Huilliche uprising of 1712 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Huilliche uprising of 1712 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Huilliches of Chiloé | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 30 Spaniards | 400 Huilliches | ||||||

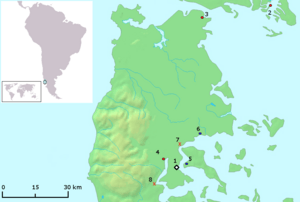

The Huilliche uprising of 1712 (also known as Rebelión huilliche de 1712 in Spanish) was a major event. It was a rebellion by the Huilliche people against the Spanish encomenderos (Spanish lords who controlled indigenous labor). This happened in the Chiloé Archipelago, which was part of the Captaincy General of Chile at the time. The uprising took place in the central area of the islands.

Why the Uprising Happened

The Huilliche people of Chiloé had a history of resisting Spanish rule. Back in 1600, some Huilliches even helped a Dutch pirate named Baltazar de Cordes attack the Spanish town of Castro.

Unlike other parts of Chile, the number of indigenous people in Chiloé actually grew after 1700. By 1712, about half of the archipelago's population was indigenous.

The encomienda system in Chiloé was very harsh. In this system, Spanish encomenderos were given control over groups of indigenous people. These people were supposed to work for the Spanish. In return, the encomenderos were meant to protect them and teach them about Christianity.

However, many encomenderos in Chiloé did not follow the rules. They often didn't pay the Huilliches for their work. They also ignored laws that said indigenous workers should have free time. One common job was traveling to the mainland to cut down alerce trees for wood.

The Huilliches felt that a man named José de Andrade was particularly unfair. They saw his actions as a main reason for the rebellion. For example, he was known for giving very harsh punishments. He would also judge people himself and not pay them. His son and his majordomo (a person in charge of a household) were also accused of similar bad behavior. The majordomo was even said to have kidnapped children and sent them to mainland Chile.

Because of these many injustices, the Huilliches decided to act. On January 26, 1712, they met and planned their uprising. They set the date for February 10. Their main goal was not to completely end Spanish rule. Instead, they wanted revenge for the unfair treatment they had suffered.

The Uprising Begins

The Huilliches planned to attack Castro. This town was the main political and economic center of the islands. Most Spaniards lived there, and it was where most encomiendas were located.

On the night of February 10, the rebellion began. Huilliches attacked the homes and haciendas (large estates) of Spaniards in central Chiloé. Spaniards were killed, and buildings were set on fire. Some Spaniards managed to hide and defend themselves in Castro. They were surrounded by the rebels. Spanish women and children were taken as prisoners during the attacks.

During the first night, only important Spaniards were killed. Spaniards of lower social standing, indigenous people who had adopted Spanish culture, friars, or priests were not attacked. Other Spaniards survived by hiding in the forests.

After the rebellion was put down, a small group of Huilliches left Chiloé. They went to the Guaitecas Archipelago to avoid harsh punishment from the Spanish. Other rebels sought safety with Father Manuel del Hoyo. He was at the Mission of Nahuel Huapi, located across the Andes mountains.

What Happened Next

After the rebellion, José Marín de Velasco, who was the Royal Governor of Chiloé, was removed from his position. However, he later received approval from the King of Spain. He returned to govern Chiloé in 1715. His goal was to make sure the encomienda system followed the law.

After the uprising, the Huilliches made more complaints to the Spanish authorities. This rebellion helped bring attention to their unfair treatment.

The encomienda system was eventually ended. It was abolished in Chiloé in 1782. In the rest of Chile, it ended in 1789. Finally, the system was completely abolished across the entire Spanish Empire in 1791.

See also

In Spanish: Rebelión huilliche de 1712 para niños

In Spanish: Rebelión huilliche de 1712 para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |