India Juliana facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Juliana

|

|

|---|---|

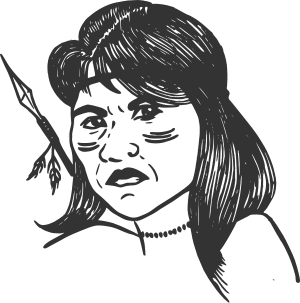

Modern depiction of the India Juliana, used in the logo of a Paraguayan indigenous women's organization.

|

|

| Born | 16th century Paraguay River basin

|

| Died | c. 1542 Asunción, present-day Paraguay, colonial Spanish America

|

| Nationality | Guaraní |

| Known for | Killing her Spaniard master or husband and urging other indigenous women to do the same. |

Juliana, often called the India Juliana (which means "Juliana the Indian" in Spanish), was a brave Guaraní woman. She lived in Asunción, a city founded by the Spanish in early Paraguay. Juliana is known for taking a stand against a Spanish colonist between 1539 and 1542.

Many indigenous women like Juliana were taken by the Spanish. They were forced to work and have children for the colonists. Since the area didn't have much gold, the Spanish made money by forcing indigenous people to work.

We know about India Juliana from writings by Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. He was a Spanish leader who ruled the area for a short time. His scribe, Pero Hernández, also wrote about her. They said Juliana used herbs to poison a Spanish settler named Ñuño de Cabrera. He was either her husband or her master. Even though she admitted it, she was first set free.

When Cabeza de Vaca arrived in Asunción, he heard about Juliana's actions. He learned she even boasted about what she did to other women. To punish her and warn others, he ordered her execution.

India Juliana is seen as a very important person in the women's history of Paraguay. Her act of encouraging other women to resist is considered one of the first recorded indigenous uprisings. There are many stories about her, each with different ideas. While the main part of her story stays the same, details like the date or how she was executed can change.

Some people see India Juliana as someone who helped build the Paraguayan nation. Others see her as a rebel and a symbol of indigenous resistance against Spanish rule. Many modern thinkers see her as an early feminist. Activists and scholars often look to her as an inspiring figure. A street in Asunción was named after her in 1992. This is special because few streets are named after individual indigenous people.

Contents

Life in Early Colonial Paraguay

The first Spanish explorers came to Paraguay hoping to find gold. In 1537, the Spanish built a fort called Nuestra Señora de la Asunción. It was on the Paraguay River.

The Spanish met the local Guaraní people. They made agreements with the Guaraní leaders, called caciques. As part of these agreements, women were given to the Spanish. At first, this was part of a Guaraní custom called cuñadazgo. This custom helped create peace and friendship. It made the Spanish leader like a brother-in-law or son-in-law.

But the Spanish did not treat the Guaraní as equals. They wanted to control them. This led to many indigenous uprisings. There were violent events in 1538–1539, 1542–1543, and 1545–1546. In 1541, a Spanish colonist named Domingo Martínez de Irala wrote that 300 indigenous women lived in Asunción. They had been given to the Spanish by the Cario people to serve them.

In 1541, the Spanish left their first settlement in Buenos Aires because of attacks. They moved to Asunción. This made Asunción a very important center for Spanish rule in the southern part of South America.

Forced Labor and Resistance

The Spanish soon realized there was no gold in the region. So, they started making money by forcing indigenous people to work. They also made them slaves. This led to mass deportations called rancheadas. Women were taken from their homes and forced to work for the colonists.

These violent rancheadas began around 1543. They became very common two years later. Native women were enslaved as servants and mothers. They quickly became like goods to be bought and sold. Asunción became a center for sending indigenous slaves to other places.

Domingo Martínez de Irala was in charge of the Spanish area called the Governorate of New Andalusia. He had been elected by his peers in 1538. This happened after the appointed governor, Juan de Ayolas, went missing.

When the Spanish Court heard Ayolas was likely dead, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca was named the new leader. He arrived in Asunción on March 11, 1542. He took power from Irala. Cabeza de Vaca tried to bring order and protect the indigenous people.

However, Cabeza de Vaca's rule did not last long. After a failed trip to find a route to Peru in 1542, Spanish settlers became unhappy. Irala led a plan against him in 1544. Irala was re-elected as governor. Cabeza de Vaca was arrested and sent to Spain. People said he was too "easy on the natives."

With Irala back in power, the rancheadas became even more common. One researcher said these rancheadas were a very strong way to change indigenous cultures. Whole villages lost their women, causing great pain to the indigenous people.

Juliana's Story in History

The historical mentions of India Juliana are short. But they show a different picture from how Guaraní women were usually described. The main source is a report Cabeza de Vaca gave in 1545. It was called Comentarios. His scribe, Pero Hernández, actually wrote it for him.

Cabeza de Vaca later published a book in 1555. But he left out the part about India Juliana. He also left out other parts that showed his use of violence. He wanted to avoid anything that could be misunderstood.

An earlier mention of Juliana's case, without her name, was written by Hernández in 1545. He wrote about the problems in the area since Governor Ayolas disappeared.

Cabeza de Vaca's story about India Juliana aimed to show the "chaos" that Irala's rules had caused. By writing that India Juliana told other women she was the only brave one to kill her master, Cabeza de Vaca showed her pride. He also showed that she encouraged others to do the same. One researcher felt her revenge "crossed ethnic and gender barriers at the same time."

What Historians Say

Over time, many different stories about India Juliana have appeared. Some are from history books, others from literature. Depending on their views, some describe her as a warrior and a symbol of indigenous resistance. Others see her as someone who helped build the Paraguayan nation.

Even though details like the year (between 1539 and 1542) or how she killed Cabrera differ, the main story is usually the same. She took action against her master and urged other women to do the same. For this, she was arrested and later executed. This was a warning to others not to follow her example.

Some nationalist stories, from both the right and left, focus on her "fighting spirit." They show India Juliana as a hero who fought the Spanish enemy. They say she defended the dignity of the Paraguayan nation, not just the Guaraní people.

Because she encouraged other indigenous women to act against their masters, India Juliana is often seen as a Guaraní warrior. She is thought to have led an uprising of indigenous women against Spanish rule. Her rebellion is considered one of the earliest recorded indigenous uprisings. Some stories say India Juliana was the daughter of a cacique. This was common for women given away in early agreements.

Historians like Oscar Creydt and Idalia Flores de Zarza have written about her. Flores de Zarza even said Juliana died by hanging. Most modern historians use these sources. This includes Argentines Felipe Pigna and Loreley El Jaber. Historian Roberto A. Romero wrote that in 1542, "Guaraní women were the main figures of the big plan against the Spanish colonizers, led by the India Juliana." He added that she "killed her Spanish husband Ñuño Cabrera and went out to walk the streets of the city, telling the natives to do the same with their European husbands to get rid of all the conquerors." He wrote that the plan was stopped and Juliana "died by hanging."

Juliana's Legacy Today

Today, India Juliana is seen as a historical defender of indigenous peoples. She is also a symbol of women's freedom. Many modern writers see her as an early feminist. Several feminist groups, schools, and centers for indigenous women in Paraguay are named after her.

Andrés Colmán Gutiérrez, a writer, said she is "carried as a banner" in yearly marches for International Women's Day. He called her "perhaps the first feminist indigenous Guaraní heroine." He said she was a rebel against the macho and patriarchal culture. She challenged the easy official story of the Spanish conquest in Paraguay.

Paraguayan scholars and activists see India Juliana as an important ancestor. This is part of a movement to find "feminist and women's family trees" in South America. They want to move away from a European-focused view. Similar figures are celebrated in other countries. For example, Dolores Cacuango and Tránsito Amaguaña in Ecuador. Also, Bartolina Sisa and Micaela Bastidas in the Andes. And María Remedios del Valle and Juana Azurduy in Argentina.

In 1992, the government of Asunción named a street "India Juliana." It is one of the few streets named after an individual indigenous person. Other streets are named after caciques like Arecayá and Lambaré. While naming a street after her was good, the reason given was controversial. It said she helped the colonists as a guide. This made her seem like a "cultural mother" who helped unite both cultures.

India Juliana is considered one of the most important figures in the women's history of Paraguay. Her image has been used on products like T-shirts and beers. In 2020, her story was made into a comic book. It was part of the "Mundo guaraní" collection. The comic shows her as a Guaraní heroine fighting Spanish rule. It gives her the native name Arapy, which means "world" or "universe" in the Guaraní language. Paraguayan singer-songwriter Claudia Miranda also included a song about India Juliana on her 2020 album Las brujas.

See also

- Apacuana

- Indigenous peoples in Paraguay

- List of Paraguayans

- List of people who were executed

- List of rebellions

- List of slaves

- List of uprisings led by women

- List of women who led a revolt or rebellion

- Slave rebellion

- Women in Paraguay

In Spanish: India Juliana para niños

In Spanish: India Juliana para niños