InSight facts for kids

The InSight lander with its solar panels opened up in a special clean room before its flight.

|

|

| Names |

|

|---|---|

| Mission type | Mars lander |

| Operator | NASA / JPL |

| Mission duration | |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Martin Space |

| Launch mass | 694 kg (1,530 lb) |

| Landing mass | 358 kg (789 lb) |

| Dimensions | 6.0 × 1.56 × 1.0 m (19.7 × 5.1 × 3.3 ft) (with solar panels open) |

| Power | 600 watts |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 5 May 2018, 11:05:01 UTC |

| Rocket |

|

| Launch site | Vandenberg, SLC-3E |

| Contractor | United Launch Alliance |

| Entered service | 26 November 2018 |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | Decommissioned |

| Declared | 21 December 2022 |

| Last contact | 15 December 2022 |

| Mars lander | |

| Landing date | 26 November 2018, 19:52:59 UTC |

| Landing site | Elysium Planitia 4°30′09″N 135°37′24″E / 4.5024°N 135.6234°E |

| Flyby of Mars | |

| Spacecraft component | Mars Cube One (MarCO) |

| Closest approach | 26 November 2018, 19:52:59 UTC |

| Distance | 3,500 km (2,200 mi) |

InSight mission logo |

|

InSight (which stands for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport) was a robotic lander sent to study the inside of the planet Mars. It was like a doctor giving Mars a check-up, listening to its "heartbeat" and taking its temperature. The mission was built by Lockheed Martin Space and managed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

The mission launched on May 5, 2018, and landed safely on a flat plain on Mars called Elysium Planitia on November 26, 2018. For over four years, InSight studied the planet and discovered that Mars is still geologically active, meaning it has "marsquakes" (like earthquakes on Earth).

InSight's main goals were to place a super-sensitive listening device called a seismometer on the surface to detect marsquakes and to use a heat probe to measure how much heat is flowing out from inside the planet. By studying these things, scientists hoped to learn how rocky planets like Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars first formed billions of years ago.

The mission officially ended in December 2022. So much dust had collected on InSight's solar panels that it could no longer get enough power from the Sun to operate.

Contents

What Was InSight's Mission?

The main goal of the InSight mission was to study the early history of Mars. By learning about the planet's core, mantle (the layer under the crust), and crust, scientists can understand how all the rocky planets in our solar system were formed.

Think of it like baking a cake. All the rocky planets started with the same basic ingredients. But over time, they all turned out differently. InSight's job was to figure out why Mars turned out the way it did. The mission tried to answer big questions:

- Is Mars still "alive" inside? Does it have seismic activity (marsquakes)?

- How much heat is still coming from the planet's core?

- How big is the core of Mars, and is it liquid or solid?

Mars is a perfect place to study this because it's not as big as Earth but not as small as the Moon. This means it holds a good record of how planets were built long ago.

In March 2021, scientists announced that based on the marsquakes InSight detected, they figured out that the core of Mars is liquid and about half the size of Earth's core.

A Huge Discovery: Water Deep Underground

Even after the mission ended, data from InSight led to an amazing discovery. In August 2024, scientists studying the vibrations from marsquakes found evidence of a huge amount of liquid water deep underground.

The water is not like a big open ocean. Instead, it's trapped in tiny cracks in the rock, about 10 to 20 kilometers (6 to 12 miles) below the surface. Scientists estimate there could be enough water to cover the entire planet in an ocean over 1.6 kilometers (1 mile) deep if it were all brought to the surface. This was a major finding that changed our understanding of Mars.

Listening to Mars's Heartbeat

Just like doctors use a stethoscope to listen to a person's heart, scientists use seismometers to listen to the vibrations inside a planet. These vibrations can be caused by quakes or even by meteorites hitting the surface.

Long ago, the Viking landers in the 1970s also carried seismometers to Mars, but they didn't work very well. One didn't deploy correctly, and the other was attached to the lander, so it picked up vibrations from the wind, making it hard to detect real marsquakes.

InSight's seismometer was placed directly on the Martian ground and was covered by a shield to protect it from wind and temperature changes. This allowed it to be extremely sensitive. Astronauts also left seismometers on the Moon during the Apollo program, which discovered "moonquakes." InSight's data allowed scientists to compare the insides of Earth, the Moon, and Mars for the first time.

On May 4, 2022, InSight detected the biggest marsquake ever recorded, estimated at a magnitude 5.

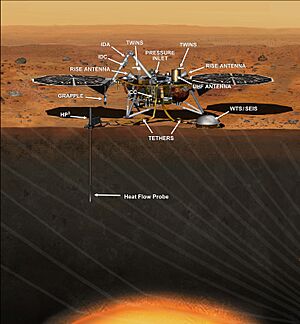

InSight's Science Tools

InSight carried a set of amazing tools to study Mars. The total weight of the science equipment was about 50 kg (110 pounds).

- SEIS (Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure): This was the mission's most important instrument. It was a dome-shaped seismometer so sensitive it could detect vibrations smaller than the width of an atom. It was built by the French space agency (CNES) and other European partners. It listened for marsquakes and meteorite impacts.

- HP³ (Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package): This instrument was nicknamed "the mole." It was designed to be a self-hammering nail that would dig 5 meters (16 feet) into the Martian soil to measure the planet's temperature. It was built by the German Aerospace Center (DLR).

- RISE (Rotation and Interior Structure Experiment): This experiment used the lander's radio signals to track Mars's location with extreme precision. By watching how Mars wobbles as it spins, scientists could learn more about the size and density of its core.

- TWINS (Temperature and Winds for InSight): A set of weather sensors, built in Spain, that measured temperature, wind, and pressure at the landing site.

- Cameras: InSight had two cameras. One on its robotic arm to help place the instruments, and another on the front of the lander to give a wide view of the workspace.

The Trouble with the 'Mole'

One of the biggest challenges of the mission was getting the HP³ mole to work. When it started digging in February 2019, it quickly got stuck. The Martian soil at the landing site was different than expected. It was clumpy and didn't provide enough friction for the mole to dig.

For nearly two years, the mission team on Earth tried everything to get it moving. They even used InSight's robotic arm to push down on the mole, a move that was never planned. They called this "pinning." While they managed to get the mole completely buried, it never reached the depth needed to take its measurements. In January 2021, the team announced they were giving up on the mole. Even though it didn't work as planned, the effort taught engineers a lot about working on Mars.

The Long Trip to the Red Planet

Launch

InSight launched on May 5, 2018, from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. It was the first time a mission to another planet had launched from the West Coast of the United States. The powerful Atlas V rocket carried the spacecraft into the sky.

The journey to Mars took about 6.5 months and covered 484 million kilometers (301 million miles).

Landing on Mars

Landing on Mars is one of the hardest things to do in space exploration. The whole process, from hitting the atmosphere to touching down, takes about seven minutes.

Here's how InSight landed on November 26, 2018:

- The spacecraft separated from its cruise stage, which carried it through space.

- It entered the Martian atmosphere at over 19,800 km/h (12,300 mph), protected by a heat shield that glowed red-hot.

- A huge parachute opened to slow it down dramatically.

- The heat shield was jettisoned, and the lander's legs popped out.

- About a kilometer above the ground, the lander separated from the parachute and fired its own rockets to control its final descent.

- It touched down gently on the surface at a speed of about 8 km/h (5 mph), the speed of a slow jog.

Mission control at JPL received a signal that the landing was successful, and the whole team erupted in cheers.

A Scientist on the Martian Surface

A few hours after landing, InSight opened its two large, circular solar panels to start soaking up energy from the Sun. On its very first day, it set a record for the most power ever generated by a spacecraft on Mars in a single day.

Over the next few months, the team used the lander's robotic arm to carefully place the SEIS seismometer and its protective shield on the ground. This was the first time a robot had ever placed an instrument on the surface of another planet.

In April 2019, InSight detected its very first marsquake. It was a tiny rumble, but it was proof that Mars was seismically active. The lander also recorded the sound of the Martian wind, which scientists described as a "low, haunting rumble."

Dust Ends the Mission

InSight was powered by sunlight, but Mars is a dusty place. Over the years, a thick layer of red dust built up on its solar panels, slowly reducing the amount of power it could generate. The team tried a clever trick: using the robotic arm to scoop up sand and trickle it over the panels, letting the wind blow the sand grains to knock some dust off. It worked for a while, but it wasn't enough.

By May 2022, the panels were so covered in dust that NASA announced the mission would likely end soon. InSight sent its last communication to Earth on December 15, 2022, and the mission was officially declared over a few days later.

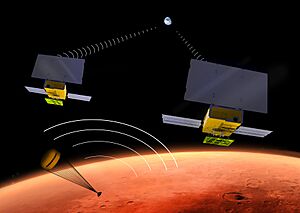

MarCO: The Mini-Messengers

InSight didn't travel to Mars alone. It was accompanied by two small, briefcase-sized spacecraft called Mars Cube One, or MarCO-A and MarCO-B. They were a technology experiment to see if tiny satellites, known as CubeSats, could survive the journey through deep space.

Their main job was to fly past Mars during InSight's landing and relay its signals back to Earth in real-time. They worked perfectly, proving that small, low-cost satellites could be used for future missions to other planets. After their job was done, they flew past Mars and into deep space.

A Mission for Everyone

The InSight mission was a team effort involving scientists and engineers from many countries, including the United States, France, Germany, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Poland.

NASA also invited the public to be part of the mission. People could submit their names to be placed on a tiny microchip carried on the lander. Two chips were installed, carrying a total of 2.4 million names to the surface of Mars.

Gallery

See also

In Spanish: InSight para niños

In Spanish: InSight para niños

- Exploration of Mars

- List of missions to Mars

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |