Indigenous peoples of Costa Rica facts for kids

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 114,000 2.4% of Costa Rica's population |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Indigenous languages, Spanish | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Indigenous peoples of the Americas |

The Indigenous people of Costa Rica, also called Native Costa Ricans, are the first people who lived in the land now known as Costa Rica. They were here long before Europeans and Africans arrived. Today, about 114,000 indigenous people live in Costa Rica. This makes up about 2.4% of the country's total population. These communities work hard to keep their unique cultures, traditions, and languages alive.

In 1977, the Costa Rican government passed a law called the Indigenous Law. This law helped create special areas called reserves for indigenous groups. There are now 24 indigenous territories across Costa Rica. Even though they only gained the right to vote in 1994, indigenous people are still working to protect their rights. They especially want to make sure their land is safe and that laws meant to protect them are followed. Costa Rica also signed the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007.

There are eight main indigenous groups in Costa Rica.

Contents

- History of Indigenous Peoples in Costa Rica

- Indigenous Groups in Costa Rica

- Boruca People: Southern Costa Rica

- Bribri People: Southern Atlantic Coast

- Cabécar People: Cordillera de Talamanca

- Guaymí People: Southern Costa Rica, near Panama

- Huetar People: Quitirrisí

- Maleku People: Northern Alajuela

- Matambú or Chorotega People: Guanacaste

- Térraba or Teribe People: Southern Costa Rica

- Current Challenges for Indigenous Communities

- See also

History of Indigenous Peoples in Costa Rica

The first indigenous people in what is now Costa Rica were hunters and gatherers. They lived by hunting animals and gathering plants for food. This land was special because it was between two big cultural areas: Mesoamerica (like ancient Mexico) and the Andean region (like ancient Peru). Indigenous peoples have lived in Costa Rica for at least 10,000 years.

When the Spanish arrived in the 1500s, the northwest part of Costa Rica, the Nicoya Peninsula, was influenced by Mesoamerican cultures. The Nicoya culture was the largest "cacicazgo" (a type of chiefdom) on the Pacific coast. The central and southern parts of the country were part of the Isthmo-Colombian Area. People here spoke Chibchan languages. The Diquis culture was very strong from 700 CE to 1530 CE.

Christopher Columbus reached Costa Rica in 1502 on his last trip to the Americas. Later, another Spanish explorer, Gil Gonzalez Dávila, named the land "Costa Rica" (Rich Coast). He thought he had found a lot of gold there. The Spanish found that the indigenous groups in Costa Rica lived in smaller, separate communities. This was different from the larger empires they had seen elsewhere.

During the time of Spanish colonization, Costa Rica was quite poor. It was far from most of the main Spanish colonies. Early Spanish settlements often failed because of diseases and the challenging tropical rainforest weather. Costa Rica only became a Spanish province in the 1560s. By then, a community had started using the rich volcanic soil for farming. When Columbus arrived, there were about 20,000 native Costa Ricans. But this number dropped a lot because of diseases like smallpox. Many indigenous people were also forced into slavery, and some escaped.

Indigenous Groups in Costa Rica

Boruca People: Southern Costa Rica

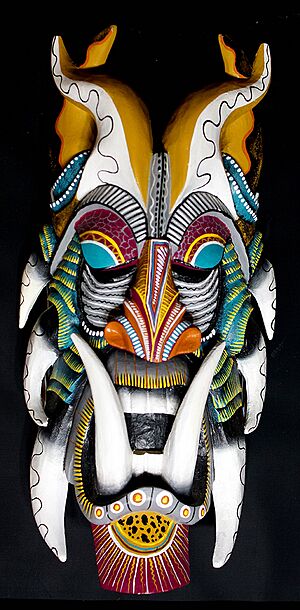

About 2,660 people belong to the Boruca tribe. They live in the Puntarenas area of Costa Rica. Their land was one of the first reserves set up for indigenous Costa Ricans. The Boruca are well-known for their crafts, especially the masks they make. These masks are used in the "Fiesta de los Diablos" (Festival of the Devils). This three-day festival shows a play where the Boruca people (as devils) fight against the Spanish conquistadors (as bulls).

Bribri People: Southern Atlantic Coast

The Bribri are an indigenous tribe living in areas like Salitre, Cabagra, Talamanca Bribri, and Kekoldi. Their population ranges from 11,000 to 35,000 people. The Bribri have a special social structure based on clans. Each clan is made up of a large extended family. Women have an important role in Bribri society. Children belong to their mother's clan, and only women can inherit land. Women are also the only ones who can prepare the sacred cacao drink used in rituals. Men's roles are set by their clan, and some are only for men. The spiritual leader, called an "awa", is very important to the Bribri. Men can become an awa.

Like many other indigenous groups, Cacao (chocolate) is very special to the Bribri. They believe the cacao tree used to be a woman who the god Sibú turned into a tree. Only women are allowed to prepare the cacao drink. Many groups now make handmade chocolate, which helps these women.

Cabécar People: Cordillera de Talamanca

The Cabécar are the largest indigenous group in Costa Rica. They are also considered the most isolated. They live high up in the Chirripo Mountains, which can take hours to reach by hiking. Because of this, many Cabécar people have not been exposed to modern items or much formal education. They are very traditional and have kept their culture strong. Most of them speak their own language rather than Spanish.

Guaymí People: Southern Costa Rica, near Panama

The Guaymís, also known as the Ngabe, are a large group in Costa Rica. They moved from Panama to Costa Rica in the 1960s. Their main way of earning money is through farming. They grow crops like bananas, rice, corn, and beans.

Huetar People: Quitirrisí

The Huetar people live in Ciudad Colon and Puriscal in the Central Valley. They are known for making beautiful handwoven baskets and straw hats.

Maleku People: Northern Alajuela

The Maleku are an indigenous group of about 600 people. They live in the San Rafael de Guatuso Indigenous Reserve. Before the Spanish arrived, their land was much larger. It included places like Rincon de la Vieja and Arenal volcano, which were sacred sites. Today, their reserve is about an hour north of La Fortuna. They are working to buy back some of their original land from the government. The Maleku earn money by selling indigenous art. Tourists can also watch them perform music in nearby La Fortuna. Their traditional houses are in danger because the special trees used to build them are also endangered. The Maleku are working hard to protect their language, as only about 300 people still speak it.

Matambú or Chorotega People: Guanacaste

The Matambú, also called the Chorotega, live in Guanacaste. Their name, Chorotega, means "The Fleeing People." They moved to Costa Rica around 500 AD to escape slavery in Southern Mexico. They are related to the Maya people. Some parts of their ancient Mexican culture, like certain rituals, can still be seen in their history. They were known as a very powerful group during the Spanish conquest. They had an organized military and fought against the Spanish. It is believed they had a democracy and elected Caciques (leaders or priests). They were also a hierarchical group, meaning they had different levels of society. Today, they are known for their farming, especially growing corn, and for their beautiful ceramics and pottery.

Térraba or Teribe People: Southern Costa Rica

There are about 3,305 Térraba people. In 2007, the poverty rate in their region was very high, around 19.3%, compared to 3.3% for the whole country. This is because their forest land, which they used for farming and their economy, has been cleared over the years. They have not kept their language as much; mainly only the elders speak it. However, a larger group of Teribe people live in Panama and still use the language, and the two groups stay in touch.

Current Challenges for Indigenous Communities

Education

Indigenous teachers and students often face challenges in getting the same opportunities as non-indigenous people. For example, in the Boruca and Teribe areas, qualified indigenous teachers were not given jobs in local schools. Also, schools that indigenous students attend often do not get enough funding. This means students might not have the same learning resources. Indigenous people are also working to gain better qualifications from universities so they can get higher-paying jobs.

Land Issues

Costa Rica has about 50,900 square kilometers of land. About 3,344 square kilometers, or 5.9% of the land, is set aside as indigenous territories. The biggest problems for indigenous groups in Costa Rica today are often related to land. Farmers and ranchers in these areas might not fully control their own land because it is part of a reserve. Also, their land is sometimes at risk because of mining and oil projects.

Indigenous peoples are against the current El Diquís Hydroelectric Project. This project would flood some of their lands and affect many groups. It would impact seven indigenous territories, including the Bribri, Cabécar, Teribe, and Brunka. This would be the largest hydroelectric dam in Central America. It would also cut through nearly 200 historical sites and sacred grounds.

Healthcare

Indigenous peoples in Costa Rica often do not get good healthcare services. This is because their communities are in hard-to-reach places, especially in the mountains. Only about 26% of the indigenous population has access to clean water. Because of this, indigenous peoples often rely on their traditional healing practices. Groups like CONAI (National Commission for Indigenous Affairs) have tried to combine traditional and modern medicine. However, this has not been very successful, and traditional ways have not always been respected. Some areas now have clinics, but doctors are often only available a couple of days a week.

See also

In Spanish: Pueblos indígenas de Costa Rica para niños

In Spanish: Pueblos indígenas de Costa Rica para niños

- Chibchan languages

- Pre-Columbian history of Costa Rica

- Intermediate Area

- Mesoamerica

- Isthmo-Colombian Area

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |