ruler of Ife. Benin grew to cover a large area, protected by many circular earth walls. By the late 15th century, the Edo Kingdom was in contact with Portugal, trading resources like palm oil and cotton. At its strongest in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Edo Kingdom included parts of southeastern Yorubaland and western parts of what is now Delta State.

Yoruba and Benin Kingdoms

Historically, the Yoruba people were the main group living on the west side of the Niger River. They were formed from different groups of migrants over time. The Yoruba were organized into family groups living in village communities, and they made their living through farming. From about the 8th century, nearby village compounds, called Ilé, joined together to form many city-states. In these states, loyalty to the clan became less important than loyalty to the ruling family. The earliest known city-states were formed at Ilé-Ifẹ̀ and Ijebuland.

As cities grew, there was also a high level of artistic achievement. This was especially true for terracotta and ivory sculptures, and the skilled metal casting produced at Ilé-Ifẹ̀. The Yoruba worshipped many gods, led by a main deity called Olorun. There were also lesser gods who performed different tasks. Oduduwa was seen as the creator of the earth and the ancestor of the Yoruba kings. According to their myths, Oduduwa founded Ife and sent his sons to establish other cities, where they ruled as priest-kings. Ile Ife was a center for as many as 400 religious groups, and their traditions were used by the Ooni of Ilé-Ifẹ̀ (king) to gain political power.

The Ooni was chosen from a branch of the ruling family on a rotating basis. Once chosen, they were kept separate from others. Below the Ooni, the state had palace officials, town chiefs, and rulers of areas outside the main city. The way Ife was governed was later adopted by Oyo. Eventually, Oyo became a constitutional monarchy, though this wasn't its original form of government. Unlike other Yoruba groups, Oyo had cavalry (soldiers on horseback). This helped them develop trade further north.

Northern Kingdoms of the Sahel

Trade was very important for the growth of organized communities in the savanna parts of Nigeria. Early people, adapting to the spreading desert, were spread out by the third millennium BCE, when the Sahara began to dry up. Trade routes across the Sahara desert connected the western Sudan region with the Mediterranean Sea since the time of Carthage, and with the Upper Nile even earlier. These routes allowed for communication and cultural exchange until the late 1800s. Through these same routes, the religion of Islam spread south into West Africa after the 9th century AD.

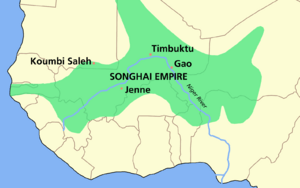

By then, a series of states ruled by families, including the earliest Hausa Kingdoms, stretched across the western and central Sudan. The most powerful of these states were Ghana, Gao, and Kanem. While these were not within modern Nigeria's borders, they still influenced the history of the Nigerian savanna. Ghana declined in the 11th century but was followed by the Mali Empire, which brought much of the western Sudan under its control in the 13th century. After Mali broke up, a local leader named Sonni Ali founded the Songhai Empire in the middle Niger region and western Sudan. He took control of the trans-Saharan trade. Sunni Ali captured Timbuktu in 1468 and Jenne in 1473, building his rule on trade income and the help of Muslim merchants. His successor, Askiya Mohammad Ture, made Islam the official religion, built mosques, and brought Muslim scholars to Gao.

Even though these western empires had little direct political influence on the Nigerian savanna before 1500, they had a strong cultural and economic impact. This became even more noticeable in the 16th century, especially because these states were linked to the spread of Islam and trade. Throughout the 16th century, much of northern Nigeria paid respect to either Songhai in the west or Bornu, a rival empire, in the east.

Kanem-Bornu Empire

Bornu's history is closely tied to Kanem, which had become a powerful empire in the Lake Chad basin by the 13th century. Kanem expanded westward to include the area that later became Bornu. The mai (king) of Kanem and his court accepted Islam in the 11th century, just like the western empires. Islam was used to strengthen the state's political and social structures, though many older customs were kept. For example, women continued to have significant political influence.

The mai used his mounted guards and an early army of nobles to spread Kanem's power into Bornu. Traditionally, this territory was given to the heir to the throne to govern while they were learning. However, in the 14th century, conflicts within the ruling family forced the leaders and their followers to move to Bornu. As a result, the Kanuri people emerged as an ethnic group in the late 14th and 15th centuries. The civil war that affected Kanem in the second half of the 14th century led to Bornu becoming independent.

Bornu's wealth came from the trans-Sudanic trade in people and the desert trade in salt and livestock. To protect its business interests, Bornu had to get involved in Kanem, which remained a place of conflict throughout the 15th and into the 16th centuries. Despite being somewhat politically weak during this time, Bornu's court and mosques, supported by a line of scholarly kings, became famous centers of Islamic culture and learning.

Hausa States

By the 11th century, some Hausa states, such as Kano, Katsina, and Gobir, had grown into walled towns. They were involved in trade, serving camel caravans, and making various goods. Until the 15th century, these small states were on the edge of the larger Sudanic empires of that time. They were constantly pressured by Songhai to the west and Kanem-Bornu to the east, to whom they paid tribute (payments to a more powerful state). Armed conflicts were usually about economic reasons. Hausa states would form alliances to fight against the Jukun and Nupe peoples in the middle belt to capture people for trade, or they would fight each other for control of trade routes.

Islam reached Hausaland along the caravan routes. The famous Kano Chronicle tells how Kano's ruling family converted to Islam through clerics from Mali, showing that Mali's imperial influence reached far to the east. Accepting Islam was a slow process, and it was often just for show in the countryside, where traditional folk religions remained strong. Nevertheless, Kano and Katsina, with their famous mosques and schools, became full participants in the cultural and intellectual life of the Islamic world.

The Fulani people began to enter the Hausa country in the 13th century. By the 15th century, they were raising cattle, sheep, and goats in Bornu as well. The Fulani came from the Senegal River valley, where their ancestors had developed a way of managing livestock by moving them between different pastures (called transhumance). Gradually, they moved eastward, first into the centers of the Mali and Songhai empires, and eventually into Hausaland and Bornu. Some Fulani converted to Islam as early as the 11th century and settled among the Hausa. They became so integrated that they were ethnically hard to tell apart. They formed a very religious and educated group who became essential to the Hausa kings as state advisors, Islamic judges, and teachers.

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |